Modern technology has transformed our societies, bringing remote and distant corners of the world together. Watch this animation to see how industrialisation, transport networks, electricity and telecommunications have united people around the globe. This video was produced for the 2012 Planet Under Pressure conference in London. You can also watch the narrated version here.

In a world without end, spinning endlessly in space, is there such a thing as an East or West and, if so, where does the one end and the other begin?

Cradle of Civilisation

Cradle of Civilisation

Is the East-West division between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, the legendary home of the Garden of Eden and our so-called Cradle of Civilisation? Mesopotamia itself means “between rivers” and fits, some scholars claim, the biblical description of Paradise. Others believe the human species originated in Africa and dispersed via the Rift Valley corridor onto the Eurasian plains. However, the Fertile Crescent still remains the most accepted home for the birth of our first cities; that early building block of civilisation. If so, is it from Mesopotamia (today Iraq) that civilisation spread eastwards and westwards, towards the periphery?

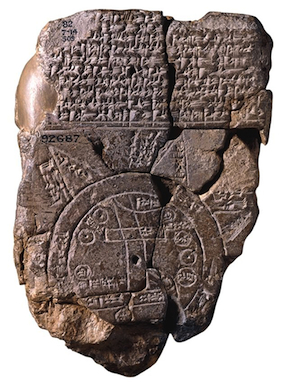

Above right: oldest known world map, 6thC BCE, Babylonian clay tablet. Courtesy British Museum, London.

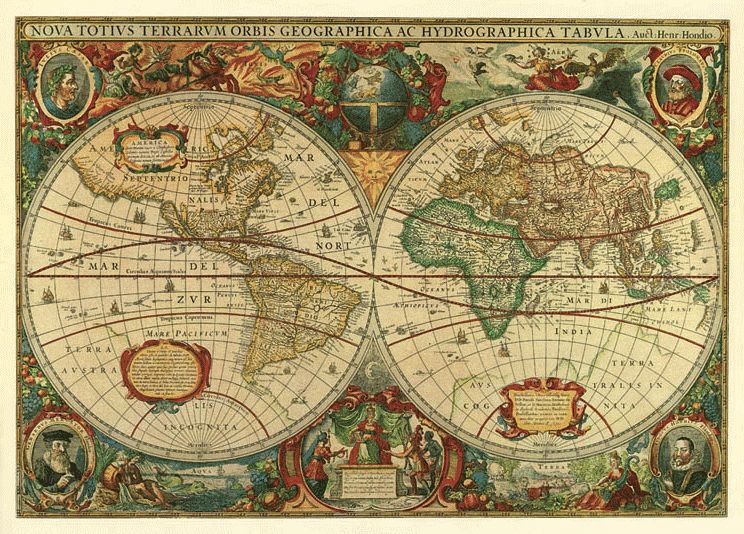

‘Nova totius Terrarum Orbis’ by Hendrik Hondius, Amsterdam 1630. A typical 17thC world map showing two halves of the globe. The East shows both Eurasia and Africa (including the newly sighted Australian coast) and the West the two recently colonised Americas.

‘Nova totius Terrarum Orbis’ by Hendrik Hondius, Amsterdam 1630. A typical 17thC world map showing two halves of the globe. The East shows both Eurasia and Africa (including the newly sighted Australian coast) and the West the two recently colonised Americas.

Unlike the narrow Rift Valley gorge, Eurasia’s open plains and vast plateaus provided a favourable passage for migrating clans and their herds. So, was it on the Russian steppe or in the Iranian deserts that sweeping hordes and conquering armies first crossed from East to West? And if so, which horizon separated the lands of the rising sun from those over which the moon set?

Great Cities

Or, instead, did East and West meet along the Bosphorus where various cultures bumped into each other over several millennia? Here Byzantium-Constantinople-Istanbul saw all manner of Greeks, Romans, Latins and Turks step across the great divide. Or was it in Jerusalem, perhaps, where Jews and Christians and Muslims have rubbed shoulders for countless centuries? Jerusalem was, after all, the conceptual centre of the world. Or, was it perhaps in Berlin where, until only a few decades ago, capitalists and soviets faced each other across the Wall? During the Cold War, c.1946–1991, the wall symbolically divided East from West, separating what had once grown and belonged together.

But is it a river, a mountain, or a wall after all? Or is it, say, a crossroad, trade route or military frontier? Or a set of borders, like the state lines dividing Eastern America from the American West? Like most borders these lines arbitrarily divide natural, traditional and even seasonal territories.

