The location of South Africa’s first recorded battle and earliest known war memorial was lost to history for five centuries. Already in 1512, a mere two years after the event, returning sailors were unable to identify the site. Thus, while researching Knot of Stone between 2004–2009, I could only imagine the setting: a disused railway yard where old tracks traced the former curve of Table Bay. Then, in 2012, the site was ‘rediscovered’ and found to resemble the book’s original description with uncanny accuracy. Today, sadly, the location remains an unfitting memorial for the dead.

Knot of Stone begins with the discovery of a centuries-old skeleton in an abandoned shunting yard which was imagined as follows: “Prof Mendle set off, Sonja by his side, between piles of sleepers and tracks choked with weeds. He led her past a disused warehouse with its derelict loading bay, and then on beyond a platform strewn with splintered packing crates and old pallets. Everything was broken, barricaded and abandoned…”. (KoS p.8)

Knot of Stone begins with the discovery of a centuries-old skeleton in an abandoned shunting yard which was imagined as follows: “Prof Mendle set off, Sonja by his side, between piles of sleepers and tracks choked with weeds. He led her past a disused warehouse with its derelict loading bay, and then on beyond a platform strewn with splintered packing crates and old pallets. Everything was broken, barricaded and abandoned…”. (KoS p.8)

A new discovery?

To commemorate the anniversary of Almeida’s death in 2012, I accompanied Dr Stewart Young, a polymath and gifted dowser, to an undisclosed site beyond the Castle of Good Hope—a site farther east of what I’d previously considered possible—until he halted me and then intuitively said: “We should be able to see where Almeida was killed from here”. However, barred by locks, chains and a razor-wire wall, we were unable to enter the industrial shed which, or so my companion alleged, covers the spot where Almeida lies buried. The following day, with permission to wander around, I discovered how well the location fits the historical record, including its proximity to the Liesbeeck/Salt River Canal, and that this ‘discovery’ could reveal the first recorded battle site and earliest known war memorial in South Africa’s history.

These two maps portray the changing curve of Table Bay as seen, firstly, two hundred and fifty years ago and, secondly, as it appears today. The first reveals the natural shoreline, the latter the land reclamation project of the intervening centuries. In both maps the Castle of Good Hope—here a star—establishes a fixed point of reference while the arrows point to the vicinity of Almeida’s death. The first arrow points to the area described in Knot of Stone, the second to a site since identified by Dr Young. In physical terms the two sites—or arrows—are about four kilometres apart and, like the Castle itself, lie a kilometre inland today.

These two maps portray the changing curve of Table Bay as seen, firstly, two hundred and fifty years ago and, secondly, as it appears today. The first reveals the natural shoreline, the latter the land reclamation project of the intervening centuries. In both maps the Castle of Good Hope—here a star—establishes a fixed point of reference while the arrows point to the vicinity of Almeida’s death. The first arrow points to the area described in Knot of Stone, the second to a site since identified by Dr Young. In physical terms the two sites—or arrows—are about four kilometres apart and, like the Castle itself, lie a kilometre inland today.

Physical location

Physical location

In a windswept wasteland between Table Mountain and the sea, near the Liesbeeck-Salt River Canal, lie the forgotten bones of Almeida and his sixty compatriots. The spot where they fell lies under a derelict railway yard—beneath a low, red bricked shed—surrounded by rusting wagons, old splintered crates and wooden pallets. Laid to rest five centuries ago, their bones have been lost to memory and long overlooked by subsequent historians. Drawing on the popular memory of his contemporaries, the poet laureate Camões wrote:

The Stormy Cape which keeps his memory Along with his bones, will be unashamed In dispatching from the world such a soul Neither Egypt nor all India could control. Camões, Lusíads, 1572.

The Stormy Cape which keeps his memory Along with his bones, will be unashamed In dispatching from the world such a soul Neither Egypt nor all India could control. Camões, Lusíads, 1572.

Luís de Camões’s epic poem predicts that the Cape of Storms (Cabo Tormentoso) will preserve both Almeida’s memory and his bones. At that time, the Cape was seen as a Portal to the Indies: a threshold between the cold Atlantic and a warm Indian, and as “earth’s extremest end”. A century later, in 1652, under another flag, the Cape became the furthest south of all Holland’s colonies.  Almeida’s bones thus rest at a cornerstone of colonial history.

Almeida’s bones thus rest at a cornerstone of colonial history.

Historical context

Hearing about the death in Lisbon, King Manuel announced a day of mourning and forbade his ships from calling at the Cape, again, unless in dire necessity, and thereby prevented Almeida’s bones from returning to Portugal. King Manuel was superstitious, believing the fallen sons of Lusus (Portugal) protected his realm and, allegedly, added: “as long as his bones are there, all is safe”.

“While Almeida’s bones lie at the Cape, all is safe.” Manuel I, 1510.

At the time, Manuel I (shown directly above) ruled over the first global empire and was then one of the most powerful men in the world. His decision against further landings along the Cape coast would ultimately delay European occupation for another 142 years.

