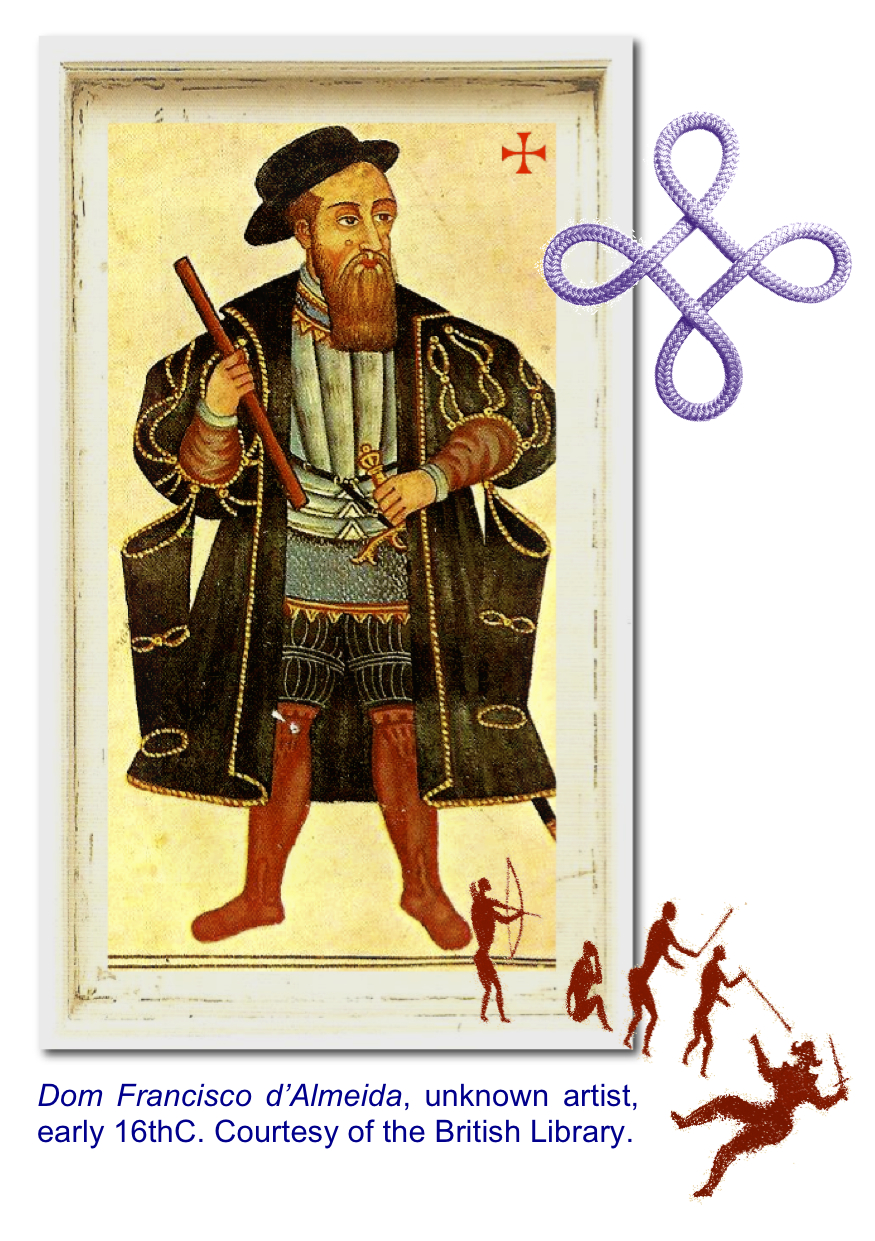

Video cover image: ‘The massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, 1510’

by Angus McBride, 1984.

