‘You saw the executioner,’ blurted Sonja over the phone, ‘we both know he aimed for the throat.’

→Jason remained silent, the webcam’s impassive eye monitoring each gesture in halted steps: his shrugging shoulders, the averted gaze, a face pinched with jaundice

→Sonja could still see the mountain’s sombre silhouette behind him. Table Mountain slumbered: long, low and unmistakably flat.

→Back in Leiden it was cold and dark.

→‘Can you hear?’

→She fiddled with the Skype settings.

→His reply was terse: ‘Sure, and see you too.’

→They knew it was staged to look like an error of judgement, a freak accident, one which none were prepared for yet everyone expected. After all, it had been predicted and, uncannily, like the prophecy itself, the message was explicit.

→Now she’d received another.

→‘It says we were both there, Jason, together.’

→‘Nonsense!’

→‘Well, you asked me. D’you want to know or not?’

→He hesitated. So much had happened to them in six months—and now this?

→‘Dunno. I don’t recall anything, no ritual killing at all.’

→His indifference was all too familiar.

→She continued impatiently:

→‘The new message says we saw what happened, hiding in the dunes. Don’t you think that’s reason enough to know if—?’

→‘—if it really happened?’

→He shrugged again, the blurred transmission exaggerating his face.

→‘Then why don’t I remember anything?’

→Silence. She lent in:

→‘Hey, I’ve asked myself that too, over and over, ever since we found that damn skeleton…’

→Her retort was unnecessarily sharp. She should apologise, but her focus shifted as yet one more email popped up on her screen.

→‘Wait, I’ll skype you back later.’

→She hung up and opened her inbox. It was Thursday 16 December, the Day of Reconciliation in South Africa.

→

→

→

The infamous Cape of Storms was no myth. Sonja had witnessed its wrath half a year ago, when north-westerly gales and torrential rains battered the Peninsula. It was already the second week in June and she’d seen a heavy swell roll on the horizon, a tumultuous sea surge into the bay and windswept waves pound the beach below Table Mountain. It was a winter’s tempest, a real Adamastorm.

→Once it cleared, a jubilant sun vaulted over the Bergen van Afrika while the moon’s disc dipped into the bay. Sonja was out for a brisk walk beneath the mountain’s brow and, catching her breath, peered at the glistening city below.

→Cape Town lay in its scalloped bowl, like a pearl, silent and still. It was the gem of a bygone era and the crown jewel of a former empire. It was the seafarer’s Tavern of the Seas, a colonial Gateway to Africa, and the Mother City for generations of white South Africans.

→Looking toward the city-centre she saw the Company’s Gardens with its tree-lined avenues, ornamental lawns and formal footpaths—including the old white-washed Slave Lodge at the lower-end of the gardens. One by one she singled out the other buildings: parliament, the library, the national gallery and national museum. The last was easy to recognise with its conspicuous copper-domed planetarium.

→Here, as Head of Anthropology, her hiking companion had spent the last three decades examining pre-settlement cultures at the Cape.

→Professor Joshua E Mendle was a man with a flare for largesse, for grand gestures and, from his mother’s side, endowed with an erudite mind. In appearance he was all too large for life. His enquiring nose bent against the breeze, his beard parted like a bow wave across his chest and, under a balding forehead, his eyebrows struck Sonja as the bushiest she’d ever seen. Blowing his hands for warmth, he resembled the vagabond pirate of local mountain legend.

→Sonja and he nestled in a deep gorge used for reaching the summit. The first recorded ascent was made by Portuguese seafarers who—as hunter-gatherers had done for generations—climbed the same route to espy the environs. The interlopers were lost, Mendle explained, and from high above the Land of the Red People they offered their prayers while the gods of the Quena-ku whispered back on the wind.

→No doubt the young men enjoyed the exercise too.

→Not so the ageing professor who, catching his breath, spoke slowly:

→‘All roads lead to Rome, even caravan routes for circus animals, which is why old Pliny said: “Out of Africa always something new”. Now taste our spring, it doesn’t get any better, only in Paradise!’

