This old Volvo coupé is the one used by Sonja and Jason in Knot of Stone. It belongs to her brother Bart and was stowed by her parents in Lagos, Portugal, during his prolonged illness. (KoS p.137) Their trip is as much a journey through Europe’s diverse histories as it is one that unravels their own individual life stories.

This old Volvo coupé is the one used by Sonja and Jason in Knot of Stone. It belongs to her brother Bart and was stowed by her parents in Lagos, Portugal, during his prolonged illness. (KoS p.137) Their trip is as much a journey through Europe’s diverse histories as it is one that unravels their own individual life stories.

While the story behind Knot of Stone begins in June, the real journey starts in July when Sonja travels from Sagres to Paris. Joined by Jason in Lisbon, she finds herself driving across Europe hoping to unravel clues to the murder of Francisco d’Almeida five centuries before. Here we focus on the first castles, churches, museums and sacred sites visited in the book.

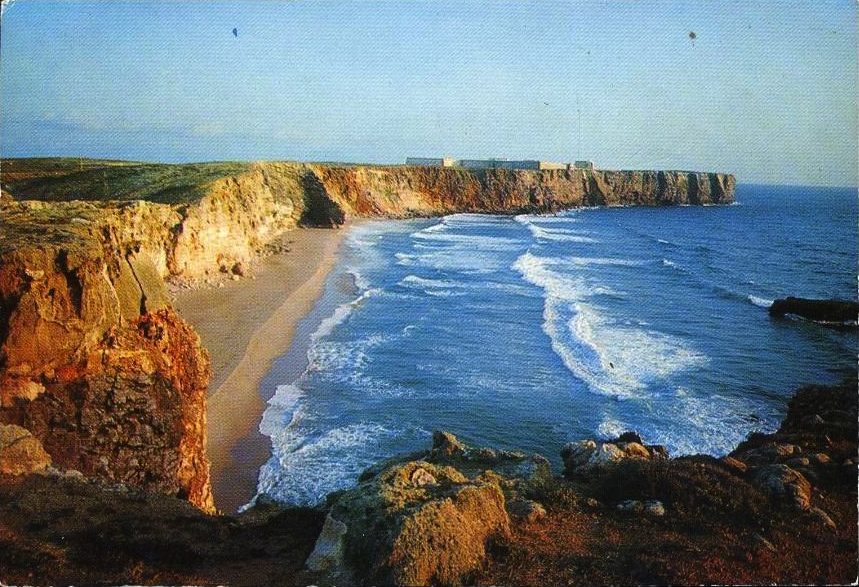

Fortaleza, Ponta de Sagres, Portugal (Chapters 25-27)

Sonja returns for a brief holiday in the Algarve, Portugal, where her parents have had a second home for decades. Visiting nearby Sagres she meets Volodya Vasilevsky (40), son of a Russian naval officer, and a man obsessed with Prince Henry’s school for navigators. Although the Sagres Academy wasn’t as sophisticated as scholars once claimed, it did serve as a school for neo-Templar initiates. Their studies, Volodya explains, were surrounded by secrecy as pre-Christian teachings—especially those taken from Greek and Arabic sources—had been long since suppressed. Moreover, those withholding arcane knowledge could be severely punished. (KoS pp.123-136)

Although the fortress dates from c.1650 and has been restored several times, it was from Sagres that Henry the Navigator initiated the Portuguese Age of Discoveries (Descobrimentos). Prince Henry was obsessed with the idea of an independent Christian king, a potential African ally who was neither Orthodox nor Catholic nor had any allegiance to Rome or Constantinople. Alas for him, the legendary Prester John was never found.

Although the fortress dates from c.1650 and has been restored several times, it was from Sagres that Henry the Navigator initiated the Portuguese Age of Discoveries (Descobrimentos). Prince Henry was obsessed with the idea of an independent Christian king, a potential African ally who was neither Orthodox nor Catholic nor had any allegiance to Rome or Constantinople. Alas for him, the legendary Prester John was never found.

Puerto de (port of) Sagres, Atlas de Pedro Texeira, 1634.

Puerto de (port of) Sagres, Atlas de Pedro Texeira, 1634.

While visiting the Algarve, Sonja walks across the Ponta de Sagres and stands, alone, watching the gulls swoop over the swirling sea. Here she finds the same solitude she’d felt at Cape Point (see below left), and is thrilled to know that she stands at the opposite end of that same ocean.

