A recurrent theme in Knot of Stone is the quest for an esoteric school of thought—sometimes known as Grail Christianity or Rosicrucianism—that survived suppression by Catholic Rome and which helped unite centres of independent learning in Europe and Africa. Our East meets West post also touches on the idea that Jerusalem, and not Rome, once served as the historical link between East and West.

The African Century

For over one hundred years a restless Portuguese nation led Europe’s expansion into Africa. This era began with the capture of Moorish Ceuta in 1415, then the “key to the Mediterranean”, and drew to a close with the untimely death of Francisco d’Almeida in 1510. Almost a century apart, these two defining events occurred at opposite ends of the continent and illustrate a period of bold, brutal and bloody conquests under the influence of Mars, the Roman god of war.

In a war waged against the Arabs and the Turks—from the river plains around Lisbon to the walls of Jerusalem—Portugal’s best ally was thought to be that of Prester John, or Preste João, a priest-king who’s legendary realm lay somewhere south of the Sahara, that is, beyond the source of the Nile. Cut off from the rest of the world, his Lost Kingdom contained the oldest blend of Christianity known outside Europe. Here too, or so Christians believed, a pure and unspoilt faith still existed. As modern neo-Templar knights, Prince Henry’s navigators sailed in hope of finding this faith on the far-side of East Africa. And so a legend became history.

“Below the belt of Islam, Henry had predicted, an alliance with Prester John would reunite East and West.” KoS p.165

The Legend and the Letter

The Legend and the Letter

Much of the legend surrounding Prester John appeared in the late twelfth century when knightly orders and chivalrous virtues were at their height and Rome over-reached itself. This was largely due to a letter purportedly written by Prester John and addressed to Emperor Maximilian, dated 1165, which circulated throughout the Holy Roman Empire. For whatever reason, be it fantasy or escapism, the story inspired adventurers, explorers and scholars. They all hoped to find the realm of Prester John and thus, during the next two centuries, such stories were fervently recorded all over Europe. With the invention of the printing press in the 1440s, the letter became Europe’s first best-seller and appeared with ever more embellishments in the centuries to follow. (KoS pp.180–183)

Prince Henry the Navigator

Portugal’s Prince Henry was quick to recognise that an alliance with Prester John could reunite East and West, both militarily and spiritually, while furthering the exchange of knowledge from diverse corners of the world. As part of a courageous three-pronged approach, his successor João II tried reaching Prester John via the Congo River. It was at Portugal’s trade depot in Benin, today Nigeria, that the explorers first came to hear of an emperor who inaugurated his lords by bestowing on them a helmet, a sceptre and a cross—all symbols of a Christian priest-king—and yet no local ever claimed to have seen him. Emperor Ogané, they said, was always screened by colourful silks, patterned bark-cloth, and presented only a foot during an audience. While such fabulous stories served to rekindle the legend, explorer Diago Cão sailed up the Zaïre River in search of the Black Potentate within the Old Kingdom of Kongo, now northern Angola. On reaching the Yellala cataract 180kms upstream, his captains chiseled their names into the rockface and continued on foot.

Determined to succeed, Cão’s men persisted overland by dragging their longboats behind them, until it dawned on them that this Black Potentate was not the same as the one of Christian legend. (KoS p.96) Be that as it may, the East was not to be found by transversing the continent—a fact White explorers would only discover centuries later.

Since Ptolemy claimed that the Terrestrial Paradise lay below the branches of the Nile, medieval scholars were quick to assume it included Prester John’s realm and that this was accessible from East Africa’s Barbaria Coast. The old trade route started out from Massawa and Mombasa but, in time, shifted to Zanzibar and Sofala. Most coastal towns were under Muslim control—an alarming prospect for Christians still fighting an African Crusade in the 15thC.

Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias

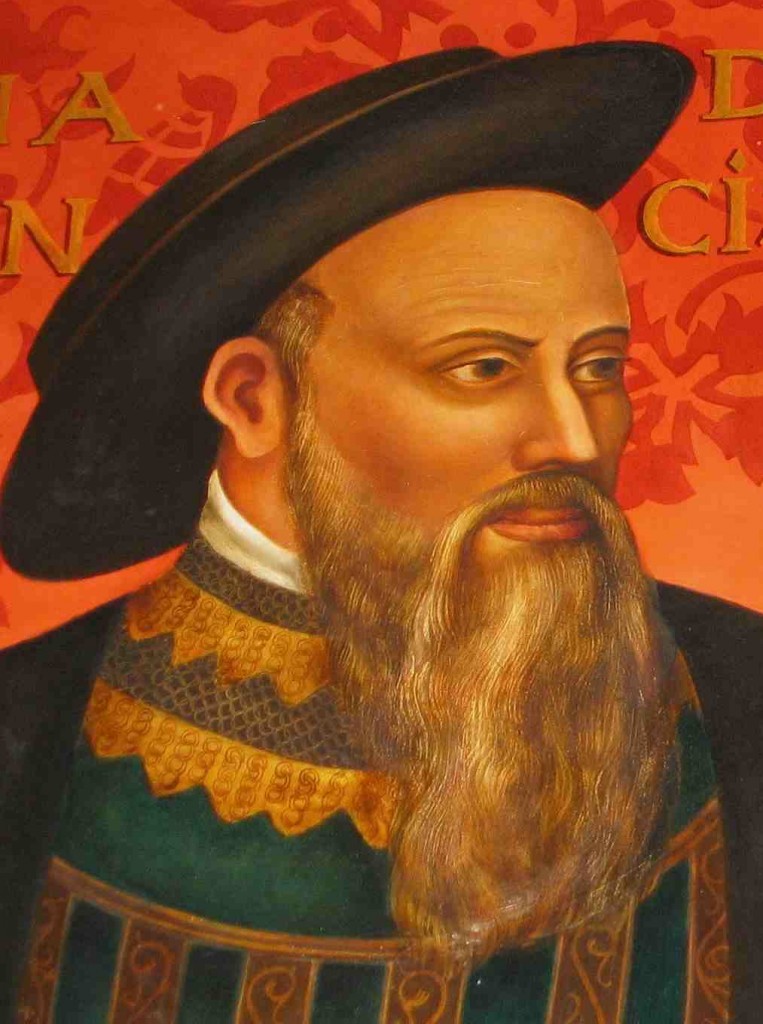

To this end Bartolomeu Dias sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in search of the Presbyter’s realm, then thought to be somewhere in the Indies, that is, on or around the Indian Ocean rim. In the year that Dias left, 1487, his compatriot Pedro da Covilhã also set off to find Prester John’s realm. While Dias opened up a new route in the Atlantic, Covilhã travelled via the age-old caravan routes across the Sahara. Years later, long after Dias had returned, Covilhã reached the court of Emperor Eskender in Yeha, near Aksum, in Ethiopia, whereupon he was detained for the next thirty years: never to see his wife in Lisbon again, nor the child she was carrying thirty years before. Together Dias and Covilhã made the most important joint-venture in the history of pioneer exploration. It was also the year in which the Cape of Good Hope became entangled with the quest for Prester John. (KoS p.79, 133, pp.156–157) Or, to put it differently, the Cape was discovered on the way to find Prester John. (KoS p.188)

The stone-carved Church of St George (Bete Giyorgis) in Lalibela, Ethiopia, also known as an “Eighth Wonder of the World”. According to some scholars the church bears the Templar cross on its roof. (KoS p.189) Photograph by Paolo Pagni. Watch his video ‘Ethiopia: Nelle Case di Cristo’. Courtesy of www.reporterlive.it

The stone-carved Church of St George (Bete Giyorgis) in Lalibela, Ethiopia, also known as an “Eighth Wonder of the World”. According to some scholars the church bears the Templar cross on its roof. (KoS p.189) Photograph by Paolo Pagni. Watch his video ‘Ethiopia: Nelle Case di Cristo’. Courtesy of www.reporterlive.it

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama

A mere decade later, when Vasco da Gama sailed for India in 1497, the dream of Prester John’s Terrestrial Paradise had been overun by the desire for material wealth: for the silks, spices and jewels of the Orient. It was in Mozambique (Moçobiquy) that Gama heard about Prester John and the coastal towns of White Christians who had fought the Moors. These were probably descendants of former Chinese seafarers or local Hindu traders.

The stories surrounding the fabulous figure of Prester John are linked to the legends of Parsifal and King Arthur; to the quest for the Holy Grail and its Lost Paradise. According to Wolfram von Eschenbach, the Grail’s final resting place was in the East where Prester John served as its last guardian. Not only was he the Last Guardian of the Grail, but both he and the cup were to be found in Africa. In short, Prester John became for Africa what King Arthur has been for Britain. (KoS pp.185-6)

Francisco d’Almeida

Francisco d’Almeida

Francisco d’Almeida was among the last of his generation—described by Camões as the “Marvellous Generation”—who strove to unite East with West, cosmopolitan societies with universal values. Sadly, after Almeida’s death the Templar ideal of a singular, unified spirituality also died. To this end, the story behind Knot of Stone endeavours to renew this impulse, as demonstrated by this startling revelation concerning Preste João:

“The Realm of Prester John was an esoteric legend or device designed to manage schismatic Christianity and the renewed drive toward a unified age of spirituality during the medieval Crusades—setting a precedent for the European Renaissance. At the epicentre was the Rosicrucian flame of Gnosis burning in the lamp of Nestorian Christianity in the Eastern world, a flame seeking to transmit itself westward again. For several centuries the esoteric Orders used the legend of Prester John as a ploy to influence the turn of historic events—especially the political interplay between East and West—and to maintain a balance of power conducive for the cosmopolitan culture of the Renaissance with its hybrid philosophy, art and spirituality. Ultimately, Prester John represented the elusive Platonic ideal of the philosopher-king held by the Christian world as the representative of a kingdom to be sought within, firstly, before it could be realised outwardly.”

Clairaudient message cited in KOS p.188

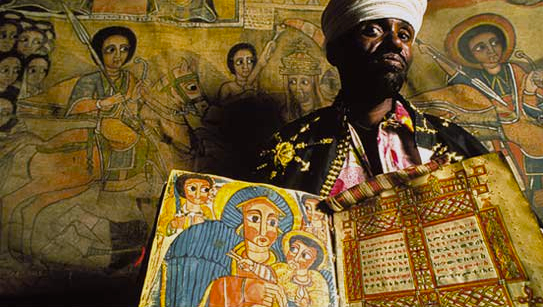

‘Keepers of the Faith’ cover, a photographic tribute to Ethiopia by Paola Viesi, c.2011. Courtesy of the Artist.

‘Keepers of the Faith’ cover, a photographic tribute to Ethiopia by Paola Viesi, c.2011. Courtesy of the Artist.

Nicolaas Vergunst