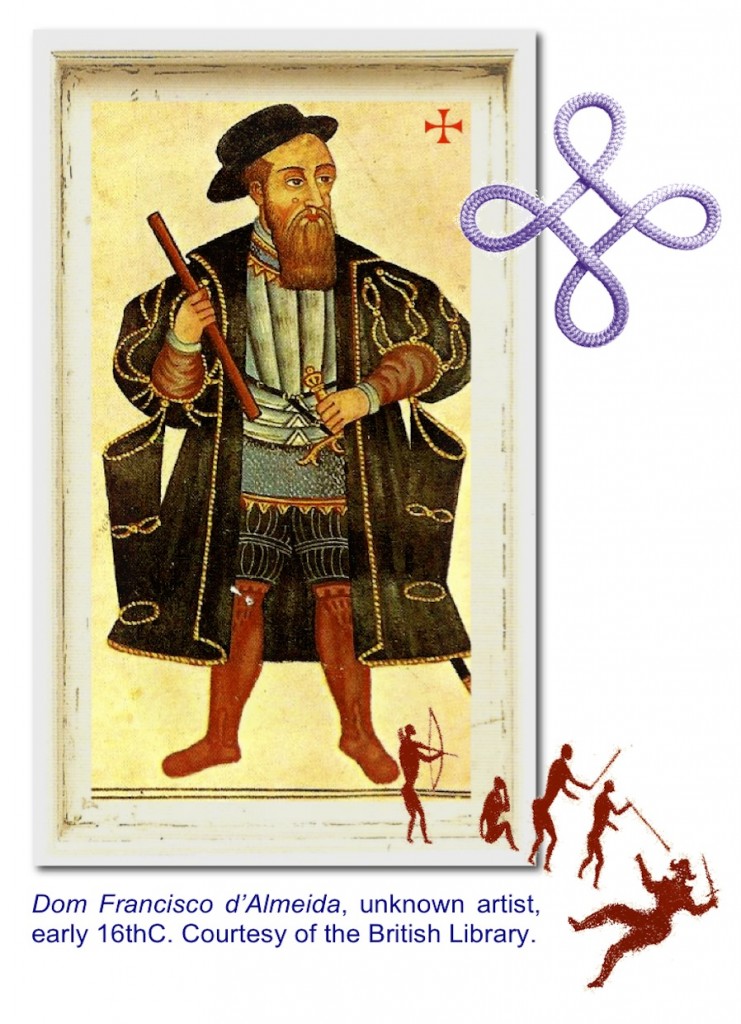

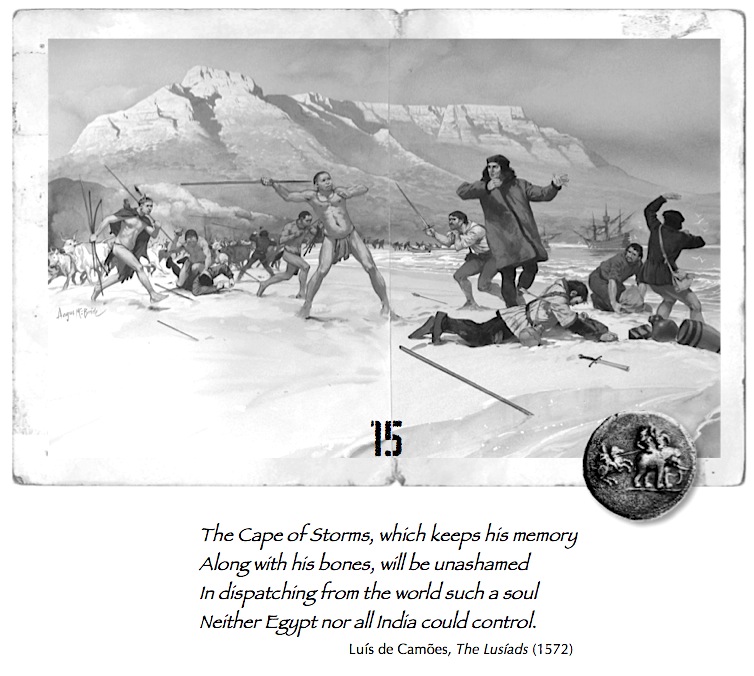

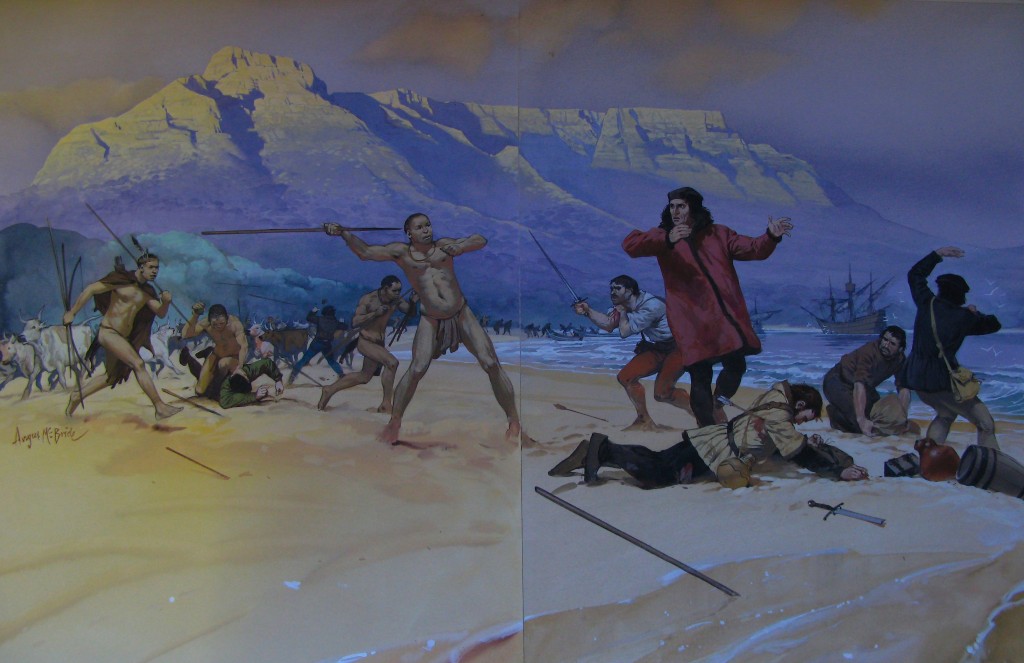

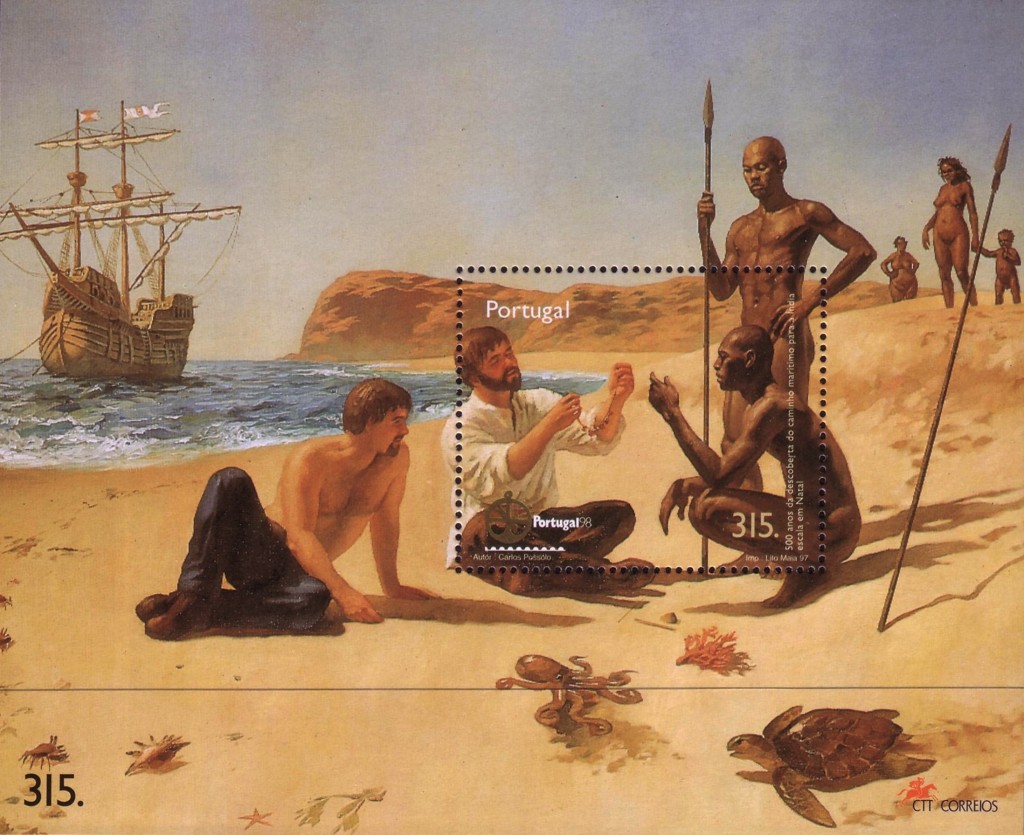

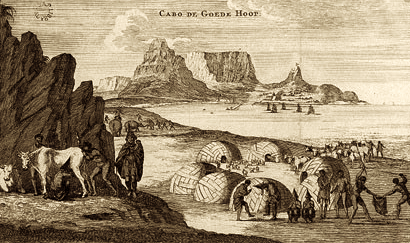

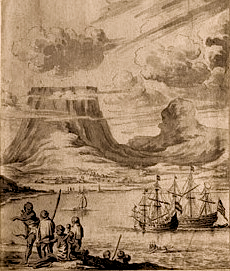

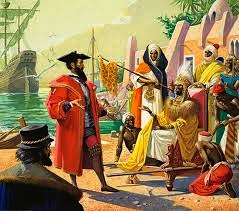

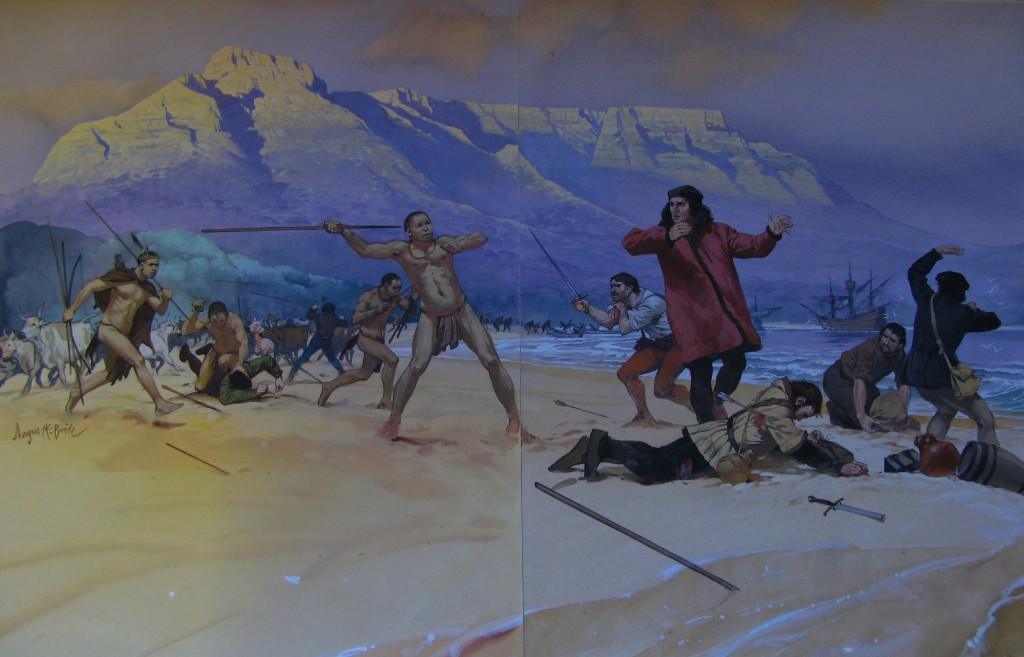

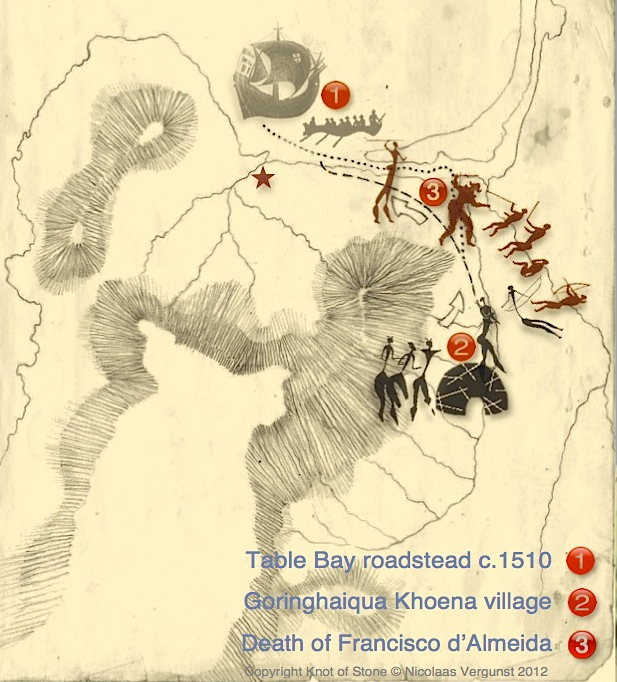

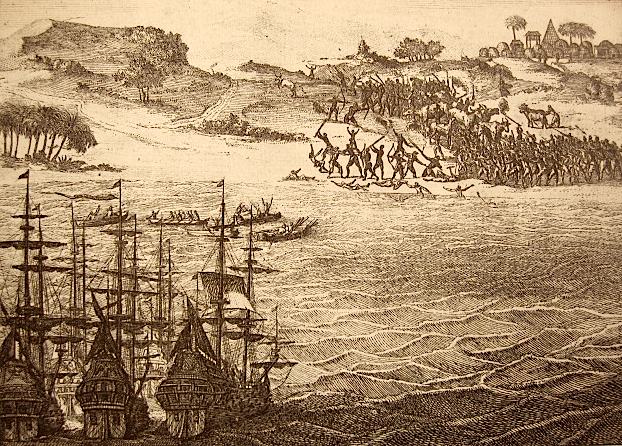

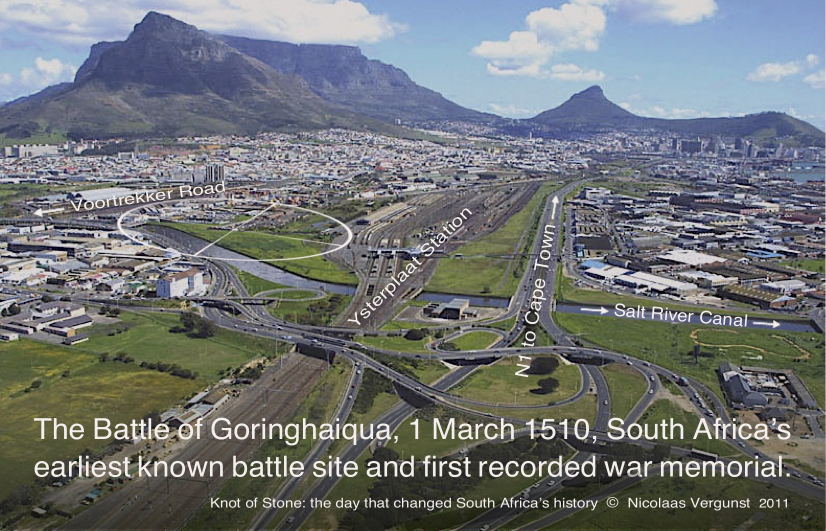

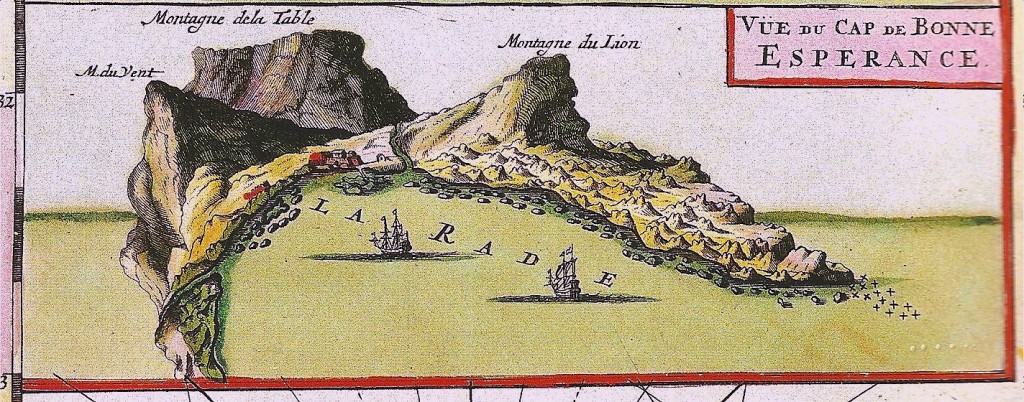

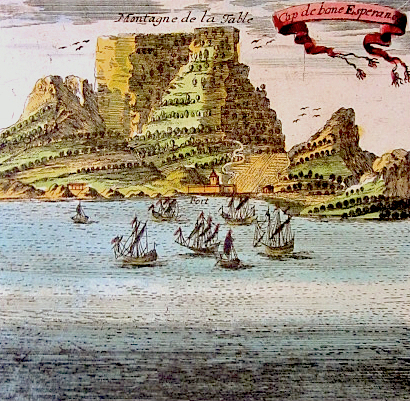

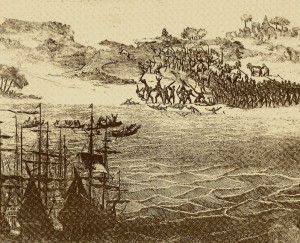

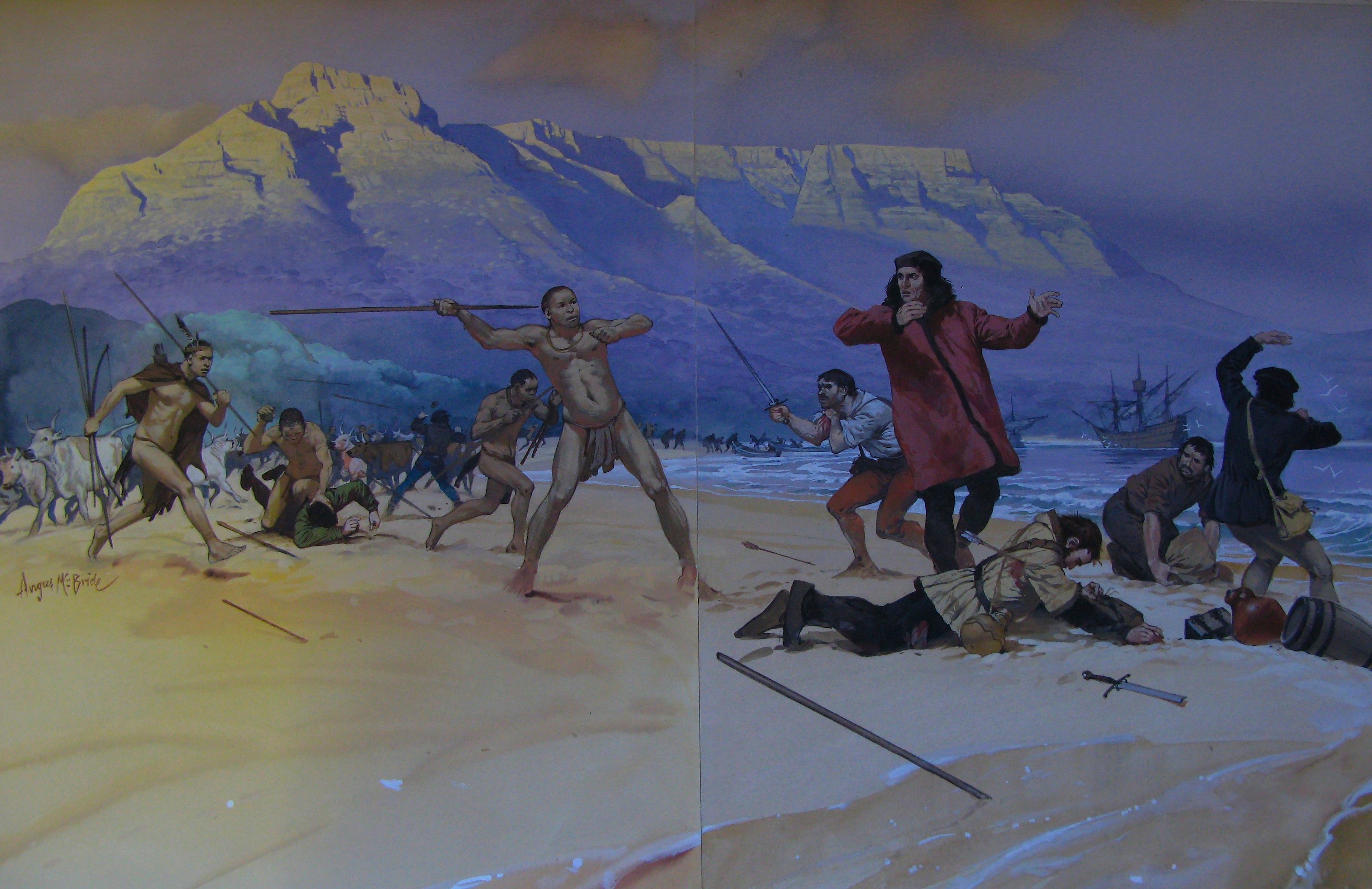

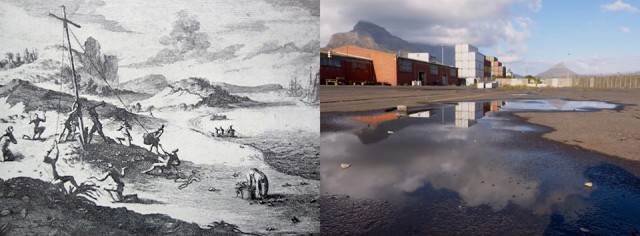

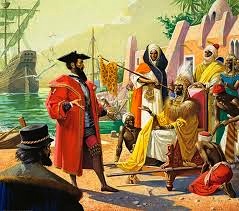

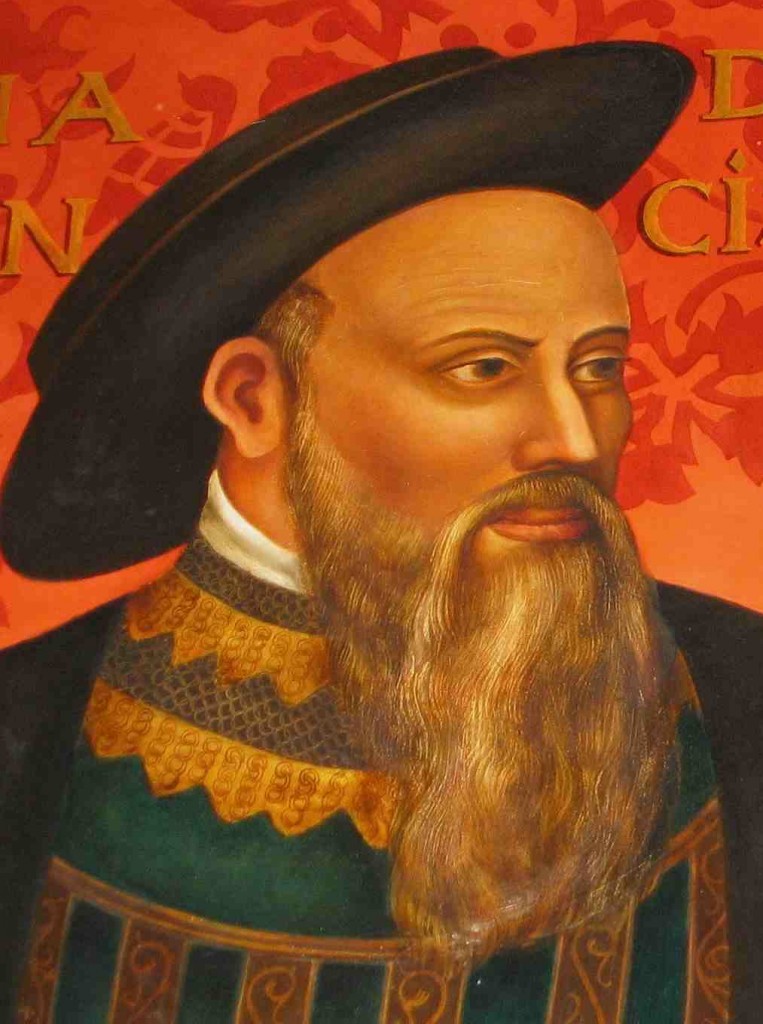

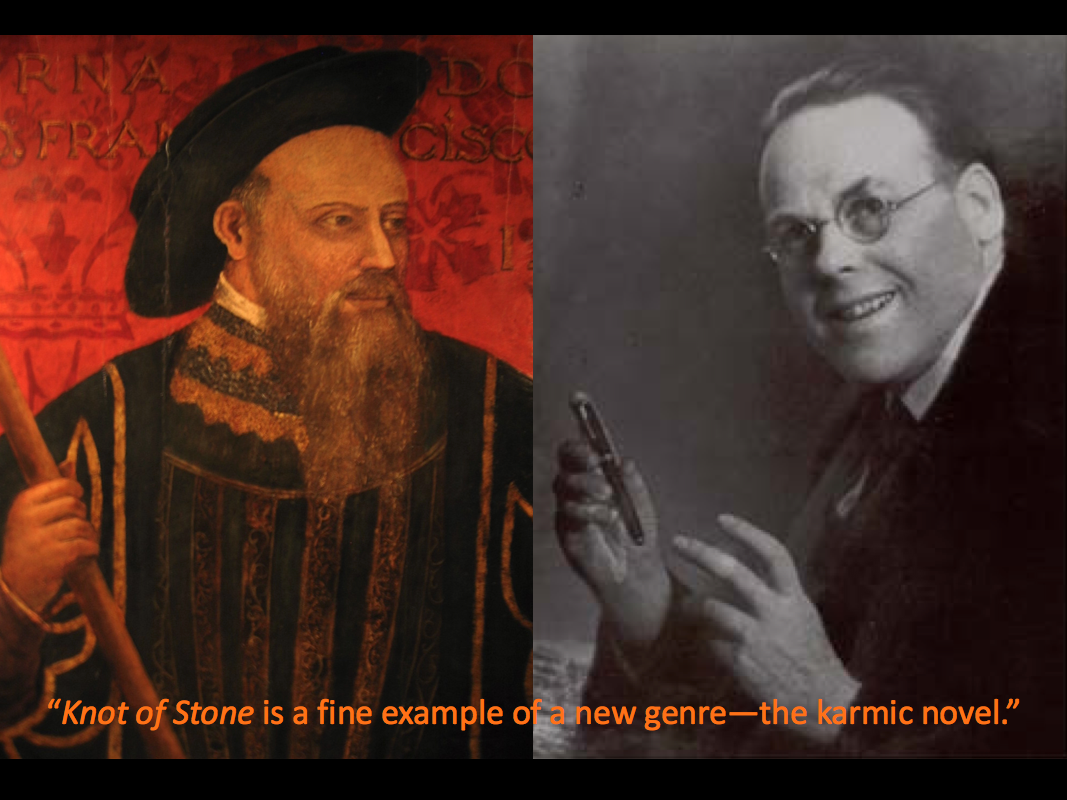

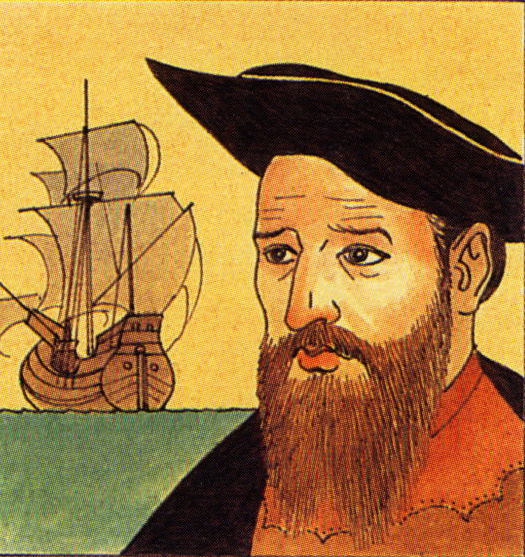

In 1510 Francisco d’Almeida, former Viceroy of Portuguese territories in India, was on his way home when he and his men went ashore to take in water and food at present-day Cape Town. According to historical sources, he was killed in a skirmish with the Khoekhoen (Hottentots) and buried on the beach. His grave has never been found. The skirmish took place at Aguada de Saldanha, the name then used by the Portuguese for Table Bay.