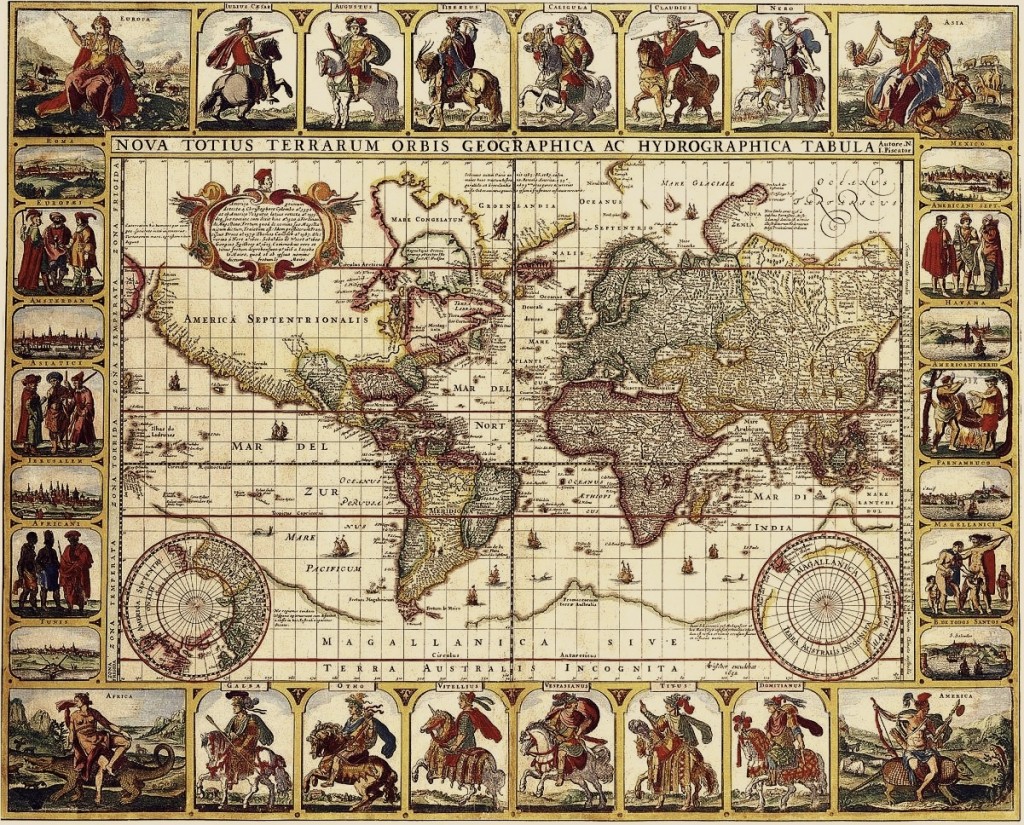

Another ‘Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis’ world map by a 17thC Dutch cartographer, Claes Janszoon Visscher, showing the Tordesillas meridian that divided the non-Christian world into two halves: one part going to Portugal the other to Spain. This map was published in 1652, the year in which the Dutch took possession of the Cape of Good Hope.

Another ‘Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis’ world map by a 17thC Dutch cartographer, Claes Janszoon Visscher, showing the Tordesillas meridian that divided the non-Christian world into two halves: one part going to Portugal the other to Spain. This map was published in 1652, the year in which the Dutch took possession of the Cape of Good Hope.

Open Oceans

Or could it be out to sea, perhaps, somewhere in the Atlantic? Historically, the Pope divided the earth in two, pole to pole, along an imaginary line in the mid-Atlantic, giving Spain one half of the world and Portugal the rest. Excluding Europe, of course. On that day, 7 June 1494, the Western territories included a still unknown America and the Eastern hemisphere all of Africa—though its full extent still had to be discovered. Known as the Tordesillas meridian, the line of demarcation brushed the right shoulder of Brazil which, officially, would only be discovered in 1500.

That was then, but what about today? Perhaps it is the Greenwich prime meridian that determines where we are in the world today? It marks zero longitude and we use it to orientate ourselves spatially and to relativise our time on an East-West basis. Significantly, this places Europe in the East and pushes Africa towards the Orient—an orientation that suits China today!

For now, the question is not where but when did East and West meet? It’s a question that always vexes me because, as a westerner, I can’t step outside my own shoes. Questions of relativity require both feet on the ground and, simultaneously, a head above the rest. Nevertheless, the question does force us to rethink our histories.

