Patric Tariq Mellet and Nicolaas Vergunst continue their discussion of the Almeida-Khoena conflict and what its diverse interpretations mean for descendants and historians today.

Patric Tariq Mellet: As the ‘Coloured’ or Camissa people we know a few things about ourselves with certainty. We are the children of old indigene societies; we are the descendants of uprooted slaves from Africa, India, Indonesia and China; and we are partly rooted in European and Arab societies. When we look at that part of our ancestry and heritage—from the first interactions between our ancestors to the last forced removals of our families—we have had one indelible and seminal moment to commemorate. This is the Goringhaiqua’s resistance to Almeida’s violation of their trust and their subsequent victory. You may choose to criticize our outlook, but it is a very real cultural and symbolic one in our community—and one that’s very fragile for a long subjugated people.

Our interest is thus not with the Portuguese and their Catholic intrigues back home. Our interest has simply been with the intrusion of Europeans (not only the Portuguese) in Africa and with our ancestors standing up boldly for themselves. This may not seem important to others, but it is of tremendous significance to surviving marginalized indigene groups in Cape Town. The conflict on the beach illustrates that the Khoe people were no pushover. It was our “Custer’s last stand”, gross as this might sound.

Our interest is thus not with the Portuguese and their Catholic intrigues back home. Our interest has simply been with the intrusion of Europeans (not only the Portuguese) in Africa and with our ancestors standing up boldly for themselves. This may not seem important to others, but it is of tremendous significance to surviving marginalized indigene groups in Cape Town. The conflict on the beach illustrates that the Khoe people were no pushover. It was our “Custer’s last stand”, gross as this might sound.

Your version of an assassination plot simply wrests a victory from our annals of history. As much as my version of a victorious battle may be inconvenient to you, so your story of a hidden plot is inconvenient to the version that I subscribe to. An assassination plot in the manner you would have it undermines our anti-colonial resistance story.

Nicolaas Vergunst: Let me interrupt here, please, if only to say that I don’t intend to diminish your finest hour in history; but simply wish to add that Almeida’s assassins took advantage of the situation by ritually piercing him through the throat with a lance of steel. According to my research, and its all at the beginning of Knot of Stone, it would appear that this was done as an order of execution only some time after the Portuguese had been defeated by the Khoena (I use ‘Quena’ in my book). The ceremonial execution, uncovered through corroborative clairaudient and psychic input spanning almost a century, 1924-2012, was done when Almeida already lay dead on the beach.

PTM: What difference does that make? We celebrate this unique event with pride because the most powerful General in Europe was defeated by a small and humble group of African herders. The latter had less sophisticated weaponry, but still outsmarted a man who had been the scourge of the Turks, Egyptians and Indians. Almeida certainly was the most ruthless and powerful military man of his day, with military history projecting him as undefeatable in his successive attacks of coastal towns in East Africa and West India. He was to Africa and India the Attila the Hun of his time.

NV: In fact, Almeida was denigrated by his contemporaries for his lack of aggression! His rival and successor, Afonso de Albuquerque, was hailed as The Terrible, Caesar of the East, Lion of the Seas and as The Portuguese Mars. He made Almeida look pathetic; calling him a coward and saying he lacked boldness, all because Almeida didn’t sack more port-cities under Muslim control. I also suspect Albuquerque had a hand in the assassination plot, but that’s in my book too, as is the historical Attila the Hun, so let’s not spoil the fun for our readers now. Instead, you were just saying something about military history?

NV: In fact, Almeida was denigrated by his contemporaries for his lack of aggression! His rival and successor, Afonso de Albuquerque, was hailed as The Terrible, Caesar of the East, Lion of the Seas and as The Portuguese Mars. He made Almeida look pathetic; calling him a coward and saying he lacked boldness, all because Almeida didn’t sack more port-cities under Muslim control. I also suspect Albuquerque had a hand in the assassination plot, but that’s in my book too, as is the historical Attila the Hun, so let’s not spoil the fun for our readers now. Instead, you were just saying something about military history?