→He lent forward and cupped his hands, drawing a mouthful of clear water. It was cold and sweet. Though stiff, his body felt refreshed.

→‘Bedankt, but I have my own,’ said Sonja, delving into her bag for the bottle she always carried with her.

→Mendle was visibly disappointed. She’d declined the best he had to offer, even during the driest months of the year. It was a little miracle in his paradise, where the source literally flowed from the rock.

→Sitting beside him, she swung her legs over the ledge, surprised how heavy her boots now were. She wore splash covers to keep her socks dry and woollen mittens against the chill. She leant in to retrieve the bottled water, her Persols dropping loose on their strap.

→‘With respect, Prof, it sounds like a conspiracy when it was merely an accident of history, a fortunate mistake, really, as the Dutch only set up a refreshment station after they’d been shipwrecked here. They never planned to settle, not permanently, no, as they far preferred Mozambique with its foot in East Africa’s infrastructure. They even tried taking the island, twice, but the Portuguese beat them back.’

→‘True, had the Portuguese clung to the Cape the outcome could’ve been very different. South Africa would be another Brazil. We’d be Catholic and eating a lot more rice and beans. Oi-vey, how different!’

→‘How so,’ she teased, twirling her bottle, ‘whether Portuguese or Dutch, the natives would still be buried in a Christian graveyard?’

→‘Ah, master and slave, side by side,’ he said with a raised eyebrow, ‘including those who could conceal their traditional beliefs. Some had gold coins put over their eyes, as was common for the time, yet kept symbols of ancestral worship hidden under their clothes.’

→‘They were laid facing up?’

→‘Yes, but not the indigenes. They were buried in a seated position. Their remains are often exposed when storms gnaw at the hardened dunes along the beach,’ he paused, wiping his wet brow with a sleeve. ‘The unconverted were taken to a site farther away. The city is built on isolated burial sites that once surrounded Cape Town.’

→‘Isolated cemeteries and hospitals are a consequence of hygiene and wealth,’ she noted pragmatically, ‘like the old isola Tiberina of Rome. Moreover, the rich have always enjoyed better sanitation, better food, and the best cosmetics or medicine money could buy. Personally, I can’t imagine life without flushing toilets, hot baths or clean sheets…’

→Her gentle smile, Etruscan-like, evoked memories of his late wife.

→‘We all die in the end,’ he replied, his face now drawn with sorrow.

→For a minute neither spoke. They looked toward the Waterfront where, several years earlier, he’d uncovered a thousand skeletons: adults, infants and the elderly; slaves and free citizens; Europeans, Asians and Africans—including those born at the Cape itself.

→As the SA Museum’s senior anthropologist he’d supervised the dig amid much debate in the press. He was accustomed to controversy.

→His career had been marred by Apartheid authorities and the new bureaucrats of democracy. While some had welcomed arguments for pre-settlement encounters, others now denied any foreign contact. He was among the few independent academics still prepared to challenge notions of origins, ownership and inheritance in southern Africa.

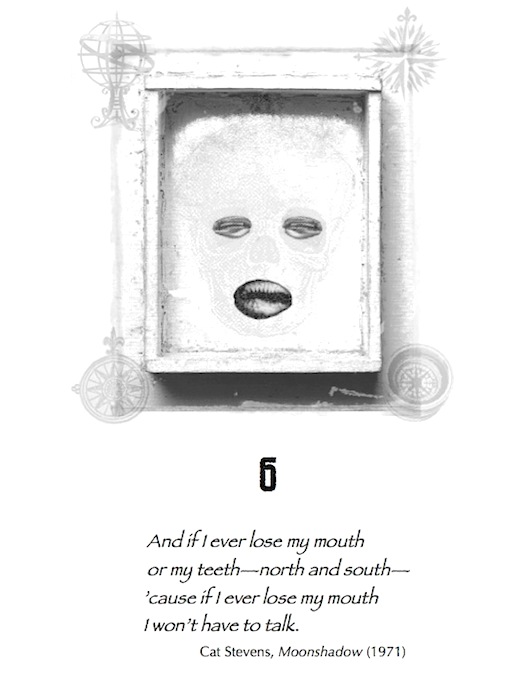

→‘There were originally two cemeteries: a site for Christians and an unmarked one for pagans, slaves, and those unable to pay the grave-diggers’ fee. In the first we found a slave girl with a pendant around her neck—a tiny carved idol made of cowry shell. We suspect she was a heathen at heart when she died.’