The first separate map depicting the African continent, alone, from Sebastian Munster’s ‘Cosmography’, Basel 1545. It is full of fanciful details based on the work of Ptolemy and Herodotus, including a one-eyed giant called Monoculi, mythical guardian of the Cape of Storms. Despite the fact that the southern tip had been rounded a half century before, landmarks along the coast still remain unnamed.

The first separate map depicting the African continent, alone, from Sebastian Munster’s ‘Cosmography’, Basel 1545. It is full of fanciful details based on the work of Ptolemy and Herodotus, including a one-eyed giant called Monoculi, mythical guardian of the Cape of Storms. Despite the fact that the southern tip had been rounded a half century before, landmarks along the coast still remain unnamed.

Cape of Good Hope

The East-West line has clearly shifted over time and, from a Western perspective, reflects the ebb and flow of Europe’s overseas expansion. For instance, during the Age of Exploration c.1400–1600, the southern tip of Africa became the new threshold between an ancient East and a modern West. The Cape of Good Hope was then the southernmost Portal to the Indies and one of the most dangerous known to man. Ironically, it’s known as the Fairest Cape today.

Towering above Cape Town, Table Mountain was once seen to personify the character of a Stormy Cape. The mountain was a wild and vindictive giant called Adamastor, a tormented figure derived from Greek mythology. Like the Titans, Adamastor dashed all hopes of passing mortals. The Cape was his forbidden portal, a threshold between the Atlantic and Indian oceans, beyond which neither ship nor sail should pass.

Artist’s impression of the giant Adamastor, showing the Portuguese fleet rounding the Cape of Good Hope. Courtesy Marina dos Santos Salgueirio Tomas Teixeira.

Artist’s impression of the giant Adamastor, showing the Portuguese fleet rounding the Cape of Good Hope. Courtesy Marina dos Santos Salgueirio Tomas Teixeira.

The long voyage East, amid raging storms and inner temptations, symbolized a journey of spiritual enlightenment. It was a concept that possessed Prince Henry and the explorers of Atlantic-Africa, a concept that also transformed the oceanic ‘Discoveries’ into a quest for individual spiritual enlightenment. Portugal’s exploration from West Africa to East Africa, from the shores of the Atlantic to the Indian seaboard, was thus more than a mere adventure in maritime geography. And thus, in 1488 a weatherworn Bartolomeu Dias first crossed this great divide, unknowingly, after being driven out to sea in a storm. For more images of Table Mountain, see Hoerikwaggo: Images of Table Mountain.

A decade later, on his historic outbound voyage to India in 1497, Vasco da Gama too clashed with Adamastor off the Cape. Their confrontation came to symbolise the conflict between modern man and the classical gods. For Luís de Camões, poet laureate of Portugal, the clash symbolised mankind’s inevitable triumph over the gods, a triumph of the Renaissance over the Medieval, of humanism over dogmatism.

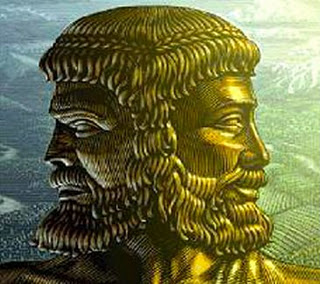

Table Mountain has also been likened to the double-headed god Janus (Ianus) of Roman mythology. Looking forward and back, he was the awe inspiring Door- or Gate Keeper. Janus looks ahead and behind, knowing the future as well as the past. Likewise, Table Mountain watched over the African continent, protecting it from men sailing from the Atlantic into the Indian Ocean, West to East, from new to old, cold to warm. Or so it was until 1869, when the Suez Canal opened.

Before the Canal, the Cape of Good Hope had offered the most direct sea passage to the Indies. Like the once impassable Pillars of Hercules, Table Mountain helped to create a concept of an intermediary Africa. With northern and southern portals at Gibraltar and the Cape, respectively, Africa mediated between a fabulous East and a robust West. To this end the Portuguese also tried to reach the other side of Africa via the Congo River, but malaria thwarted their efforts (as it did during the building of the Panama Canal in the 1880s and 1900s). Be that as it may, the East was not to be found by transversing the continent. A fact White explorers would only discover for themselves centuries later.