PTM: Military historians evaluating this battle recognised the application of the Goringhaiqua battle leadership style—what’s now called the principles of war—which included their use of spearmen in infantry style together with oxen in modern armour style. This together with fighting at a time and place of their choosing, avoiding the beach, maintaining the element of surprise, utilising familiar terrain, attacking with maximum violence and speed, and not disengaging but keeping up the momentum of the attack, all combined to bring about Almeida’s defeat. In the words of one military historian, Almeida was “out generalled”.

NV: Ah, that’s quotable, as too your expert military analysis. So who’s this historical authority?

PTM: Spar nicely, lol. Willem Steenkamp, military historian and well-known military commentator who evaluates the conflict involving the Almeida and the Khoena in his book Assegais, Drums and Dragoons (2012). His book was launched in Cape Town last week. We stand in opposite trenches and have many differences of opinion on this matter.

From what I can gather in your version, the Goringhaiqua were incidental bystanders and simply used as a diversion for the assassination of Almeida, in fulfillment of a prophecy? If so, Africans are once again stripped of being determiners of their own history. The European plot replaces the local narrative in favour of an unfolding struggle between different European forces. In one fell swoop we are robbed of an important point of reference in our anti-colonial resistance… one of the few handed down to us by European historians and, dare I say it again, the only one in which our forebears were victorious!

NV: We needn’t labour the point here: the Goringhaiqua thwarted the Portuguese, yes. They were neither bystanders nor extras in a scheme of diversion. I’d like to emphasize that I now believe the conspirators set up the ambush, quite unbeknown to the villagers, and made sure Almeida’s retreat would be cut off and that he and his loyal followers would be left exposed on the beach.