In 1510 Francisco d’Almeida, former Viceroy of Portuguese territories in India, was on his way home when he and his men went ashore to take in water and food at present-day Cape Town. According to historical sources, he was killed in a skirmish with the Khoekhoen (Hottentots) and buried on the beach. His grave has never been found. The skirmish took place at Aguada de Saldanha, the name then used by the Portuguese for Table Bay.

While such an ignominious death seems unlikely for a high-ranking officer in the company of veteran soldiers, it passed into official history and has never been questioned. After this incident, fearing more attacks, the Portuguese did not care to take possession of Africa’s southernmost coast. It was only in the mid-17th century that Dutch settlers established themselves at the Cape.

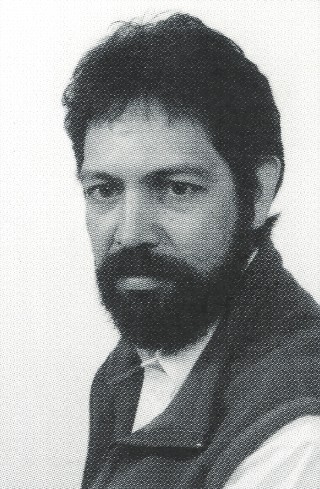

Some four centuries on, in 1924, the German Waldorf School teacher Walter Johannes Stein (1891–1957) had an inner vision in which he saw this event and recognised the victim as his own earlier incarnation. In the same year Rudolf Steiner