Knot of Stone is a unique historical novel that begins and ends with an enigma—an alleged mass murder in South Africa and a long-lost treatise, the Sierra Nevada. In 1510, when the Cape of Good Hope was still revered as a southern Portal to the Indies, the Viceroy of Portuguese India was led ashore, attacked, slain and hurriedly buried in a shallow grave. The death of Francisco d’Almeida and sixty-odd compatriots remains a mystery to this day. Was it the fulfillment of a prophecy or an act of poetic justice? Was it an ambush, a mutiny or even an assassination? And if so, was it instigated by Manuel I, then king of Portugal, or by a secret cabal within the Church of Rome?

Knot of Stone is a unique historical novel that begins and ends with an enigma—an alleged mass murder in South Africa and a long-lost treatise, the Sierra Nevada. In 1510, when the Cape of Good Hope was still revered as a southern Portal to the Indies, the Viceroy of Portuguese India was led ashore, attacked, slain and hurriedly buried in a shallow grave. The death of Francisco d’Almeida and sixty-odd compatriots remains a mystery to this day. Was it the fulfillment of a prophecy or an act of poetic justice? Was it an ambush, a mutiny or even an assassination? And if so, was it instigated by Manuel I, then king of Portugal, or by a secret cabal within the Church of Rome?

What is this book about?

At the heart of Knot of Stone is the concept of the eternal return; namely, that we live again and again with the same family, friends and foes. While the book provides ample biographical background, it is only when the protagonists reach the limits of their historical research that the karmic biographies of historical figures are introduced to help explain events and their outcomes.

Knot of Stone is a multilayered work with a complex plot; incorporating recorded histories, official documents, private diary notes, oral testimonies, dreams and prophecies. The story is divided into eight sequential sections—Arrival, Journey, Departure, Travel, Home, Digression, Alignment, Return —and includes a hundred illustrations, numerous emails and skype exchanges, as well as the actual messages from a clairaudient sangoma (traditionally, a healer empowered by the ancestors). The author designed and illustrated his novel and is currently producing an e-edition for release in 2015.

Now read the first chapters free!

“The killing of Almeida is one of the greatest tragedies in Portuguese history.” Victor de Kock, chief archivist, Cape Town, 1952.

“The killing of Almeida was our finest hour and gives us pride of place in modern history.” Ron Martin, Khoisan community leader, Cape Town, 2010.

Our finest hour or greatest tragedy?

This violent clash took place in 1510, when Dom Francisco de Almeida (Viceroy and Governor of the Portuguese State in India) went ashore. He apparently angered the Khoi-Khoi because he approached one of their settlements uninvited. Some of his marines were injured in a skirmish. In retaliation about 100 of his men returned and took some cattle and a few children as hostages.

However, the Portuguese found themselves suddenly surrounded by a large herd of cattle, driven by the Khoi—who then threw fire-hardened, wooden spears at them from behind this moving “defensive wall.” The marines had neglected to wear armor, and carried only swords, so they could not effectively defend themselves, and de Almeida and 58 of his men were killed by being speared, or trampled by the cattle. Thereafter, the Portuguese largely avoided the Cape.

Thanks for this vivid description, Cuan, though I’m not sure of any “uninvited” visit? It was a punitive expedition which Almeida himself led, reluctantly, after several officers voted in favour of reprisals and a pre-dawn raid on the village. Almeida and those faithful to him suspected foul play and, indeed, were led into an ambush by a faction among his crew. The confrontation was orchestrated to look like the fulfillment of the famed witches prophecy that “Ameida would not pass beyond the Cape of Good Hope, it being the portal to the Estado da Índia and the border of his realm”.

See Knot of Stone (pp.81–82) for a more detailed reconstruction of events that fateful Friday morning.

A very accurate description as well… thanks for the memory, guys.