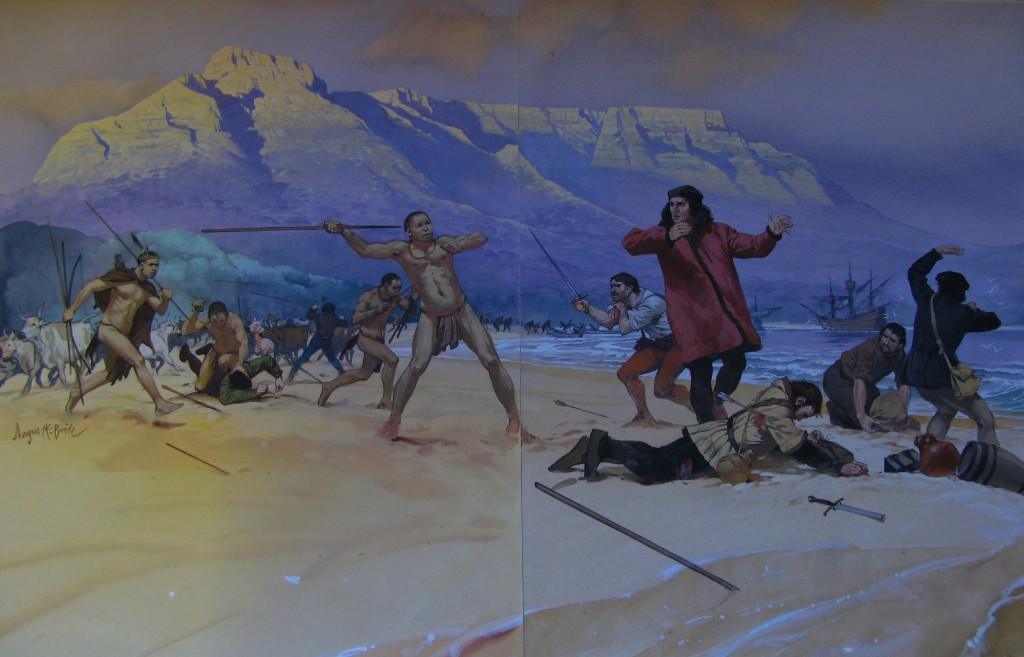

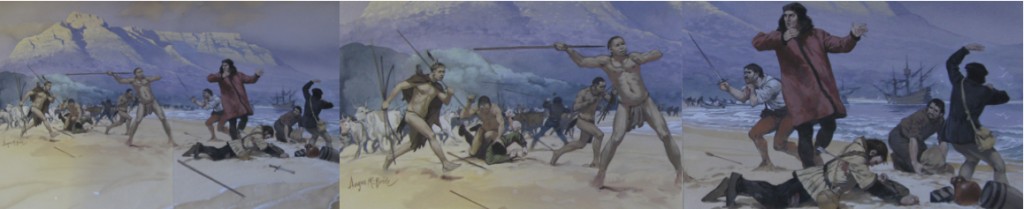

The massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida in 1510 by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy of the Castle Military Museum. Curiously, the artist depicts the battlescene with consistent accuracy, not only in its location, but in showing how some men abandoned Almeida and fled down the beach to where the longboats awaited them.

The massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida in 1510 by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy of the Castle Military Museum. Curiously, the artist depicts the battlescene with consistent accuracy, not only in its location, but in showing how some men abandoned Almeida and fled down the beach to where the longboats awaited them.

PTM: It could certainly have been a natural progression of events that led to the final battle providing a perfect opportunity being made available to possible conspirators. A perfect storm, so as to say, where conspirators deviously arranged events to provoke an angry and full-scale retaliatory attack by the Khoe.

NV: Yes, that’s how I think it probably happened.

PTM: Well, I work in the Maritime environment and come from a seamanship family, so I know about the mischief caused by crew going ashore each time a ship enters port. However, such antics seldom involve the skippers or, as in this case, the admiralty and senior officers. And yet Almeida and eleven of his captains did just that—and were all killed? I just can’t see why he’d send such a large party ashore, let alone go so far inland himself? After all, there was nothing substantial to gain. This fact stands out as highly unusual and should perk up the detective in anyone. What spurred this party to go ashore? What prompted such an auspicious war party to go head to head with a people they regarded as primitive and inferior?

NV: I couldn’t have said it better myself, Patric. Yes, indeed, why did Almeida go ashore? And what did he personally need to do at the village? Remember, it lay a few hours walk from the shore and his men marched there before dawn. Some accounts say they set off one hour after midnight, and that Almeida was taken by longboat to the mouth of the inlet or lagoon, halving the distance the others had to walk. But then he was sixty years old, and not in good health. Anyway, for me one important question remains unanswered: was it really a punitive expedition, a war party?

PTM: All the records point to it being so.

NV: I know, but is it possible that Almeida stepped ashore to honour the Goringhaiqua leader with some proposal or league that had been envisaged for both their futures—or one that the Chief himself had requested? As you yourself say, the Goringhaiqua were hospitable and friendly by nature. Whatever scenario is considered, it must inescapably include some realistic reason for Almeida to feel the need to present himself in person, where even a second-in-command would not suffice. It was surely in Almeida’s interests to ensure that the next fleet would be well received when the Portuguese returned to barter. As you also know, a mariner’s survival depends on clean water and fresh produce to eat during a long voyage at sea. For any lesser reason, Almeida’s second-in-command would surely have been able to deal with the matter alone?

PTM: I’m not so sure about this, because the details provided in the different Portuguese versions don’t give us any lead in such a scenario. Even if Almeida was enticed to go ashore to support a punitive party, or whatever you wish to call it, it seems foolish of him not to have remained safely behind his own lines. Inexplicably too is the report that the longboats were pulled back beyond the breakers, rather than drawn onshore as was standard practice. The reasons given, citing foul weather and rising tide, are questionable. There is also no record of any deterrent canon fire from the ships. So I guess a simple twist of fate could, quite plausibly, have presented an opportune moment for a clever bit of manipulation when a retreat needed to be organized hastily.

NV: To my mind, the men who ran ahead of Almeida pre-empted the battle by attacking the village: ransacking huts, capturing hostages and driving off what cattle they could rustle. In the ensuing chaos one of the men killed his compatriot, Fernaõ Lanças. When news of this travesty reached Almeida, then still on his way, he called off the expedition and began to withdraw to the beach. These men—called “the ever bellicose fidalgoes” or quarrelsome minors elsewhere—created enough confusion to ensure that Almeida could be ambushed on his return without their strategy being detected. For the Goringhaiqua, as you say, they simply defended themselves against this treacherous betrayal and, understandably, retaliated by driving their cattle against the heels of their foe.