While visiting the Algarve, Sonja walks across the Ponta de Sagres and stands, alone, watching the gulls swoop over the swirling sea. Here she finds the same solitude she’d felt at Cape Point (see below left), and is thrilled to know that she stands at the opposite end of that same ocean.

Cape Point (left) and Ponta de Sagres (right) were once regarded as Holy Capes—one above the equator, the other below—and also linked to the pursuit for a priest-king somewhere in Africa (Abysinnia-Ethiopia). As part of a three-pronged approach, the Portuguese tried reaching East Africa via Cairo, the Congo River, and the Cape of Good Hope. But the far side of Africa was not to be found by transversing the continent—a fact White explorers would only discover for themselves centuries later.

Cape Point (left) and Ponta de Sagres (right) were once regarded as Holy Capes—one above the equator, the other below—and also linked to the pursuit for a priest-king somewhere in Africa (Abysinnia-Ethiopia). As part of a three-pronged approach, the Portuguese tried reaching East Africa via Cairo, the Congo River, and the Cape of Good Hope. But the far side of Africa was not to be found by transversing the continent—a fact White explorers would only discover for themselves centuries later.

Sonja’s map showing the places she will visit in Portugal.

Sonja’s map showing the places she will visit in Portugal.

Torre de Belém, Lisbon, Portugal (Chapter 28)

On her arrival, Sonja’s first choice is to wander down to the Tagus to see Belém Tower. The Torre de Belém was once the symbolic gateway to the new world and protected the entrance to Lisbon’s bustling port. It was only completed in 1515; that is, five years after Almeida’s empty ship came limping home. When news of his death at the Cape of Good Hope reached Lisbon, king Manual called for a day of national mourning. Named after Bethlehem, Belém itself was where the seafarers’ long journey South began. (KoS p.139)

Lisbon’s Torre de Belém overlooking the Tagus River as it flows toward the Atlantic.

Lisbon’s Torre de Belém overlooking the Tagus River as it flows toward the Atlantic.

Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, Lisbon, Portugal (Chapter 28)

That same evening, Sonja strolls over to the magnificent Jerónimos Monastery, founded in 1501, a mere four years before Almeida sailed for India, via the Cape of Good Hope. The cathedral was built beside the medieval city gates, over a chapel once used by Prince Henry, and served as a rite of passage for departing seafarers. It contains the tombs of both Gama and Camões and has, allegedly, the most beautifully proportioned claustro in all Christendom. (KoS p.139)

Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, Lisbon, viewed from across the water on Rua Bartolomeu Dias.

Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, Lisbon, viewed from across the water on Rua Bartolomeu Dias.

The great nave of the Jerónimos Monastery with its intricate Manueline carvings. Built in honour of king Manuel (who reigned 1495–1521), the entire building reflects his grandiose title as “the serene and all powerful ruler, on this side of the world and beyond the sea, and always visible”.

The great nave of the Jerónimos Monastery with its intricate Manueline carvings. Built in honour of king Manuel (who reigned 1495–1521), the entire building reflects his grandiose title as “the serene and all powerful ruler, on this side of the world and beyond the sea, and always visible”.

The beautiful cloister of the Jerónimos Monastery, restored in 2002, with its eclectic stone ornamentation.

The beautiful cloister of the Jerónimos Monastery, restored in 2002, with its eclectic stone ornamentation.

Museu de Marinha, Lisbon, Portugal (Chapter 30)

Sonja and Jason visit the Maritime Museum, also in Belém, and find it stuck in a by-gone era. Here Portugal’s Age of Triumph appears defiant in a world of relative sensibilities and negotiated histories. Nevertheless, the museum has a bright portrait of Almeida—shown in a long billowing coat—not unlike the one they discovered in the British Library. (KoS pp.65, 150-151)

Façade and entrance (bottom right) of the Museu de Marinha, Lisbon, structurally part of the old monastery.

Façade and entrance (bottom right) of the Museu de Marinha, Lisbon, structurally part of the old monastery.

Francisco d’Almeida’s portrait in the Maritime Museum.

Francisco d’Almeida’s portrait in the Maritime Museum.