→‘Perhaps,’ suggested Sonja carefully, ‘perhaps symbols and pagan rituals were tolerated as long as Christian beliefs weren’t threatened. Or concealed, as Jews had to do in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.’

→‘Or, as we did here, initially. Lutherans too. We weren’t allowed to display signs of worship outside our homes. Nor allowed to have our own church or synagogue.’

→‘Y’know, today, in Amsterdam, they say Sinterklaas can’t parade with a cross on his mitre as it may offend others.’

→Again neither spoke, taking in the view of the Mother City resting in the crook of the mountain’s arm. The foreshore lay open to the Atlantic, a restless silver-green, as the Indian sprawled away, unseen, behind the mountain.

→Out to sea the occidental and oriental currents collided: one born among Antarctic icebergs, the other coming from Equatorial waters. The upwelling, salt-laden Atlantic lumbered up the barren west coast while the shallow Indian swept down the lush eastern seaboard.

→Over the millennia the cold Benguela and tropical Agulhas had influenced the temperature, rainfall and vegetation of southern Africa —as well as the movements of its coastal inhabitants.

→‘Indeed, the Cape is a natural wonder where East meets West and the southerlies flow northwards,’ Mendle said, waving his arms out to sea. Out on the smudged horizon, amid the swirling ocean currents, lay the wind-flattened Robben Island.

→‘I know it was uninhabited, serving as a refuge for sailors,’ she said, ‘or, at least, I recall that it became a pantry, a post-box and a prison for the next five centuries.’

→He raised his leg to tighten a boot lace.

→‘Ah, Robben Island’s history as a high-security prison was inspired by the isolation of political prisoners during the Anglo-Boer War… Ironically, it’s also where Mandela spent two decades.’

→‘But Apartheid prisoners weren’t the first?’

→‘No, all manner of depraved and damned outcasts were sent to the island: runaway soldiers, convicted criminals, lunatics, lepers—even kings and princes. Mandela’s great ancestor, king Makhanda, was there. So was imam Moturu, a prince from Indonesia. The most unfortunate, however, were the sick and diseased. As you said, this was our Tiber Island. Anyway, few fuss about these miserable lepers today, having left no descendants, unlike those British convicts sent to Tasmania—’

→‘—but what about the Portuguese’, she interrupted, rubbing her slender shoulders for warmth, ‘didn’t they leave sailors on the island?’

→‘Ah, I remember something about mutineering seamen before the Dutch arrived… but my memory isn’t what it used to be.’

→He tied the other lace, pleased with his new boots.

→Her face was cold and her hands numb. She spoke quickly:

→‘They say our memory is like a dog that lies down where it pleases; yours just seems a bit restless. What more about the Portuguese?’

→The rotund scientist could sense her youthful enthusiasm. She was a colleague from the Institute for History at Leiden University and a specialist in European Expansion and Global Interaction. She’d been elected guest-curator for a forthcoming exhibition on colonial Dutch history at the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam.

→Now, here, at the Kaapse Vlek, she hoped to investigate disparities between official court records and the informal oral testimonies of the ordinary burgher. More specifically, she wanted to examine tensions between VOC officials and their dissidents, between the Companje’s rule of law and their day-to-day treatment of convicts. It would be a brief visit, so her time was limited.

→Fortunately for her, the Dutch were meticulous record-keepers and, after two long centuries, from 1602 to 1799, Cape Town’s archives provided scholars with invaluable material—including climatologists studying El Niño’s changing weather patterns.