PTM: But the real battle awaited the Portuguese on Woodstock beach itself, near the mouth of the Salt River.

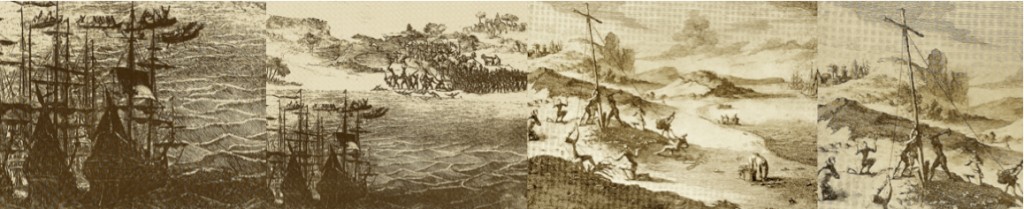

The old Salt River estuary looking towards Woodstock, with a cloud covered Table Mountain. Date unknown.

The old Salt River estuary looking towards Woodstock, with a cloud covered Table Mountain. Date unknown.

NV: Yes, though there seems to be some difference of opinion on the exact location. This is partly due to the convergence of the Salt, Liesbeeck, Black and Diep river system into a common lagoon with a shared mouth. Furthermore, perennial tides and storms caused the sandbars and estuaries to shift seasonally, as shown in early maps. Despite the lack of detail in contemporary Portuguese records, we all agree that Almeida’s last stand was on a beach: a beach hemmed in between sand dunes, a river mouth, and the rising summer tide.

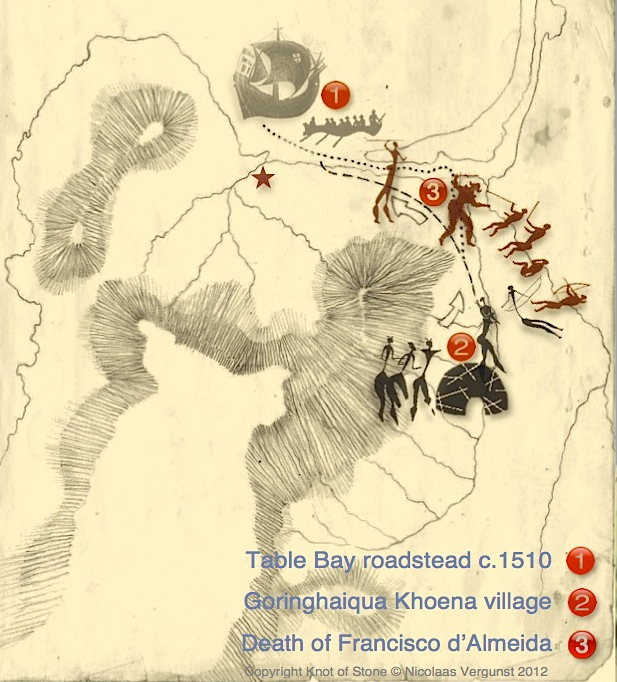

Reconstruction of the Salt River estuary (3) and the wetland/beach where Almeida was killed.

Reconstruction of the Salt River estuary (3) and the wetland/beach where Almeida was killed.

Two swords mark the presumed battle site on the left bank of the Liesbeeck-Salt River Canal.

Two swords mark the presumed battle site on the left bank of the Liesbeeck-Salt River Canal.

PTM: In my opinion, the key to your version is the opportunity that arose in subtly manipulating events during the retreat. Anything more obvious would have had severe ramifications back home.

NV: Right. The instigators had to ensure their chances of getting away, back to the boats, and that no surviving compatriot should suspect any conspiracy. I believe it was for this reason that the survivors elected Jorge Barreto and not Almeida’s obvious successor, Jorge de Mello Pereira, to report on the event back in Lisbon.