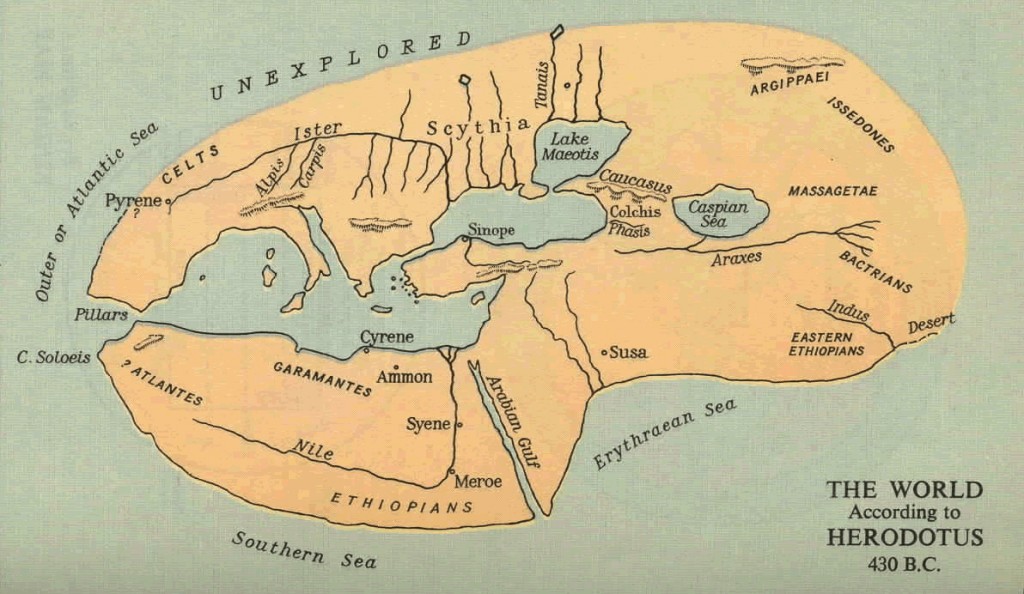

A model of the known world according to the Greek geographer and ethnographer Herodotus, the so-called Father of History. His view of the inhabited world, spread out on an East-West axis, was to have a lasting influence on western historians.

A model of the known world according to the Greek geographer and ethnographer Herodotus, the so-called Father of History. His view of the inhabited world, spread out on an East-West axis, was to have a lasting influence on western historians.

Some alternatives

Traversing a continent along its East-West axis is not new, of course. Early long-distance migrations followed the same pattern, moving within compatible climatic zones. Moving laterally allowed caravans and armies to harness the same pack animals, gather the same food and, so far as was possible, to avoid new diseases. To the North lay ice and bitter cold. South the sand and scorching heat. For contemporary geographers the world was elliptical, or elongated, with an East-West to North-South ratio of 5:3 (see map above).

The main East-West route ran from the Chinese capital of Chang’an (Xian today) via the Himalayan valleys and Afghan passes, and then across the Arabian Desert to the port-cities of the eastern Mediterranean. Exchange along this line of oases, once known as the Khurasan or “Old Silk Road”, prepared the ground for varied beliefs; blending cultures and promoting religious tolerance. All the great conquerors of Eurasia—Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan and Tamerlane—used this route while criss-crossing the continent.

Modern copy of the ‘Tabula Rogeriana’ by Muhammad al-Idrisi, the Muslim geographer and traveller from Ceuta (opposite Gibraltar), for King Roger II of Sicily, 1154.

Modern copy of the ‘Tabula Rogeriana’ by Muhammad al-Idrisi, the Muslim geographer and traveller from Ceuta (opposite Gibraltar), for King Roger II of Sicily, 1154.

The expanding Muslim empire had an East-West axis too, as well as a formidable array of Ottoman, Mamluk and Zamorin fleets that controlled the main trade routes from the Strait of Malacca to the Strait of Gibraltar. Their oceanic network had evolved as an alternative to the heavily taxed and bandit-ridden routes across the Eurasian continent and, of course, following disruptions caused by the great marauding warlords.

By 1500 the centre of this vast commercial network was the Middle East and not the Mediterranean. Venice was an exception, being a mercantile linchpin for Jews, Turks and Christians. The rest of Europe was of limited value, and Portugal merely peripheral. The West had no raw materials or manufactured goods to offer India, China or Japan—except imported gold and silver. And thus without Africa’s gold there would have been no grand sea-trade in the sixteenth century and, subsequently, no modern world economy.