→Mendle continued:

→‘I think it was a Dutch historian, Pieter Kolb, who noted that early Portuguese sailors were afraid of cannibals and so sought refuge on the island, around 1500, allegedly, sheltering in a cave while feasting on fried penguin eggs and roasted seal breasts. The indigenes were neither man-eaters nor war-mongerers, of course, but would retaliate savagely if provoked—’

→Mendle was cut short by the familiar ring of his mobile.

→After fumbling in his trouser pocket, he began: ‘Hello, Mendle?’

→‘Prof, Jason here, sorry to call, but last night’s storm exposed a mass grave in Woodstock’s railway yard—and it’s no traditional burial site. The skeletons are laid out on their backs, arms folded, with heavier bones than we’ve seen elsewhere. The associated material suggests they predate any foreign settlers. You’d better come look yourself…’

→Rising, his body stiff with fatigue, he sighed: ‘I say, there is always something new in this far-flung corner of Africa!’

→

→

→

Mendle’s dull blue Landi lurched to a halt on the loose gravel. He cut the rattling engine and manoeuvred himself over the passenger seat, clambering out on Sonja’s side of the cab. His door was jammed.

→The empty railway yard was located seaward of the Castle of Good Hope, along the old Esplanade, where rusting tracks traced the curve of a forgotten shoreline. Haunting street names—Beach, Tide, Spring and Marine—recalled what lay under tons of landfill.

→The midday sun now sloped across the sky as Mendle set off, Sonja by his side, between piles of sleepers and tracks choked with weeds. He led her past a disused warehouse with its derelict loading bay, and then on beyond a platform strewn with splintered packing crates and old pallets. Everything was broken, barricaded and abandoned. This corner of his paradise looked grim and grey.

→A prime location for a murder, he mused, recollecting what a once sober Inspector Morse had said: “The last to see the victim alive is usually the murderer.”

→Mendle did have a John Thaw-look about him—pale, ageing and inebriated—as if he too carried some unrequited sorrow. In her view, however, he was too talkative for a man with a silent past.

→They passed a bright red gazebo where several student-volunteers sifted through a tray of clammy artefacts. The excavators huddled together, sheltering from the fresh sea breeze, surrounded by bundles of twine, coloured pin flags, plastic buckets and trowels.

→A weather-beaten Caterpillar crawled away, like a pitbull sent to its corner, after digging under the defunct railway line. Unfettered tracks and scraps of tarmac lay scattered to one side, while red-and-white marker tape cordoned off the dig area ahead.

→A young man in khaki shorts and matching veld hat stepped up to greet them. He was lean, sunburnt, and wore mud-spattered boots without socks. He also had conspicuous tan-stripes around his thighs and ankles.

→‘Jesus, here at last! I was about to remove—’

→‘—hello Jason,’ proceeded Mendle politely. ‘Sonja, my esteemed colleague, Dr Jason Tomas, also from the SA Museum…’

→Jason shrugged, dusting off his hands.

→Was that a greeting, she wondered?

→Mendle whispered back, smiling: ‘Jason does like to talk, a lot.’

→‘Really?’

→‘Indeed, as my associate he’s never without an opinion. He’s our most talented archaeologist but, alas, also our least gifted bachelor. He loves the solitude of field-work, especially on weekends.’

→Jason drew closer, taller than Sonja estimated. Turning to her, he replied with feigned indifference: ‘As a Gemini, I’m one part alter ego and one half his Doppelgänger. Prof M explores while I discover, and that’s usually on Sundays…’

→‘Exactly, we were below Platteklip Gorge and about to unpack our breakfast when you so rudely interrupted. I should have known not to answer my phone. Anyway, show us what you’ve found?’

→‘Well then, come, follow me.’

→Jason scrambled into the dig-area, his boots sinking to his ankles at the bottom of the pit.

→‘Right here, up here above me, is where the old tracks used to be. The trench was dug to lay a storm-water pipe, but the unprotected walls collapsed overnight. There, you can see where the rain washed the loose ground away. It was the machinist who first saw the bones, and his foreman who alerted the museum this morning…’

→Sonja stepped up and peered into the gaping wound of earth.

