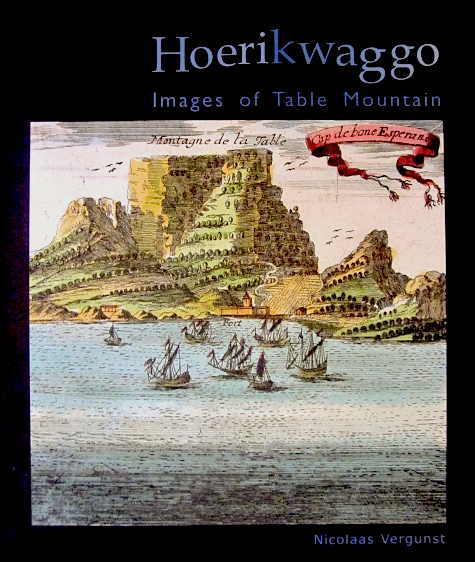

Produced for a landmark exhibition at the SA National Gallery in 2000, Hoerikwaggo brings together the best maps, travel journals, colonial prints, paintings, photographs and postcards of Table Mountain. It also shows how the legendary Mountain of the Sea—once seen as crude and barbaric—became the most popular symbol in a new democratic South Africa. The imagery serves here as a unique leitmotif for Knot of Stone. Soft cover 96pp. ISBN 1-874817-27-8

Produced for a landmark exhibition at the SA National Gallery in 2000, Hoerikwaggo brings together the best maps, travel journals, colonial prints, paintings, photographs and postcards of Table Mountain. It also shows how the legendary Mountain of the Sea—once seen as crude and barbaric—became the most popular symbol in a new democratic South Africa. The imagery serves here as a unique leitmotif for Knot of Stone. Soft cover 96pp. ISBN 1-874817-27-8

Online version, presented at the SA Museums Association Conference, 2000: Table of the Cape, Mountain of the Sea

Portal to the Indies

For bygone centuries the Cape of Good Hope was seen as the southernmost Portal to the Indies, and known as the most dangerous ocean crossing in the world. Situated at the farthest end of the African continent, the rugged promontory jutted out into the Atlantic and Indian oceans. Ironically, this peninsula is known as the Fairest Cape today.

Besides its unmistakable steep face and flat summit, most artists emphasized the mountain’s height as its most obvious natural feature. Not only was the mountain an impressive sight when compared to low-lying Dutch and English landscapes, but the beach was then closer to the mountain and hence seemed much higher than it does today. The sea has since been pushed back several hundred metres.

The Adamastor legend

The Adamastor legend

Towering above modern Cape Town, Table Mountain seemed to personify the character of a Stormy Cape. The mountain was a wild and vindictive giant called Adamastor, a tormented figure from Greek mythology, who dashed the hopes of passing mortals. The Cape was his forbidden portal, beyond which neither ship nor sail should pass.

The long voyage East, amid raging storms and inner temptations, symbolized a journey of spiritual enlightenment. It was a concept that possessed Prince Henry and the explorers of Atlantic-Africa, a concept that also transformed the ‘Discoveries’ into a quest for individual spiritual enlightenment. Portugal’s exploration from West Africa to East Africa, from the shores of the Atlantic to the Indian seaboard, was thus more than a mere adventure in maritime geography. And so in 1488 a weatherworn Bartolomeu Dias first crossed this great divide, unknowingly, after being driven out to sea by a raging storm.

Artist’s impression of the giant Adamastor, showing the Portuguese fleet rounding the Cape of Good Hope. Courtesy Marina dos Santos Salgueirio Tomas Teixeira.

Artist’s impression of the giant Adamastor, showing the Portuguese fleet rounding the Cape of Good Hope. Courtesy Marina dos Santos Salgueirio Tomas Teixeira.

A decade later, on his historic outbound voyage to India in 1497, Vasco da Gama too clashed with Adamastor off the Cape. Their confrontation came to symbolise the conflict between modern man and the classical gods. For Luís de Camões, poet laureate of Portugal, the clash symbolised mankind’s inevitable triumph over the gods, a triumph of the Renaissance over the Medieval, of humanism over dogmatism.

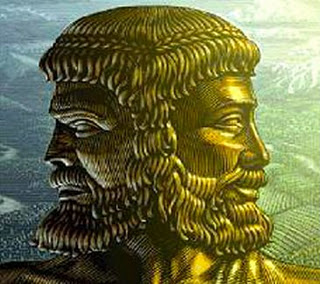

The symbol of Janus

Table Mountain has also been likened to the double-headed god Janus of mythology. Looking forward and back, he was a most awe inspiring Door- or Gate Keeper. Janus looks ahead and behind, knowing the future as well as the past. Likewise, Table Mountain watched over the African continent, protecting it from men sailing across the Atlantic and into the Indian Ocean, West to East, new to old, cold to warm.

The double-headed Janus (left and right), Rome’s ancient god of exits, of transitions and of new beginnings.