Although my book describes how a metal spear was driven through Almeida’s throat—that is, after his death, when the Portuguese returned to bury their dead that same afternoon—this does in no way detract from the fact that he had been killed in the skirmish by a wooden spear which pierced his neck from the back, and protruded out in font. Almeida tried to pull it out, apparently, but collapsed before he could do so. It seems he died almost immediately. Having said this, I feel my scenario neither undermines the fortitude of your Khoena ancestors, nor detracts from their bravery and evident military skills.

PTM: I believe that nothing in the your plot changes the situation as seen by the indigenes or their descendants. With or without your so-called ritual assassination, even afterwards, the Goringhaiqua still come out tops that day.

NV: While Greg Dening says history was born on the beaches, on those marginal spaces between land and sea, our first footprints have long since disappeared with the rising tide of colonial history in South Africa. For this reason I believe, like you Patric, that we should tread carefully when retracing our early footsteps—or we may trample over the last prints left on our beaches. As I say in Knot of Stone, there’s no intertidal space where Africa’s past and Europe’s history do not intersect, no beach below Table Mountain where the footprints of both native and interloper haven’t overlapped, and no reconstruction of Almeida’s murder from which either party can now escape. It’s one event that binds us together.

PTM: Yes, I agree, it’s an event with hidden ties that bind us historically, but for those of us trying to find positive moments around which we can reconstruct a sense of who we are as ‘Coloured’ or Camissa people, free of any past overlays, it is one event that we want to rewrite ourselves.

This concludes the second part of our online discussion. Patric Mellet is the author of ‘Lenses on Cape Identities: exploring roots in South Africa’ and writes a regular blog for Cape Slavery Heritage. My warm thanks to him for his temperate participation.

Nicolaas Vergunst

UCT Press passed on your kind email following the launch of Imagining the Cape Colony in Cape Town last week. Thanks for your generous thoughts.

Regarding the choice for my cover, I selected it from your splendid catalogue of the Hoerikwaggo exhibition at the SA National Gallery. I am fascinated to see in your email that the original coloured engraving is from c.1750. If possible, I’ll have this added on subsequent editions of my book (Edinburgh University Press are planning a paperback edition soon).

I see you have a new book out on Almeida’s demise (the subject of my own first chapter). Like you, I am sorry we never met to exchange ideas before finishing our work. I’ll buy yours this week. Again, thank you indeed for making contact.

Curiously, those writing about the Cape are often doing so from afar, working on their texts at a distance. As you also know, Alan Paton’s memorable first lines to Cry, the Beloved Country were written in a hotel room in Norway. While I generally avoid clichés, ‘absence makes the heart fonder’. So does modern travel and online communication, putting us virtually in two-or-more places at the same time. Such is the world we live in, as too the perspectives we’ve written about in our books. Unlike you, I have no museum or university network, no institutional base, no senior common room in which to test ideas, and no day-to-day contact with sparring partners. So I regret not having known about your book earlier.

In fact, I only became aware of your research during my online debate with Patric Mellet, above, and have since ordered a copy of Imagining the Cape Colony.

I look forward to reading your first chapter and suggest that we all get together, somewhere, sometime, if only to exchange hotel pens or sign each others’ books.

I’m interested in what your book has to say about the actual King Attila, or as you choose to call him, ‘Attila the Hun’. Coming from a culture where Attila is a hero—and not the savage or barbarian the West paints him as—I’d be most interested to see how you have portrayed him. I’ve just read Willem Steenkamp’s Assegais, Drums and Dragoons and would love to be better informed about the military history of the Khoina (Khoena, Kwena, Qwena) people.