→The pit was deeper than expected. Lying in a bed of hardened sand were several skeletons, set neatly in a row. Jason looked up, pointing his picking-tool at the rough sidewall:

→‘The trench cuts through two distinct layers. The upper section is mere landfill, dumped before the tracks were laid a century ago. The lower consists of sterile sand-deposits, suggesting the area had once been a beach or estuary.’

→Mendle knelt beside her, bending his good knee. She lent forward, like a curious spaniel, auburn hair drooping over one shoulder. Her glasses swung forward on their strap.

→‘The legendary Ma-Iti or abeLungu?’ proposed Jason wryly.

→Mendle clambered in for a closer look, his new boots sinking into a soup of sand, clay and water. She stood where it was firm and dry. Jason proceeded, waving his pick in the air:

→‘So far I’ve found a dozen skeletons lying side-by-side, orientated East-West. I’m not sure how many more there are, but then I guess we may never know. Not if Capetonians hear about another mass grave on their doorstep; even though there are no women or children this time—’

→‘—no women?’

→‘No, only men, and with variations to suggest differences in age and status. Looking at this man’s dentures, I’d say he was over fifty when he came ashore. Healthy too.’

→‘Do y’know where from?’ asked Sonja.

→‘No, not yet, as none resemble any local type. Physically, they’re all much heavier than our Khoisan. So I reckon, overseas. Perhaps.’

→Perhaps Indian or Phoenician, pondered the Professor. No, too far off to be from Malabar or Carthage. Ah, and too large to be either Chinese or Arabian?

→Turning to Jason:

→‘Perhaps they were already dead and brought ashore to be buried?’

→‘Unlikely, at sea bodies were simply dropped overboard.’

→‘Aha. Then it may have been a massacre. Even a mutiny?’

→‘Or disease,’ said Sonja, stepping back abruptly from the gaping wound, ‘but why, why would the public want to interfere?’

→‘Because scientific endeavour and popular opinion don’t mix,’ said Jason, picking grit from under his fingernail. ‘Historical evidence and public memory are like brandy and coke: never suitable in good company, yet always popular.’

→Mendle chuckled, tracing a fractured jawbone with his forefinger. He’d been through it all before, at the Waterfront, when families stepped forward claiming they’d suffered enough indignities and—with all due respect—their ancestors deserved to be left in peace.

→‘Descendants want these sites covered in fynbos and transformed into memorial gardens. That’s what they demanded last time—’

→‘—but can’t you examine the remains first?’ pressed Sonja.

→‘Who actually cares what we can prove today?’ cut in Jason. ‘With advances in bio-genetics, we’re able to determine where individuals came from, who their parents were, what kind of diet they had and even how they died. Empirically, we know more about our past than ever before—’

→‘—but it’s a loss to have them reburied,’ she said, clearly agitated, ‘future generations deserve to see this evidence.’

→Mendle made it no easier:

→‘It’s a futile debate, Sonja, a useless argument, actually, as one side favours scientific rationalisations, the other emotional justifications. Here it goes from one extreme to the other. Anyway, who are we to say what’s best for the Dead? Who speaks for their Ancestors? More so, who’ll listen to an old Italian Jew like me?’

→‘Europe has its own unwanted war memorials,’ she volunteered, ‘some citizens vandalise the monuments of their Soviet and Fascist oppressors, trashing the graves of unknown soldiers as if the dead were foreign football fans.’

→‘Sure, they may be foreigners,’ cut in Jason, ‘but not exiles, slaves or convicts. No, these were soldiers.’

→Mendle swung round: ‘Ah, why so?’

→‘Because I found metal clasps, buckles, riveted plates—and that dagger over there. Portuguese or Italian, I think.’

→He pointed to a cross-shaped object under a sheet of clear plastic. Beside it lay several lumpy, mud-encrusted items of foreign origin. They were well preserved, considering their age, having been sealed beneath a layer of undisturbed topsand and, much later, under tons of building rubble.

→Until now.

→Energy surged through Mendle’s body. He felt animated:

→‘If that’s so, Jason, then I’d say we’re looking at victims of the first pitched battle on our southern shores. See the scarred bones—here, and here, there too—these marks are made when weapons penetrate flesh and strike bone underneath.’