confirmed this insight—formally identifying Stein with Almeida. In his “retrospective vision” Stein saw how Almeida, a knight and confidante of kings, had been ritually killed by his own men. He understood that this death was an execution carried out at the request of the Spanish-orientated Order of St James (Ordem de Sant’Iago), for whom Almeida had once served as a commander-in-arms.

Stein remembered too that, as Almeida, he had been wounded in the siege of Moorish Granada when it fell to the Spanish in 1492. During this campaign he recuperated in the house of a Muslim nobleman who, subsequently, gave him an unknown Aristotelian treatise about the secret properties of nature. After being nurtured back to health, Almeida left Granada with this precious book and a mysterious pearl, also a gift. The latter was apparently an alchemical reliquary. Though bound by oath to submit such things to the Order, he made them available to the German alchemist Basilius Valentinus. For this act of ‘betrayal’, the Order issued an unofficial request for Almeida’s execution.

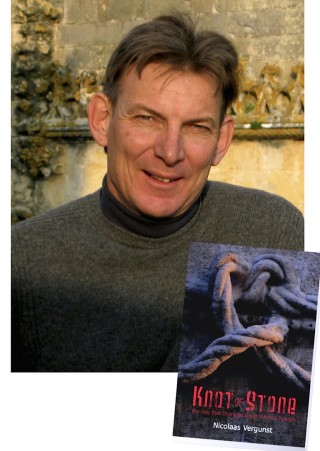

Various publications by and about Stein drew the attention of other researchers of spiritual history to Almeida. Through anthroposophical channels Stein’s investigations into the circumstances around Almeida’s death also reached Cape Town. Rachael Clayfield, a priest of the Christian Community, investigated Stein’s claims and shared the fruits of her research in the early 1980s. Among those Rev. Clayfield spoke to was Nicolaas Vergunst, a young man of Dutch descent and born in Cape Town.

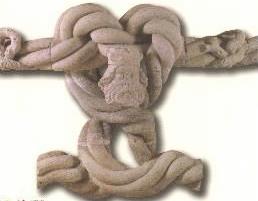

After a career with the national museums of South Africa, Nicolaas Vergunst started his own research into Almeida’s murder. This has resulted in a fine and well-documented novel, entitled Knot of Stone: the day that changed South Africa’s history, published in September 2011. The book commemorates the death of Almeida and attempts to unravel the mysteries around this death and its long-term implications. The genre of this kind of mystery literature has been made famous by books of Umberto Eco, Dan Brown, Paulo Coelho and others. Readers will find in Knot of Stone an eloquently written and fascinating book that surpasses others in this genre; offering a lot of well-grounded spiritual facts instead of esoteric fantasies.