Centro Cultural de Belém, Lisbon, Portugal (Chapter 30)

Located between the magnificent Jerónimos Monastery and Belém Tower, the Cultural Centre of Belém (CCB) is a most striking monument to modern design and architecture. Completed in 1992 to host Portugal’s presidency of the European Union, the building was as controversial as the idea of a single EU community itself. The democratic ideal of a unified Europe is a leitmotif in Knot of Stone. In our story, Sonja and Jason visit the CCB at the end of their first day in Lisbon. (KoS pp.148, 150)

The CCB’s riverfront garden and shaded patio is a cool place to relax at sunset, especially in summer, as Sonja knew from previous visits to Lisbon. The castellated structure resembles a medieval town with intersecting “streets” and “squares”, echoing its function as a conference, performance and exhibition venue. (KoS p.148)

The CCB’s riverfront garden and shaded patio is a cool place to relax at sunset, especially in summer, as Sonja knew from previous visits to Lisbon. The castellated structure resembles a medieval town with intersecting “streets” and “squares”, echoing its function as a conference, performance and exhibition venue. (KoS p.148)

Linking the building’s interior and exterior, this transversal “street” also connects the Jerónimos Monastery with the riverside Tower of Belém. The red carpet symbolically recalls the annual procession of departing sailors who, following their king and bishop, walked from the church to their ships. As many had done before, Almeida and his men followed the same “rite of passage” down to the Tagus. (KoS p.139)

Linking the building’s interior and exterior, this transversal “street” also connects the Jerónimos Monastery with the riverside Tower of Belém. The red carpet symbolically recalls the annual procession of departing sailors who, following their king and bishop, walked from the church to their ships. As many had done before, Almeida and his men followed the same “rite of passage” down to the Tagus. (KoS p.139)

Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, Portugal (Chapter 31)

On visiting the National Archives, Sonja discovers that Almeida’s brother Pedro argued with king Manuel and subsequently promised to leave Portugal should Almeida be escorted safely back from India. What was their argument about and, moreover, why should Pedro offer to leave the country? Had the family been disgraced? Was Almeida dishonoured? Follow Sonja as she unravels the clues to his murder. (KoS pp.152-158)

The Torre do Tombo (now called the Institute of the National Archives) houses many of Portugal’s oldest records, some dating back to 1378, including those dealing with the Age of Discoveries (Descobrimentos). Although the Church only began recording births, marriages and deaths from 1550—a generation or so after Almeida himself lived—the archive provides an invaluable source of information for Sonja and Jason.

The Torre do Tombo (now called the Institute of the National Archives) houses many of Portugal’s oldest records, some dating back to 1378, including those dealing with the Age of Discoveries (Descobrimentos). Although the Church only began recording births, marriages and deaths from 1550—a generation or so after Almeida himself lived—the archive provides an invaluable source of information for Sonja and Jason.

Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo, Abrantes, Portugal (Chapter 32)

Using their Volvo, Sonja and Jason drive into the country to visit the Almeida family seat, Castelo de Abrantes, in the heartland of Portugal. Here they discuss Almeida’s career and attachment to his wife and daughter. The castle towers above a bend in the Tagus River and, once captured from the Moors in 1148, became a strategic Templar stronghold and dominion of the Order of Santiago de Compostela—to which Almeida’s forefathers also belonged. Within the ramparts of the castle, now much in ruins, stands the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The church also served as a private chapel and family tomb, and is the only surviving building from Almeida’s lifetime. It is used as a family museum today. (KoS pp.159-160)

Inside the Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo are the tombs of Almeida’s father, mother and brother. The church has green azulejos tiles behind the altar and a flagstone floor worn smooth by the tears of countless generations. Beside a few sculptures and a carved baptismal, little else survives what Almeida himself may have seen—except for two tipo gótico frescoes, of which one depicts a Templar knight slaying a dragon.

Inside the Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo are the tombs of Almeida’s father, mother and brother. The church has green azulejos tiles behind the altar and a flagstone floor worn smooth by the tears of countless generations. Beside a few sculptures and a carved baptismal, little else survives what Almeida himself may have seen—except for two tipo gótico frescoes, of which one depicts a Templar knight slaying a dragon.

São Jorge, Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo, Abrantes.

São Jorge, Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo, Abrantes.