Perched on Europe’s most south-westerly corner, Portugal was ideally positioned for its westward expansion. Pre-empting the discoveries of the 15thC, old Phoenicia had faced west too. Likewise the powers that would succeed Portugal—Holland and England—also faced the Atlantic. But it was not the open sea alone that gave them an advantage, it was the prevailing Westerlies that blew at their backs. As a result, the world opened up westward. In short, it was the East that first discovered the West and not the other way around. But this history is best told another day.

NASA satellite reconstruction of the oceans in motion. Courtesy of National Geographic, February 2013. White lines show the flow of currents in the Atlantic and Indian oceans while the swirling eddies indicate where these are disturbed by land and wind.

NASA satellite reconstruction of the oceans in motion. Courtesy of National Geographic, February 2013. White lines show the flow of currents in the Atlantic and Indian oceans while the swirling eddies indicate where these are disturbed by land and wind.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Perhaps when or where the two meet is not as important as why we need both to make us feel whole? For now I’m sure of only one thing, we orientate ourselves by facing three directions: the rising sun, the open sea and the way forward. This is the result of ceremonial, conceptual and navigational necessity. Seen from outer space, of course, our planet has neither a top nor a bottom, nor an East or a West. Thankfully.

Heart-shaped (cordiform) map projection by the French mathematician and cartographer Oronce Finé, 1534.

This article was first published in the United States by World Report: The Student Journal for International Affairs (Autumn 2011).

Nicolaas Vergunst

Your East meets West blog story gives a great overview for anyone interested in history and international relations. As a group of young film makers in Europe we have also explored this theme in a short video called the Mystery of Love. We like the animated Globaïa video and Finé’s world map in the form of a heart! Esmoreit and Flore Lutters

Great read… I especially liked your depiction of Table Mountain as Adamastor! Intriguing indeed how our history has progressed…

Very interesting to read. Thanks : )

I’m delighted to see you back on our page, Chitra, and to hear from you again. Glad you enjoyed our East-West story.

In Nederland had je de VOC (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie) en de WIC (West-Indische Compagnie).

While your comments are of interest and appreciated, Edwin, they do not add to the specific content of this page. May I suggest you first read Knot of Stone or, at least, look at our homepage to inform yourself of the novel’s historical scope and cultural perspective.

My apologies. I wanted to suggest the following. The Dutch divided their world into two parts. The East and the West. Het handelsgebied van de Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie strekte zich uit van Kaap de Goede Hoop tot Japan. Het handelsgebied van de WIC was gelegen tussen twee meridianen: als westgrens de meridiaan door de oostpunt van Nieuw-Guinea en als oostgrens de meridiaan van Kaap de Goede Hoop.

Curiously, the Cape of Good Hope also served as a boundary for Portugal’s Estado da Índia after the overseas empire had been established by Viceroy D’Almeida, the central character in Knot of Stone. It was at the Cape itself, on the western border of Almeida’s realm, that the witches predicted his ill-fated death. See my reference to the witches of Cochin and their prophecy.

Er is een vreemde versie van de Germaanse mythologie. In Nederland zijn er plaatsen die verwijzen naar deze mythologie, zoals Hellegatsplein, Hellegat, etc. Vanuit het Westland zouden de doden reizen naar Engeland.

Thank you, Edwin. From a proto-Dutch or Frisian perspective—as too for the Saxons, Franks and Galicians facing the ocean—the open sea was where the sun went each day and where the departed souls journeyed in the afterlife. Thus to the West, across the Atlantic, lay their future. Similarly, the modern Atlantic nations—Holland, England, France and Portugal—became great naval powers whose future lay across the Atlantic. Curiously, the Phoenicians had faced west too and pre-empted the Age of Discoveries. (KoS p.135)

This is amazing.

West meets East in ‘Portugal, Jesuits, and Japan’ exhibition at Boston College’s McMullen Museum of Art. Click here for more images.

That the Treaty of Tordesillas was signed in June 1494, a mere six years after Dias’s landing at the Cape, shows how fast history was moving.

Interesting, is it still in use today, the Treaty of Tordesillas?

The meridian doesn’t exist today, Deenanath, although Chile and Argentina recently used the Treaty of Tordesillas to claim their part of the Antarctic and Falklands, respectively. Until 1898 the treaty divided territories between Spain and Portugal, and thus shaped modern Latin America. However, already long before this other nations simply ignored the treaty and extended their colonial powers on both sides of the line: “If you can take it, even if it belongs to others, then its yours.” This rule governed the expanding new world. Read further here: Treaty of Tordesillas.