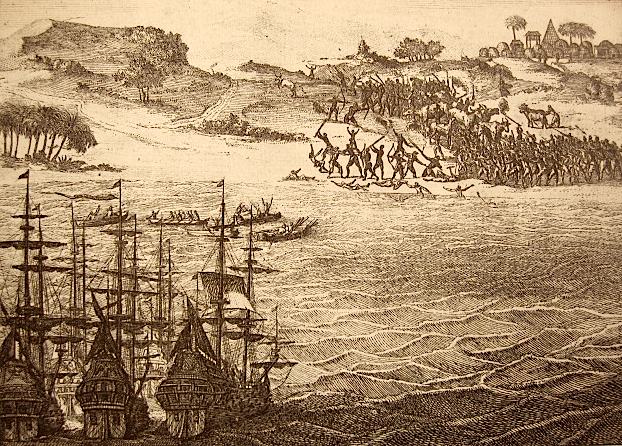

The attack on Francisco d’Almeida at the Cape of Good Hope, 1510. From Pieter van der Aa’s Naauwkeurige verzameling der gedenkwaardigste zee- en landreysen naar Oost- en West-Indië, Leiden, 1707.

The attack on Francisco d’Almeida at the Cape of Good Hope, 1510. From Pieter van der Aa’s Naauwkeurige verzameling der gedenkwaardigste zee- en landreysen naar Oost- en West-Indië, Leiden, 1707.

In 1512, two years after Almeida’s murder, a passing Portuguese ship touched at the Cape to collect fresh water. On board was the former master of Almeida’s boat and a relative of one of the deceased, Cristóvão de Brito, who asked to be taken ashore to see the grave. On finding the site “without a sign of those who lay there”, Brito had a wooden cross and cairn of stones erected to mark the spot. This ensemble became the first memorial built by white interlopers in South Africa.

Early illustrations

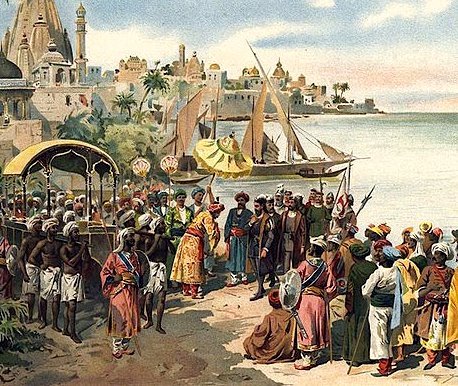

The only historical illustrations of Almeida’s murder—and of Brito’s subsequent visit—were made two centuries after the event, in 1707. These were published by Pieter van der Aa, a renown cartographer and printer from Leiden, Holland, in his collection of notable land and sea travels to the East. Printed as fold-out folios, the engravings were often removed by collectors and so not easily recognised or identified by later historians. The scene showing several seamen erecting a cross was only ‘rediscovered’ by Cape Archivist, Victor de Kock, in 1952.

Erecting a cross to mark the grave of Francisco d’Almeida, 1512. From Pieter van der Aa’s Naauwkeurige verzameling der gedenkwaardigste zee- en landreysen naar Oost- en West-Indië, Leiden, 1707.

Erecting a cross to mark the grave of Francisco d’Almeida, 1512. From Pieter van der Aa’s Naauwkeurige verzameling der gedenkwaardigste zee- en landreysen naar Oost- en West-Indië, Leiden, 1707.

Postmortem

In traditional African societies—unlike western Christendom—the bones of the ancestors are seen as sacred and kept close to the family hearth. As such, ancestral graves are integral to a healthy domestic-social life and the bones important for settling disputes, putting the deceased to rest, and for predicting the future. Bones are also used to call up the Ancestors, like witnesses to a trial, in order to see justice served. Seen in this context, Almeida had to die at the Cape of Torments.

At Almeida’s posthumous trial—that is, speaking metaphorically—the Ancestors came from the far-off shores of Kenya and Tanzania. And to this Camões adds that Almeida was killed for the plundering of Kilwa and Mombasa in 1505, five years earlier, on his outbound voyage, when his men brutally butchered the local Swahili and Arabs. His death was a retribution.

At Almeida’s posthumous trial—that is, speaking metaphorically—the Ancestors came from the far-off shores of Kenya and Tanzania. And to this Camões adds that Almeida was killed for the plundering of Kilwa and Mombasa in 1505, five years earlier, on his outbound voyage, when his men brutally butchered the local Swahili and Arabs. His death was a retribution.

Cape Town’s history is thus as much part of East Africa as it is a part of South Asia: the geo-politics of each overlap. More so, Egypt and India had a knock-on effect all the way down the coast—from Melinde to Mombasa, from Kilwa to Sofala—ending at the Cape of Good Hope. And Almeida’s murder demonstrates this.

Cape Town’s history is thus as much part of East Africa as it is a part of South Asia: the geo-politics of each overlap. More so, Egypt and India had a knock-on effect all the way down the coast—from Melinde to Mombasa, from Kilwa to Sofala—ending at the Cape of Good Hope. And Almeida’s murder demonstrates this.

While the site may never be excavated nor his bones ever found, the ‘discovery’ raises a telling question: To whom do his bones belong? To his family, to his country, or to his old fraternity?