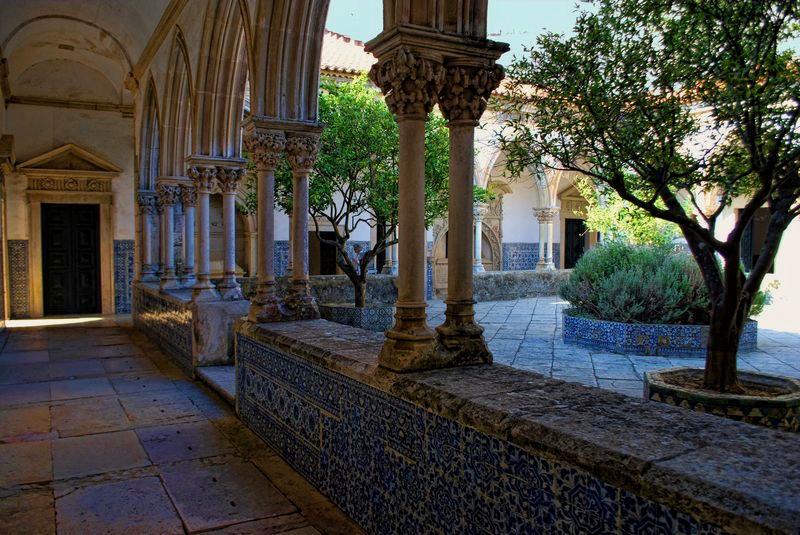

Convento de Christo, Tomar, Portugal (Chapter 33)

The twelfth-century Convento de Cristo served to defend the Christian border against the Moors. At the centre of this magnificent monastic fortress stands the Charola, or Round Church, built by the Knights Templar and modelled on the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Its octagonal design demonstrated the Templarist view that Jerusalem, rather than Rome, was the historical link between East and West. (KoS p.165)

As a former Templar stronghold, the Convento was well suited for the headquarters of the Order of Christ. Knights who belonged to this Order were neo-Templars. (KoS pp.129-131)

The Gothic-style Claustro do Cemitério was used as a cloistered cemetery for knights and monks in the Order of Christ. Here Almeida’s forefather, Vasco Gonçalves de Almeyda and his wife, then governors of the young Prince Henry, donated a side chapel for his private use. (KoS p.165) Pictures courtesy of Fernando Fidalgo.

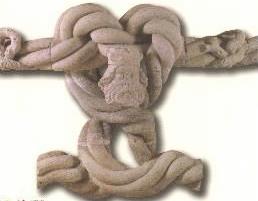

The Convento’s gradiose 16thC ediface is adorned with emblematic Templar symbols and—like the rock-hewn churches of Ethiopia—appears entirely cut from one single stone. Here Sonja and Jason find further examples of twisted Manueline knots made of coiled rope.

The Convento’s gradiose 16thC ediface is adorned with emblematic Templar symbols and—like the rock-hewn churches of Ethiopia—appears entirely cut from one single stone. Here Sonja and Jason find further examples of twisted Manueline knots made of coiled rope.

To read about the symbolism of the knot and why we chose this for the title of our book, see How to tie a Knot in Stone.

Nicolaas Vergunst

Hello Nicolaas, um prazer conhecer-lhe.

I am very happy to have found your blog. I am Portuguese, living in the UK, and passionate about Portugal too. It is always nice to discover a passion in people, especially through the places they like.

Although I was born in Lisbon and spent most of my childhood in Sintra, I never really got to know our capital as I was more familiar with the Cascais and Estoril coast near Sintra and, too, the north of Portugal where my grandfather still lives. About four years ago, while at university, we visited Lisbon as part of an Urban Regeneration project, and it was my first proper chance to get to know the city. We visited many places, most of which I’d never seen before. The old, the new, and the completely modern. We learnt about the history of the city, as well as the current reality, through all its urban and social changes. It was a very rewarding and enlightening experience. Since then I have been back many times, as I have a strong connection to the city. I also love other parts of Portugal, and always like to discover new places. It is a beautiful country, always in my heart.

Lovely to have found you. As melhoras para voce. Sergio

What Nicolaas doesn’t mention in his book is how damn hot and humid it gets in Lisbon, or how sore and tired my feet were after traipsing from place to place in Portugal. Instead, he ends this leg of our trip with some ogrish man following us. That’s all very nice for his plot, but it offers no rest for us characters!