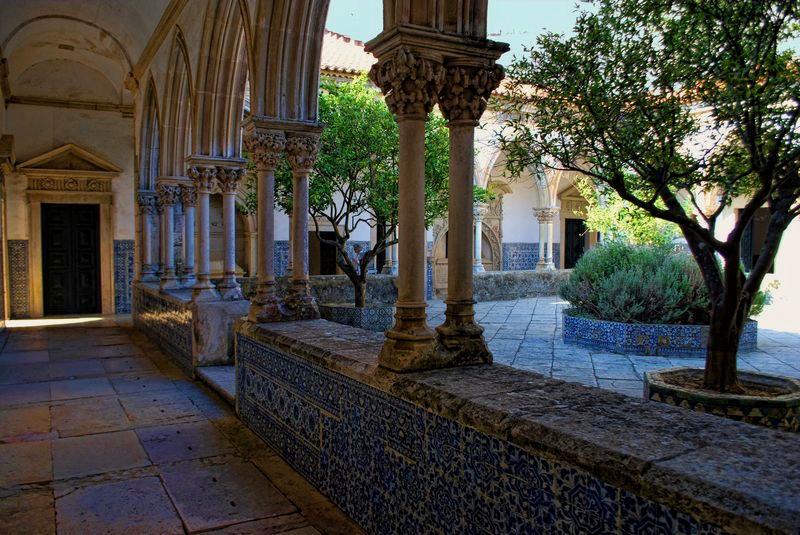

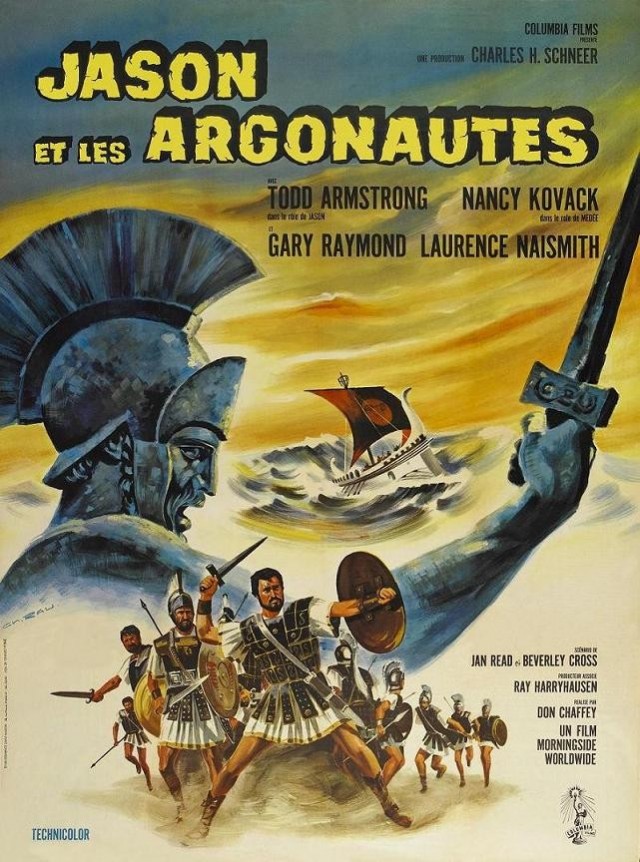

The story is presented as a journey initiated by the chance discovery of Almeida’s bones. A South African archaeologist, Jason Tomas, and a Dutch historian, Sonja Haas, are brought together by a professor of anthropology, a former Jewish exile, who is himself well informed on matters of spiritual history, including the views of Rudolf Steiner. Once the action moves to Europe—where sites relating to Almeida’s life and the Grail story are revisited—a Russian collector and Dutch educator enter the story to bring in more anthroposophical background.

The psychiatrist Laurence Oliver, a new spiritual source from South Africa with whom the author has been acquainted since 2004, has provided new and essential confirmation of Stein’s earlier claims. With his clairaudient faculties, Dr Oliver offered further karmic background to other events and personalities in western history—both before and since Almeida’s murder. His messages help to create a context to otherwise isolated pieces of information. Knot of Stone thus became a splendid example of a new genre—the karmic novel.

From a lecture by Nicolaas Vergunst at the Noord-Zuid Oost-West conference, hosted by the Stichtse Vrije School in Zeist, the Netherlands, on 11 June 2016. Several delegates share a link to Walter Johannes Stein, himself a Waldorf teacher in the 1920s, who relived the murder of Viceroy D’Almeida in a conscious dream. See comments below for more images from the author’s powerpoint presentation.

From a lecture by Nicolaas Vergunst at the Noord-Zuid Oost-West conference, hosted by the Stichtse Vrije School in Zeist, the Netherlands, on 11 June 2016. Several delegates share a link to Walter Johannes Stein, himself a Waldorf teacher in the 1920s, who relived the murder of Viceroy D’Almeida in a conscious dream. See comments below for more images from the author’s powerpoint presentation.

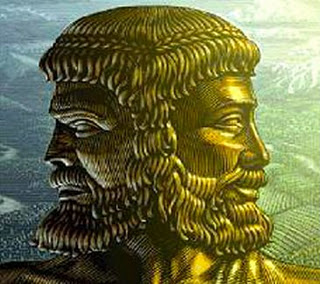

With more and more spiritual information becoming available since the beginning of the 20th century, books that elucidate spiritual history have become necessary. Stein himself, a man of deep spiritual insights, wrote such a book about the 9th century in relation to the Grail stories, commenting: “The history of the Grail is the history of the world. And the history of the world is the history of East and West.” (1928)