Thanks for your interest, Chris, I see you are a freelance military journalist living in South Africa. Given your allusion to the 1806 British occupation of the Cape as a forgotten episode in the Napoleonic Wars of Europe, Digital Journal (6 June 2012), I’ll use Napoleon himself as my point of departure to your question above. Knot of Stone has two references to Attila that may interest you:

The first comes from Credo Mutwa—the much-maligned Zulu sanusi or shaman—who once observed that Attila the Hun, Julius Caesar, Napoleon and Hitler, even his compatriot Shaka Zulu, all died miserable lonely deaths. See KoS p.78

The second reference—also from a healer empowered by the Ancestors—likens Attila to Napoleon and suggests that both soldiers were cut from the same cloth or, rather, forged by the same fire. As two of history’s greatest military leaders, Attila and Napoleon almost conquered all Europe using the same routes, while marching in contrary directions. Attila is similarly compared to Genghis Khan, for which both are remembered as being short with a broad chest and large head. They share the same title as Napoleon, karmically, claims the clairaudient, as the ‘Man of Destiny’. KoS p.347

Regarding your question about the Khoina and their “secret weapon” of trained war-oxen, this should come as no surprise as the use is well documented in the historical records. Please see the rock-art sketch above or jump to Chapter 4.

Hello there Nicolaas

Yes, I do a lot of military-related writing, but my real interest and passion is comparative history. Many people revere Attila today, including the Mongolians, various Turkic peoples, the Bulgarians and the Hungarians, as these are linked to earlier or later formations of the Hun tribal confederation, which lasted a good long time. It appears Attila tried to revive it but died before he could secure the succession. It’s very interesting to see how his opponents demonised him, while his former subjects remember him with great respect. You could say he is to my people what King Arthur was to the Britons.

It’s fascinating to see Credo Mutwa’s comments on Attila, Caesar, Napoleon and others—he made a good point here. The idea that Napoleon and Attila covered essentially the same routes, using the same cities and rivers, holds some water, I think. Interestingly, both Attila and Genghis were told that the God of the Sky (their people recognise only one) had a destiny for them. Amazing!

What I find most striking is that the Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Magyars and Mongols were so similar to the Khoina—being all large-scale pastoralists with flocks and herds. I wonder if the Khoina language(s) have singular words for “herds of …”? In Hungarian, for instance, a herd of cattle on the hoof is “gulya”, the person in charge of them is the “gulyás”, so please don’t eat him! Same with the “herd of sheep” which is “nyáj” and so on.

I shall continue to follow your website as it contains some truly fascinating ideas that we simply weren’t taught at school!

Keep it up, and thanks again! Chris

Hi again Chris

Thanks for your enthusiastic reply. Attila’s origins and legacy is clearly a serious subject of study for you, understandably, and I appreciate your detailed remarks. The underlying ‘archaeology’ to Knot of Stone is itself a study of history’s great leaders and how they shaped modern Western society. To this end my book looks at historical events and their possible parallels in other parts of the world, most notably in South Africa. (I was born in Cape Town, where I spent most of my life). According to a clairaudient and practising psychitrist—and the one from whom I received the initial message regarding Almeida’s ritual killing—there are indeed links between Egypt’s eighteenth dynasty, thirteenth century China-Mongolia and twentieth century apartheid South Africa. That is, the political leadership of each epoch was, and still is, karmically connected. But more about that another time. It’s a separate chapter in my book.

Below is another clairaudiently received message, cited verbatim, as it appears in Knot of Stone. Please note that it is a rather rare and difficult piece which may not fit comfortably with your own views of the world. Since the Greek idea of the ‘eternal return’ (also called the ‘eternal recurrence’ by Nietzsche) is not readily acceptable in our society, I shall understand if you find its contents problematic. Well, so be it, such matters are not for everyone or, as Spinoza succinctly put it: “All things excellent are as difficult as they are rare”. Personally, I have no issue with this message, or several others in my book, as I believe each comes from a good source. I’ll leave you to judge for yourself:

I love your concept of the ‘eternal return’ and its development in the novel, as it appeals to my rather repressed oriental side which, occasionally, crawls out into the light of day. I also appreciate your gentle approach to reincarnation with its suggestion of never ending Life. I think your Synopsis is well thought out, too, and cleverly drafted. As a writer I know how difficult it is to condense one’s own text. I now understand why your publisher wanted to keep the references to Dan Brown and Umberto Eco; but I still believe Knot of Stone can, should, and will stand on its own without comparison.

Thank you, Arjuna, while my approach to the ‘eternal return’ could be unique, it is the clairaudient’s content about historical individuals and their recurrent lives that will, ultimately, stand on its own without comparison.