The double-headed Janus (left and right), Rome’s ancient god of exits, of transitions and of new beginnings.

Background photograph of Table Mountain (excluding African figurine) by Mark Skinner, c.1998.

Background photograph of Table Mountain (excluding African figurine) by Mark Skinner, c.1998.

A Southern Paradise

Dante invoked the Ptolemaic tradition of a southern paradise when he placed his island of Purgatory off to the South, with Titans guarding the watery transit to Paradiso. Dante’s Divine Comedy describes Paradiso as a mountain surrounded by forest from which two streams flowed. The undaunted Ulysses sailed for five months until, under the stars of the southern pole, he suddenly saw “a mountain obscured by distance and of a height never seen before”. It was his imagery that inspired Camões and, over time, Ptolemy’s legendary Mountains of the Moon were displaced further and further south until they formed the barrier range around South Africa. Over the next few centuries, c.1300–1500, Ptolemy’s Mountains of the Moon and Dante’s Mountains of the Sea came to be associated with Table Mountain. In short, Table Mountain was imagined before it was seen by European seafarers.

Cyril Coetzee, Ship of Fools, 1992, oil on canvas. The artist’s self-portrait as Dante suggests an intimate identification with the process of Christian initiation. The subtle depiction of Table Mountain on the horizon signifies the pilgrim’s physical journey and, simultaneously, the initiates spiritual journey to Paradiso.

Cyril Coetzee, Ship of Fools, 1992, oil on canvas. The artist’s self-portrait as Dante suggests an intimate identification with the process of Christian initiation. The subtle depiction of Table Mountain on the horizon signifies the pilgrim’s physical journey and, simultaneously, the initiates spiritual journey to Paradiso.

Other identifications

Table Mountain has been known by various names: Hoerikwaggo (Mountain of the Sea), //Hû!Gâis (Great Rocks of Storms), Unlindi Wemingizimu (Watcher of the South) and Adamastor (Untamed). It has also been called d’Klipman (Stone Man), the Old Grey Father and the Thrice-Great Mother. In her poem, The Spell of Table Mountain, c.193o, Marion de Beer praises the mountain, saying: “O Guardian of the City by the Sea… Great Janus of the Southern Seas”.

‘Table Mountain with Tea Cup’ by Wayne Coughlan, digitally enhanced photograph, 1999.

‘Table Mountain with Tea Cup’ by Wayne Coughlan, digitally enhanced photograph, 1999.

While the Dutch called the mountain’s cloud a “tablecloth”, the French described it as a “wig”. According to the indigenous San (Bushman), the cloth belongs to their god Mantis who threw his huge white karos (sheep pelt) over the summit to prevent summer veld fires. Others says the cloud comes from a smoking contest between a Dutch pirate, known as Van Hunks, and the Devil. In a Faustian-like duel, this vagabond-hero was willing to sell his soul in order to control the forces of nature. It seems the Cape Muslims used (started?) this story to symbolise the vanities of a foolish foreigner. Lady Anne Barnard, one of the Cape’s most famous English visitors, compared the cloudy cloth to “a fine damask” and described it as “a necklace of vapours that circles the Mountain’s great throat”. These metaphors reinforce two common associations—first as a table and secondly as a giant.

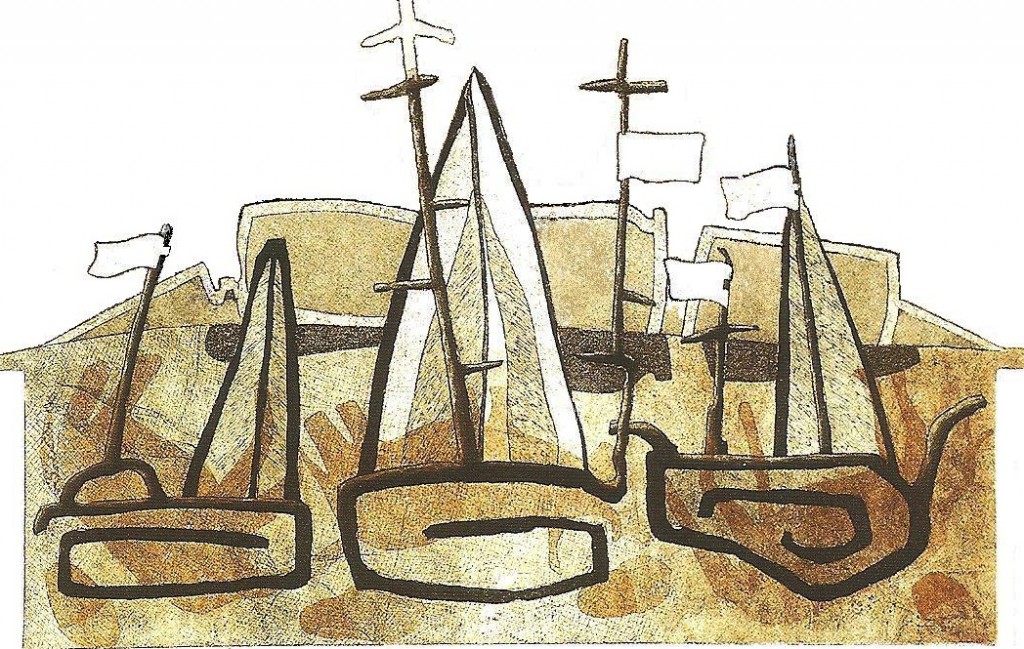

‘For Dia!kwain’ by Pippa Skotnes, South Africa 1993, coloured etching. Dia!Kwain was a San prisoner at the Breakwater Convict Station, Cape Town c.1870.