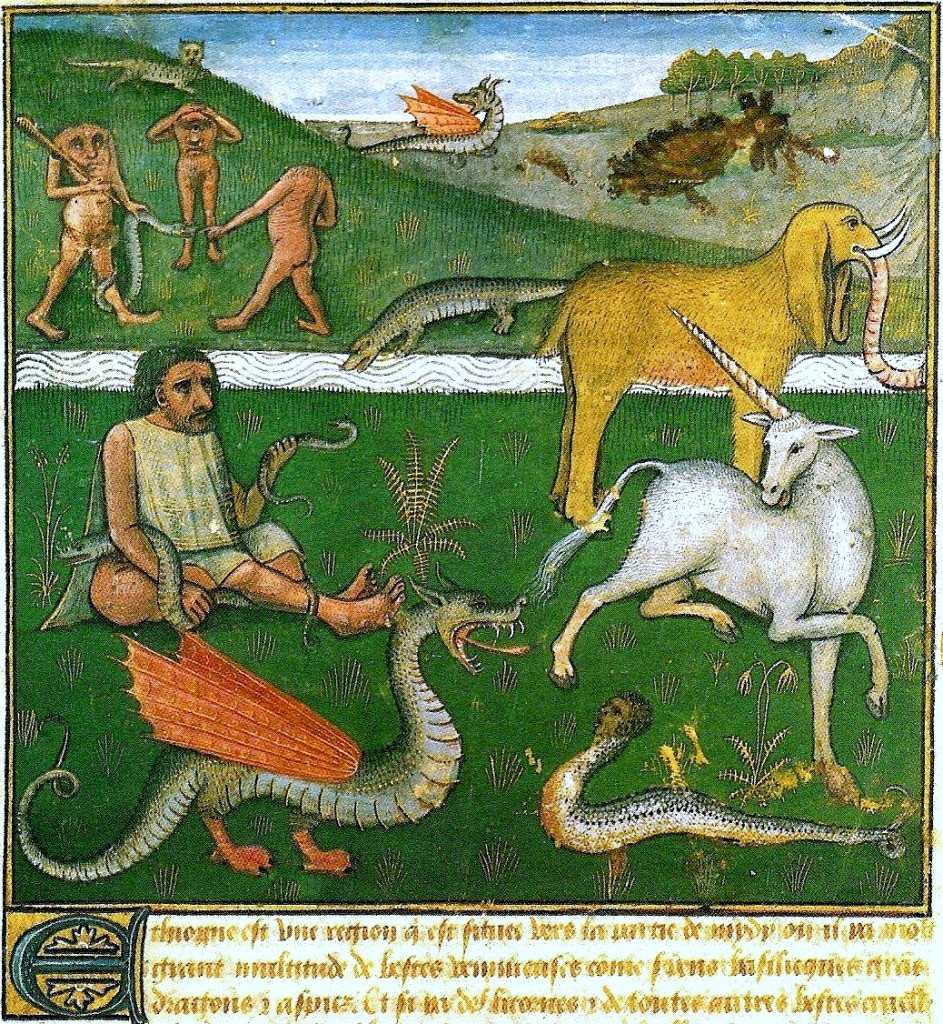

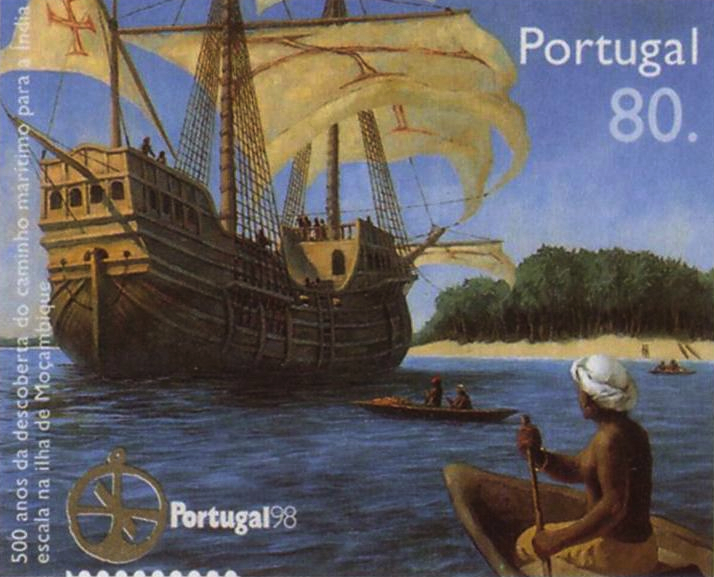

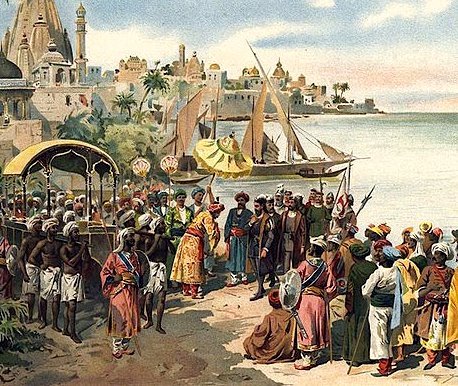

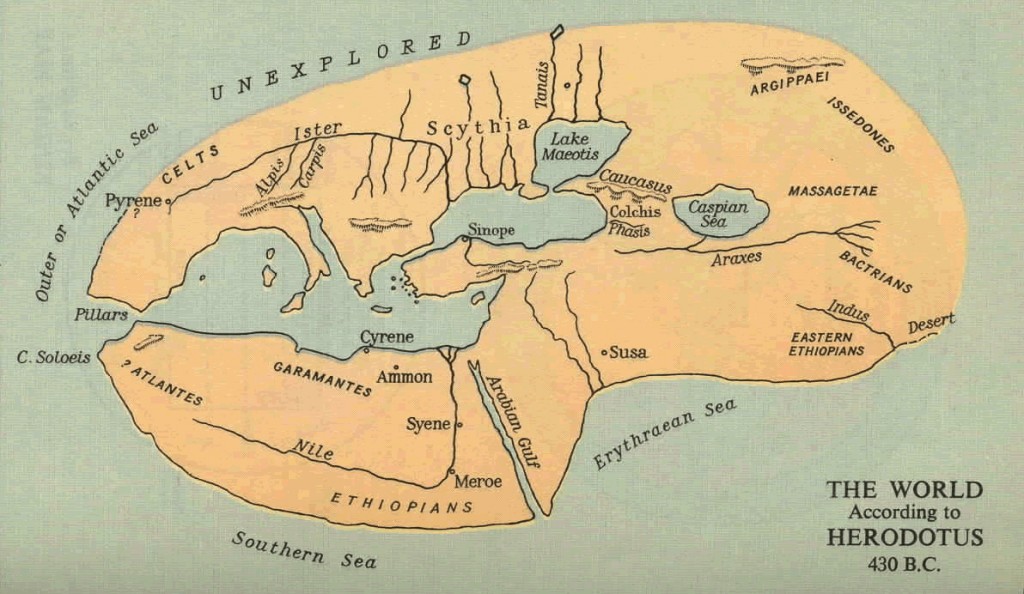

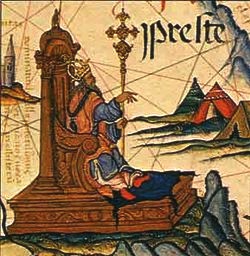

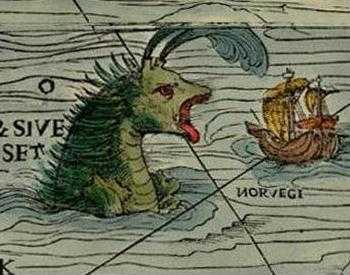

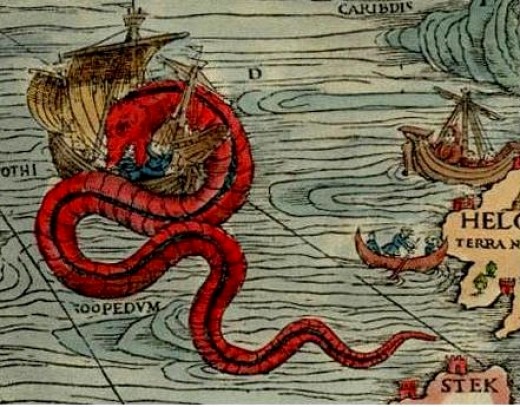

Stein often spoke about the polarity between East (Asia) and West (Europe), a polarity which permeates the Grail story of Wolfram von Eschenbach. The search for the kingdom of the enigmatic Prester John of India—known from the Grail story and from his mysterious letters—not only motivated the Portuguese discoveries of the 15th century, but lay behind Almeida’s secret mission in India. All this comes to new life in Knot of Stone.

From 1933, when he emigrated to England, and until his death in 1957, Stein played a prominent role in British Anthroposophy. He became well-known to the general public through the rather dubious books of Trevor Ravenscroft, in which he was to be featured posthumously. In Knot of Stone we meet Stein and some of his earlier incarnations again.