→Sonja felt enthralled, but Mendle had other issues to deal with now. He stood up, adding decisively:

→‘Jason, put a gypsum jacket on this one, he seems to have a ball of leather wedged in his mouth—or something equally distasteful—and bring him back to the museum. We’ll find out more about this riddle in our Lab, not here in the backyard of town. We don’t want another Sunday Times sensation. We need uninterrupted time to do this, and fast, so keep it quiet…’

→After all was said and done, the Professor returned to his dented Landi and unpacked their breakfast. Behind him scraps of torn plastic fluttered in the stiffening breeze, like the flags of a forlorn sailing ship. Beyond the barbed fence lay the Old Grey Father, Table Mountain, the ever-silent witness to many a by-gone age.

→

→

→

Mendle cut away the plaster cast with surgical precision, revealing the fragile remains of a once sturdy and mature male. He and Jason then laboured overnight preparing the skull of what appeared to be a fully articulated skeleton. They found no sign of dislocation or injury—except for several missing teeth and a severely scarred jawbone.

→Ah! Struck in the mouth from below, pondered Mendle, setting aside his titanium toolset and slumping into a chair, exhausted. He rolled his aching shoulders for relief.

→It seemed to him that a long flat blade, probably made of steel, had struck the victim under the chin. Although only further examination could confirm this. Or show otherwise.

→‘I say,’ he teased, looking up at Sonja, ‘our good Doctor may have found the honourable remains of Viceroy D’Almeida—’

→‘—unlikely,’ stepped in Jason, ‘wasn’t Almeida killed at Saldanha.’ Unprovoked, he continued dusting the delicate bones with a fine hairbrush.

→‘Not so,’ Mendle clarified, ‘as the Aguada de Saldanha changed its name to Tafel Baai only after the Dutch started calling. In fact, they took the name from the Portuguese.’

→Amused by this historical paradox, he added a footnote: ‘The use of two names caused endless confusion until each, in turn, was applied to a separate shipping station. Even today, tourists don’t realise that modern Saldanha lies 90kms north of Table Bay.’

→‘Like the anthropology student who thought Saldanha Man first appeared on Table Mountain,’ flaunted Jason, referring to António de Saldanha, the Portuguese captain who first climbed the mountain. ‘He was lost and wanted to check if his crew had rounded the Cape. From the summit they saw our extreme corner of the continent.’

→‘Some only make history when they’re lost,’ added Mendle, peeling off his latex gloves, ‘like Alexander on the endless Asian steppe, or Columbus in the unknown Atlantic.’ He opened a cabinet of surgical instruments and retrieved a half-jack and a cut-glass tumbler.

→Pouring himself a shot, he explained to Sonja:

→‘Linguists say the local Quena and Sonqua referred to this valley as the Camissa or “Place of Sweet Water”.’ He repeated the word, twice, for additional emphasis:

C a m i s s a

C a m i s s a

→‘The Portuguese,’ he noted, ‘changed Camissa to Aguada de Saldanha, thus transforming a “place of sweet water” into the “watering place of Saldanha”. This was probably done with the help of an interpreter, and may be the first act of appropriation at the Cape.’

→Men of the Word—creationists, linguists, taxonomists—men who name people, places and plants, she noted, like Linnaeus and his Hortus botanicus in Leiden.

→Mendle resumed their discussion:

→‘An early travel-writer recorded the onomatopoetic Hoerikwaggo, a Quena word meaning “Mountain of the Sea”, a word that sounded like surf rushing back-and-forth against the shore.’

→She noted it down, phonetically, questioning:

→‘Evocative, yes, but also unfamiliar, visually, at least. But why use Quena or Sonqua—is Khoisan no longer the accepted term?’

→‘Jan van Riebeeck recorded their use at the Cape in the 1650s and, today, linguists say it’s how they called themselves, so I do the same. But the matter is far from settled.’