African Sacred Ibises over Cape Town’s forgotten shoreline, an alternative view of Table Mountain, 2011. Photograph courtesy of Mike Golby.

African Sacred Ibises over Cape Town’s forgotten shoreline, an alternative view of Table Mountain, 2011. Photograph courtesy of Mike Golby.

Future Developments

Cape Town’s proposed regeneration programme for the Voortrekker Road Corridor and “Salt Rivièra” renewal project will, I hope, include a new memorial for all the victims and descendants of the Almeida/Khoena conflict. There is currently no other memorial in South Africa or Portugal and, as far as I know, none were ever erected to commemorate this tragedy. Not one in five hundred years? Well, perhaps it is time to let Hope grow out of Torment as the Cape outgrows its Storms.

Bird’s eye view of the battle-burial site (encircled) and its proximity to the Salt River Canal, Voortrekker Road and Ysterplaat Station. The proposed urban and recreational development project, if successful, could offer unparalleled opportunities for the identification, excavation and commemoration of this long-lost battlefield, its graves and original stone cairn memorial.

Bird’s eye view of the battle-burial site (encircled) and its proximity to the Salt River Canal, Voortrekker Road and Ysterplaat Station. The proposed urban and recreational development project, if successful, could offer unparalleled opportunities for the identification, excavation and commemoration of this long-lost battlefield, its graves and original stone cairn memorial.

Part Two of this post continues here.

Nicolaas Vergunst

All this makes for a fascinating read and it’s just as well I published my own book Assegais, Drums and Dragoons before seeing this, or I might have wandered seriously off-subject!

Whatever the deeper causes, I stand by what I wrote about the fight: that Kwena headman knew his onions. The most significant aspect, of course, is that it led to the Portuguese shunning the Cape (which in my opinion was a good thing for the locals, given the unfortunate Portuguese predilection for slaving) and therefore led to a totally different history for all of South Africa and far beyond.

I think that I also managed to put one important fact in perspective: a unique military combat mindset developed at the Cape as a result of a blending of orthodox European doctrine and the local concept of high mobility and veldcraft; the final element which brought all this together was Jan van Riebeeck’s introduction of horses, the ultimate mobility requirement. That mindset exists to this day—all that has changed are the vehicles and weapons. In some ways the same sort of blending (conscious or unconscious, obvious or invisible) took place on the social history side as well, so that the Cape was well on its way to developing a unique society by the end of the 18th Century.

It’s sad that we spend so much time arguing about the iniquities and otherwise of the past when, instead, we should remember that what we have in common as a community is far greater than that which divides us.

Thanks for the valuable contribution, Willem, and for your remarks on early combat tactics at the Cape. My main character (or “focaliser”) is a Dutch historian and keen equestrian, Sonja Haas, who I’m sure would love your reference to Van Riebeeck’s horses!

The fact that the Portuguese shunned the Cape of Good Hope is a matter already mentioned on my blog below. As the full title of Knot of Stone proposes, this was a day that changed South Africa’s history since, were it not for this event, the entire sub-continent from the mouth of the Congo River to the Mozambique Channel may well have fallen to the Portuguese for the next four hundred and fifty years. That is, until the 1970s, making of southern Africa a second Brazil, potentially? Although my book deals with this thematically, and then only in brief, you may find it convenient to start with my synopsis below: Why South Africa isn’t Brazil.

As to your lovely closing comment, I couldn’t agree more. The ties which bind us to the Cape are far greater than those that divide us.

Thanks for pointing that out—if only people could see history for what it was an not by who it was told.

Interesting!

Fascinating history.

Thanks for including my photograph of the ibises above. For what it’s worth, I’ve always been drawn to that particular patch of land. I don’t know how many others have felt compelled to go down there to try capture what feels to be an eternal graveyard. This was taken two years ago at the entrance to the yards on the Cape Town side of the river, pretty close to where you locate the site of Almeida’s death. The birds? Go figure. Wikipedia tells us:

‘There is a region in Arabia where I saw the bones and spines of winged serpents in such great quantities that it is impossible to report on the number. There were heaps of spines, some heaps large and others less large and others smaller still than these, and these heaps were many in number.

‘The spines are scattered upon a great plain that adjoins the plain of Egypt. Here, at the beginning of each spring, the winged serpents are met by birds called ibises which fly out to kill them. On account of this, say the Arabians, the ibis is greatly honoured by the Egyptians.’

Source: Wikipedia http://tinyurl.com/q5xna3y

Thanks for your evocative photograph of Cape Town’s “eternal graveyard” and the reference to the African Sacred Ibis. Your evocation of the ibis as both protector and slayer is most apposite since, curiously, it echoes how sixteenth-century Portuguese chroniclers described Almeida’s assailants, namely: “they appeared as birds, or rather, like the devil’s executioners”. (KoS p.46)

Your photo also captures the scene vividly described by Herodotus when he says that the bones were heaped together, some in large piles, others small, but too many to be counted. From the dowsing done by Dr Young in situ last year, it appears that there are still countless bones, large and small, buried under that patch of land. So yes, Mike, as you say, go figure!