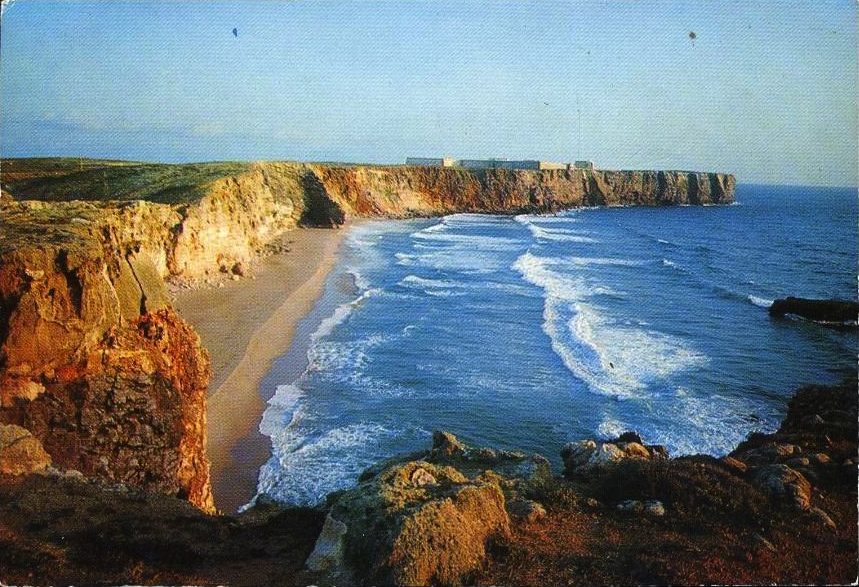

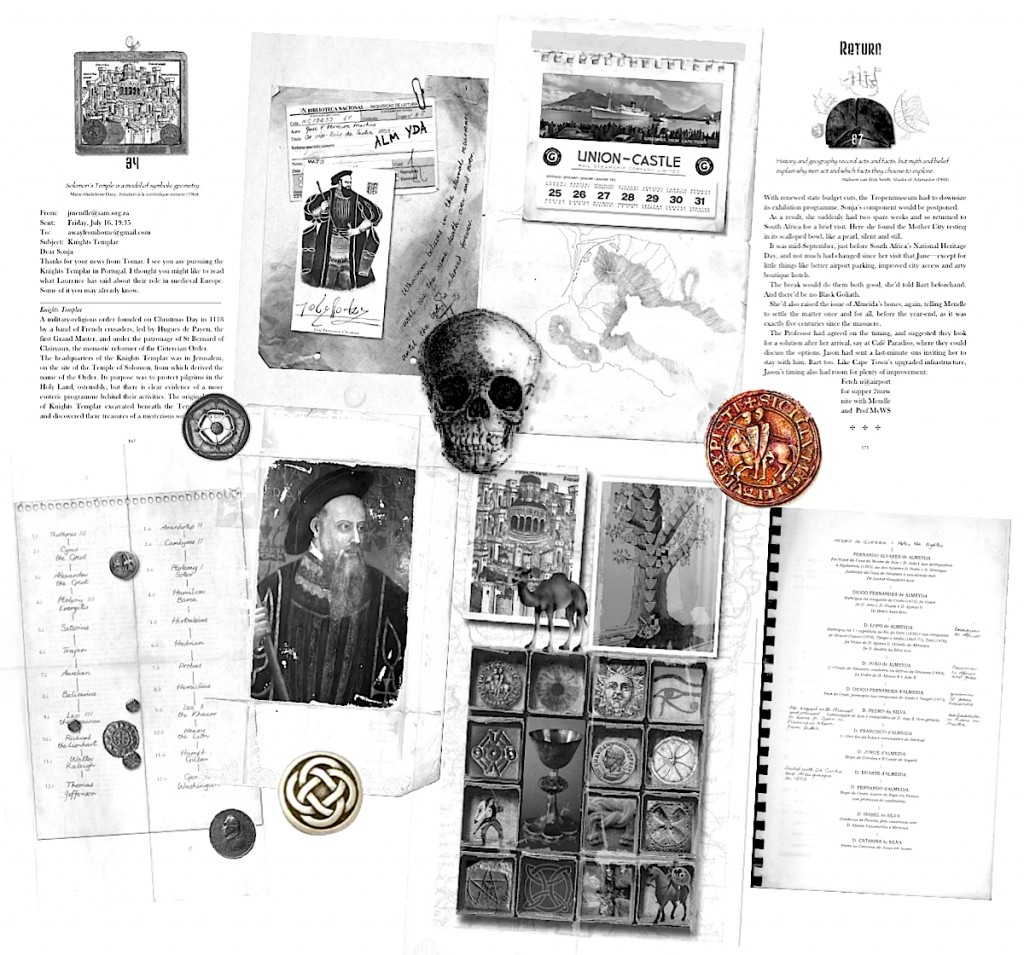

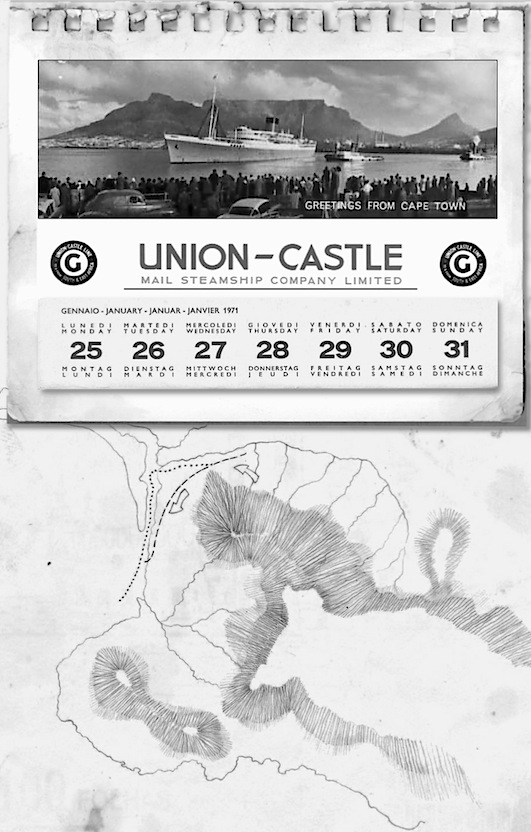

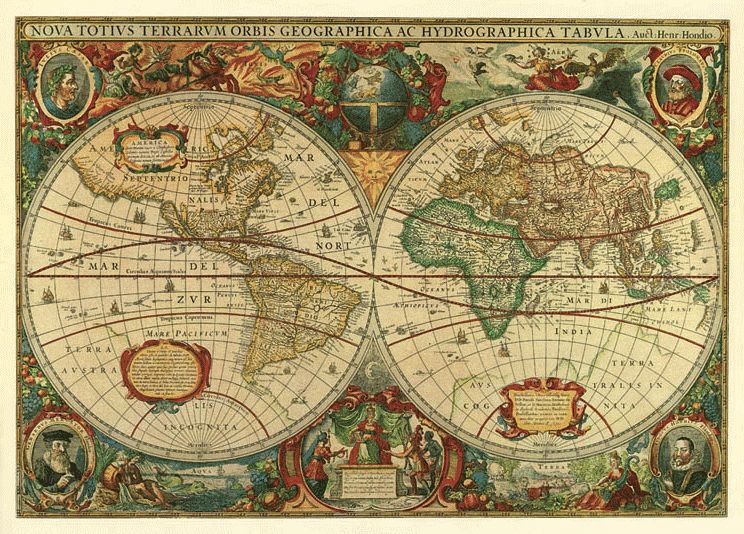

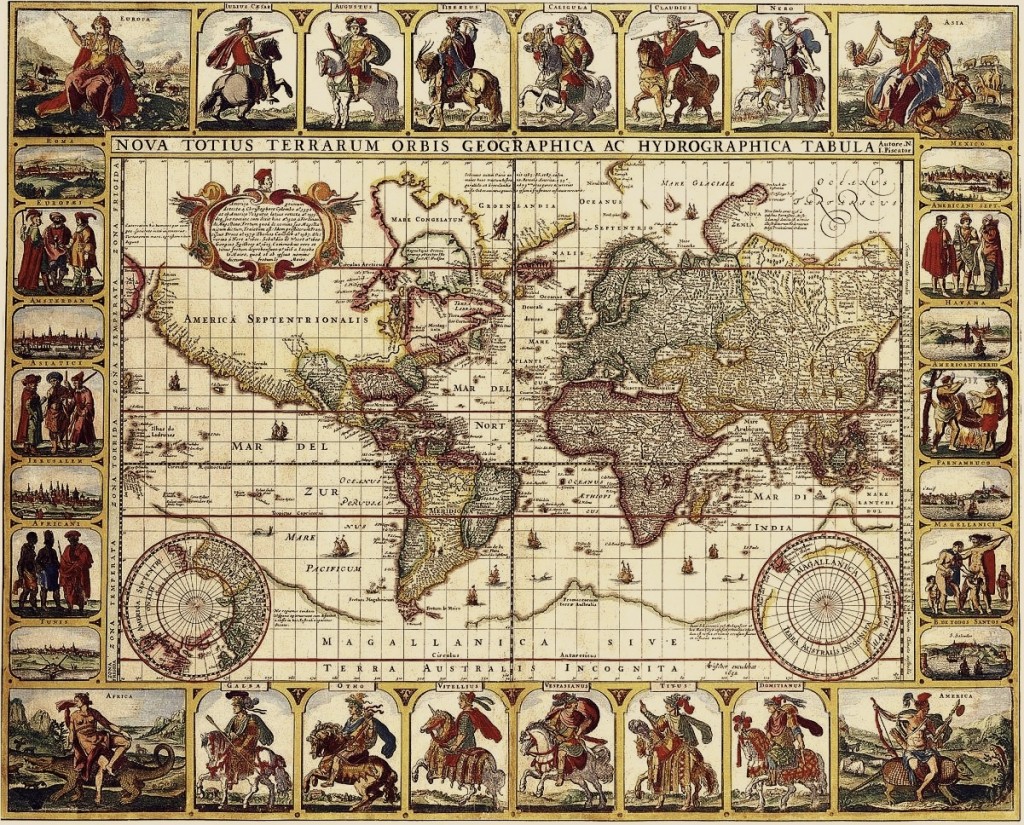

To propel his plot, Nicolaas Vergunst introduces a dossier containing crucial clues which assist the reader in his or her own quest. This dossier’s contents—articles, postcards, maps, handwritten notes and biographical lists—are interspersed throughout the text to produce a handsome publication of some 450 pages.

To propel his plot, Nicolaas Vergunst introduces a dossier containing crucial clues which assist the reader in his or her own quest. This dossier’s contents—articles, postcards, maps, handwritten notes and biographical lists—are interspersed throughout the text to produce a handsome publication of some 450 pages.

Central to Knot of Stone is the idea of the ‘eternal return’; namely, that we return to live again and again with the same friends, family and foes. This is demonstrated via several tabulated karmic biographies. The reader will certainly not take all the karmic information given in the book for granted. Also in this area of research mistakes can be made and people with clairvoyant or clairaudient faculties can be misled by spiritual beings trying to spread lies. For this reviewer, the information received by Dr Oliver (and presented in the book) about Jesus and Maria Magdalene having a son is a clear example of this phenomenon. As in all literature about spiritual matters, the readers are asked to develop their inner sense of truth.

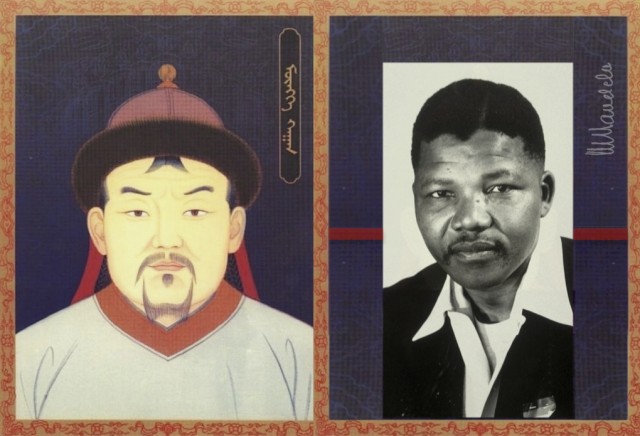

In the case of Almeida, the information about his karmic biography receives a clear context and thus makes sense to readers who wish to judge matters themselves. Other karmic biographies, however, such as those of Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Constantine, Charlemagne, Winston Churchill and Dag Hammarskjöld, miss such a context. They require further elaboration, a deeper understanding of karma, and confirmation from other sources, perhaps even another novel. To this end, the author is already preparing a sequel, Seeing Double: alternative portraits of history.