‘For Dia!kwain’ by Pippa Skotnes, South Africa 1993, coloured etching. Dia!Kwain was a San prisoner at the Breakwater Convict Station, Cape Town c.1870.

The distinctive profile of Table Mountain is just visible behind these three sailing ships. When Almeida touched at the Cape in 1510, a century before the first Dutch and English fleets, he too arrived with three ships.

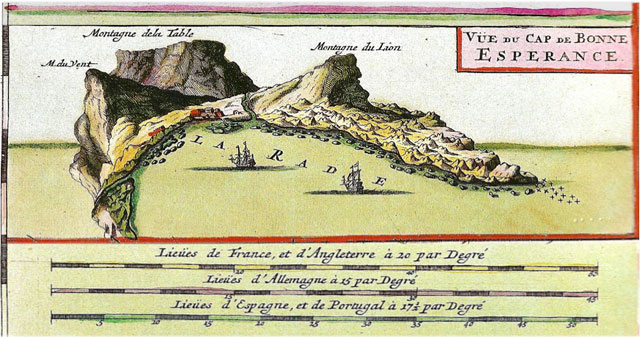

‘Vue de Cap de Bonne Esperance’, inset from Simon de la Loubère’s Du Royaume de Siam, French, 1691.

‘Vue de Cap de Bonne Esperance’, inset from Simon de la Loubère’s Du Royaume de Siam, French, 1691.

Mountain of the Sea

This extraordinary view of Table Mountain depicts the mountain as a separate, isolated entity surounded by sea. At the time efforts were made to dig a canal from Table Bay to False Bay (see inset bottom left), to cut the Peninsula off from the Flats—somewhat like a moat does around a castle. The project was aborted after the canal kept filling in with sand. Table Mountain was known by local herders as Hoerikwaggo or, quite literally, as the Mountain of the Sea. This line (approximate with the railway between Cape Town and Muizenberg) still separates the Peninsula from the Cape Flats. The ill-fated Battle of Gorinhaiqua took place on the beach below Devil’s Peak (seen also at bottom left).

This over-simplified rendering of Table Mountain shows a former, more intimate relationship between the mountain and the sea. The relationship changed dramatically with the land reclamation and new harbour project of the early 1900s—and the first relocation of Cape Town’s black populace—during which time the grave of Almeida and his men was unknowingly covered by tons of landfill. Since then the sea itself has been pushed back one kilometre.

This over-simplified rendering of Table Mountain shows a former, more intimate relationship between the mountain and the sea. The relationship changed dramatically with the land reclamation and new harbour project of the early 1900s—and the first relocation of Cape Town’s black populace—during which time the grave of Almeida and his men was unknowingly covered by tons of landfill. Since then the sea itself has been pushed back one kilometre.

Table Mountain, Nicolas Maritz, 1991, enamel paint.

‘Greetings from Cape Town.’ A trip to South Africa promised to be an ideal holiday. Postcard c.1960.

‘Greetings from Cape Town.’ A trip to South Africa promised to be an ideal holiday. Postcard c.1960.

Inspirations

Twentieth-century tourists visiting Cape Town were offered a Mediterranean haven for bathing, fishing, climbing, motoring and, of course, symphony concerts. In the two post-war images above, Table Mountain (with Devil’s Peak on the far left) is shown as it may have appeared that fateful summer morning when Almeida was ambushed. See our book release video (below left) or watch the music video (below right) for more mountain images—and the most beautiful Afrikaans song ever. Courtesy of Dozi and Koos Kombuis.

What do you think of Cape Town’s honourary new name: //Hui !Gaeb, literally “where the clouds gather”?

I noted the name as //Hû!Gâis or “Great Rocks of Storms” in Hoerikwaggo: Images of Table Mountain. Is there a preferred spelling and/or translation?

No matter what language a tourist speaks, I guess most will find //Hui !Gaeb impossible to pronounce, nor know where it is whenever the name appears on Arrival/Departure boards at international airports.

As a tour operator in South Africa, I just want you to know how frequently I refer to your Hoerikwaggo publication and show its images to visitors. The book is a constant source of inspiration and I wish the exhibition were a permanent part of Iziko Museums in Cape Town. So thank you for leaving us a mind-shifting legacy!