“The killing of Almeida was our finest hour and gives us pride of place in modern history.” Stick by your anniversary comment, Ron, that’s fine with me, but don’t take on the burden of blame for this massacre. Your forebearers were set up to attack Almeida while his true assassins abandoned him, so that history would remember the Cape Khoisan as a wild and unreliable lot. Portugal’s propaganda worked and has been repeated for five hundred years. Now is the time to reclaim your peoples’ role in saving southern Africa from a very different future—that is, from becoming a second Brazil. See my blog on why South Africa isn’t Brazil

I don’t think that my people would regard the actions of our forebears on that fateful day as a “burden of blame”… remember, too, that the various accounts of the event were all recorded and intepreted from various biased opinions (ours too, for that matter), and that the debate is finally raging, as it should have a long time ago. History as a discipline may very well be the winner in the end.

You were blamed, however, by Portuguese chroniclers. Unwitting or not, they drew attention away from the actual conspirators in Lisbon and Cochin, India.

I realise that, but in the context of the day, the Goringhaiqua perceived the visitors as intruders whom they had to dispel since they (the Portuguese) made the first threatening gestures. The Khoi would not have been interested in any conspiracy… it was not their business. Even today, the attitude amongst our people with regard to the Portuguese chroniclers’ accounts are “so what?”

Last year we celebrated the 500-year anniversary of a victory in a David and Goliath-type battle against a (superior) evil slave-trader and war-monger, and it is simply this vision that instills in our people a pride that is incomparable with any other, especially when our nation is starving for heroes and pride in our heritage. As much as there is truth, blame, interpretation, conspiracy-theories out there, our people are resolute: the Goringhaiqua kicked D’Almeida’s ass! He may have sacked Sofia and brought down the Ottoman Empire, but a few lowly pastoralists saw the end of him. Grant us that, at least.

You killed him, granted, with a sling-shot stone behind his knee and a wooden spear through his throat. You can make of that what you will, Ron, but to my mind it was a heroic victory in defense of all that was dear to you: your women, your children and your cattle. But this is not my point. I merely wish to state that Almeida was the true victim here; the victim of an order of execution disguised as a prophecy of doom. According to the clairaudient message cited in my book:

“The Viceroy was already dead, and his party wiped out, when the conspirators returned to seal their atrocity—ritually piercing Almeida through the throat with a lance of steel. Thus they silenced him forever.” (KoS p.13)

Could you, as the Silent Ones who have suffered through our history, perhaps speak for him too?

As a student of history, I would not completely discount the idea of redressing the historical narrative by speaking for D’Almeida too. However, that is the very point. We, the Khoi-khoi and Boesman (we hate the term Khoisan, by the way), find ourselves constantly having to scream to be heard, and then still get ignored, so why should we speak for a perpetrator of violence against us, even if it merely serves to complete the narrative? Nobody is prepared to do that for us.

Maybe, after a few more years, when our own pain is somewhat less, we can entertain the notion, but at the moment we are still trying to enter our narrative into the frey, against all odds… charity begins at home.

While we clearly differ on the character of Almeida and the role played by his own men in the ambush—including their ritual killing of him afterwards—the event marks the first recorded battle and first known murder in South African history. I wish you well with your narrative, Ron, and hope your voice is heard.

The first known murder in South Africa’s history? Really? I mean… really?

It’s the earliest recorded murder we have. There were others before, of course, but these haven’t survived on record or in local oral tradition. If you know of one that predates this first encounter at the Cape, then please do pass it on Malcolm.

It seems the San or Boesman are the tree with many branches of humanity, not only in Africa, but everywhere. I think that’s why the Europeans went to Africa, after the Arabs did, they went to meet their ancestors. Excuse my expression in English, it is not good, I’m Portuguese.

Isabel, your English is fine and far better than my poor Portuguese. I had to ask others to translate key texts during my research. Triste.

You raise a significant point about the origins of Arabian and European expansion in Africa. While the need for trade, territory and converts played a part, men like Almeida used this opportunity to re-establish contact with pre-Muslim and pre-Christian forms of worship—that is, with the so-called Wisdom of the Ancients.

It is curious that you should raise this, now, as it was the main motive behind Almeida’s execution. He was in fact silenced after death (his tongue was removed) for trying to re-open channels of esoteric communication between East and West. Please see my article on rethinking east-west histories.