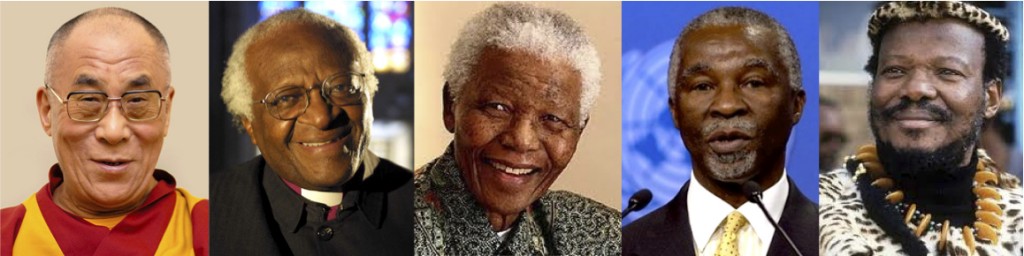

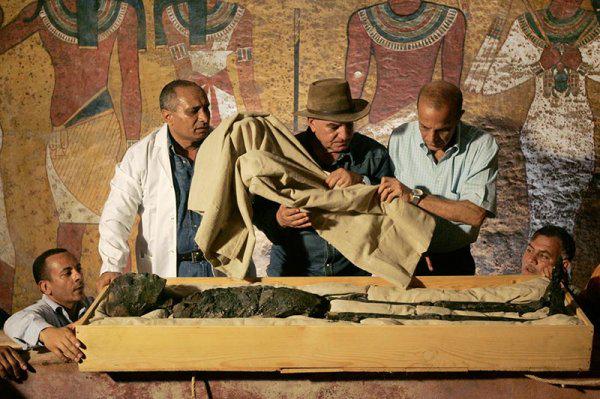

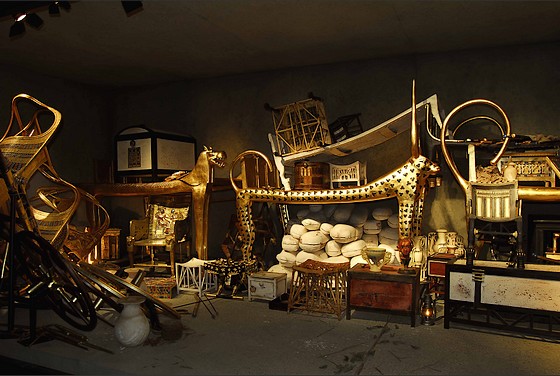

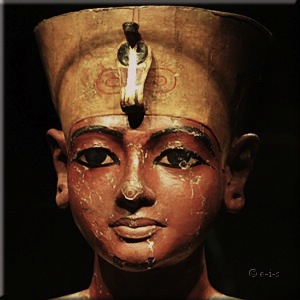

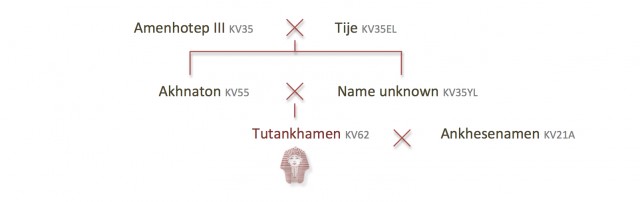

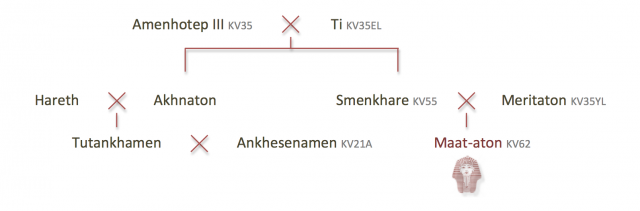

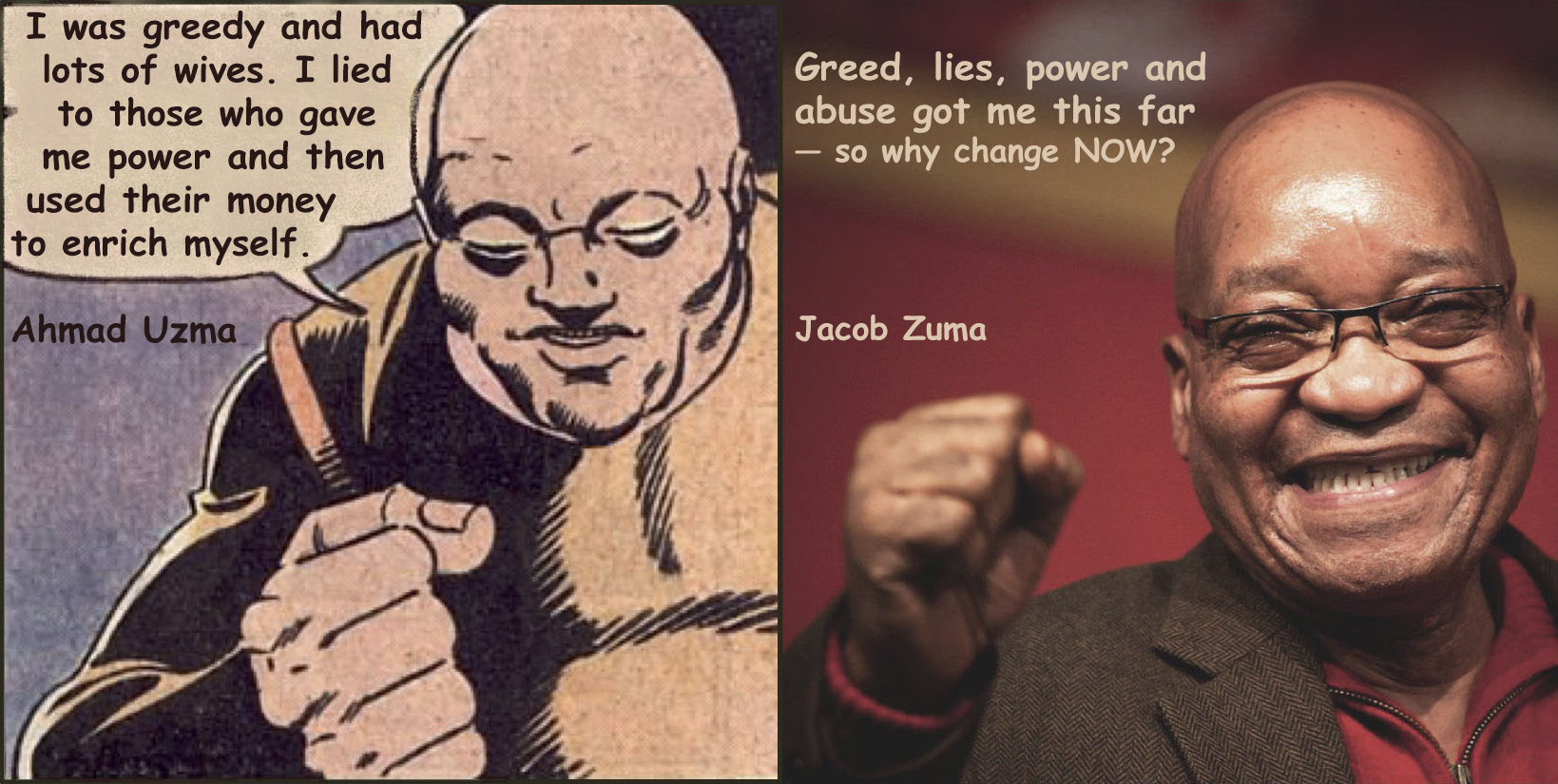

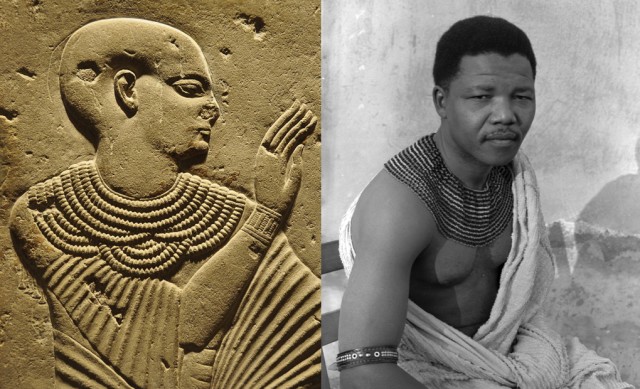

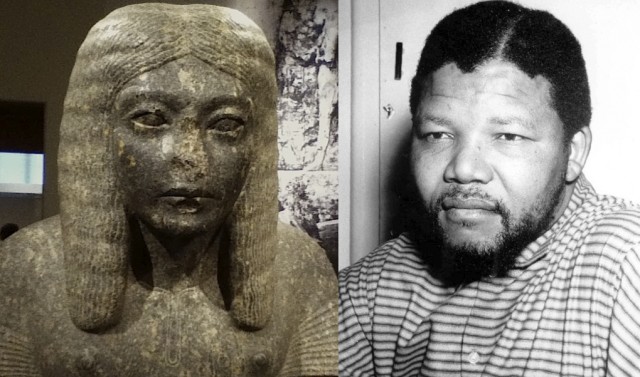

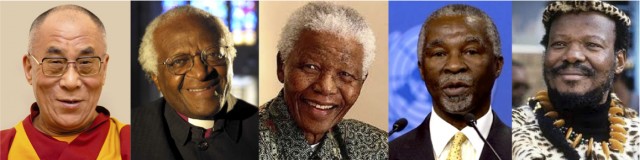

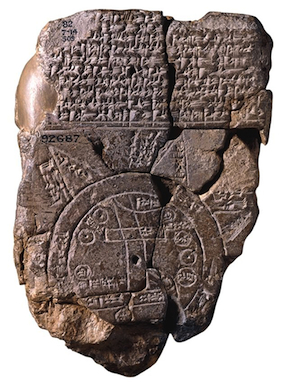

The bond between Ramaphosa and Zuma can be traced back to ancient Egypt, c.1300BCE,

The bond between Ramaphosa and Zuma can be traced back to ancient Egypt, c.1300BCE,  How are we to remember

How are we to remember

This old Volvo coupé is the one used by Sonja and Jason in

This old Volvo coupé is the one used by Sonja and Jason in