→‘Khoisan was invented by a German anthropologist to combine two indigenous groups under a single generic term, as in post-colonial Burkina Faso,’ added Jason, ‘however, the term is inaccurate as it fails to reveal power imbalances between the Khoekhoen and San. Their relationship was similar to that between the Romans and Etruscans. The term San is itself derisive and derogatory, like Gypsy, as it comes from “forager” or “vagabond”. And yet, ironically, it appeals to the very tourists upon whom the Bushmen depend today.’

→Mendle’s mouth was dry. He paused for another sip of Glenfiddich, then beckoned mischievously:

→‘Do you realise your name has a curious phonetic quality too? Just listen to its resonance for a possible past life connection.’

→She caught the glint in his eye as he leant forward, whispering:

S o n q u a

S o n j a

→‘A mere coincidence,’ she said with interest and charm, ‘you should know I believe in chance rather than providence…’

→Despite an adolescent curiosity with past lives—typical for that age—she had no interest in it now. In fact, as a disciplined historian she avoided transpersonal theories. Even if Prof Mendle believed in that stuff, she was sure the cynical Jason never would.

→Turning heavily in his chair, Mendle proposed a break:

→‘First, something more to drink, then I’ll tell you what I know about Almeida’s murder.’

→They had locked themselves inside the Anthropology Department where Mendle and Jason shared a small laboratory. Their lab was well-equipped, spacious and secure; with its own dehumidifier, fridge and dual-function DeLonghi coffee maker. The lab was always cold in winter, too hot in summer, and drafty all year round. Up in the roof a defunct airduct released the Ancient Spirits after dark.

→It was a restless night as another cold front drove in from the sea, lashing rain against Mendle’s office windows. His door stood ajar and the hazy glow from his PC formed rotating patterns on the ceiling. Several service lights flickered down the passage, plunging elongated shadows into the inky abyss. The museum was a primordial sea of darkness where whale skeletons and fossilized dinosaurs kept watch, and mounted lion protected the effigies of the Ancestors.

→Long, long ago, long before the First Ones came, the land had been swallowed by the sea. Even the mountain was born beneath the water before it rose, giantlike, against the jealous sea-dragon. In myth, the mountain personified a titan: Umlindi Wemingizimi, Adamastor.

→‘The legendary amaRire, the First Ones, are no more real than the Atlanteans,’ warned Jason, ‘a myth is a myth is a myth.’

→He gulped down a cold coffee as Sonja reset the DeLonghi. Mendle refilled his tumbler.

→‘Ah, Cesaria Evora understood it all when she said: “Work is Work, Whisky is Whisky”.’

→‘What about Almeida?’ asked Sonja abruptly.

→What about him? Jason winced at her impatience.

→Mendle merely gestured toward a more comfortable seat.

→‘I say, let’s not presume too much. Our skull is a skull is still a skull, for now. Be that as it may,’ he added, casting a smile in her direction, ‘Francisco d’Almeida was the first Viceroy of Portuguese India and a notable ambassador, admiral and administrator. Bartolomeu Dias, Vasco da Gama and António de Saldanha were among the few to round this sea-girt Cape before him. Following historical sources, Almeida and fifty-seven men, perhaps more, were killed when they came ashore, some say on the old beach below District Six. Sadly, the shore disappeared when a deeper harbour was built, around the time steam-ships began calling at the Cape.’

→He sipped his drink as Jason continued their preparations, brushing out debris from between the bones.

→‘To make a long story short, a group of sailors and soldiers—no doubt unsavoury, sunburnt and unshaven—found some herders from whom they tried to obtain, or more probably, from whom they tried to steal a few head of cattle. However, the latter didn’t want to barter as a fattened herd symbolised status, wealth and prosperity. In return, the seafarers gave away mere trinkets—felt caps, pewter rings and glass trade beads—unwilling to exchange their own swords, lances or crossbows. Obviously.’

→Jason smirked: ‘So, instead, our Khoisan pilfered a few knifes?’

→‘Exactly, until someone hurled abuse and they began to brawl. The outnumbered sea rogues—twelve in all, I think—fled to the beach where a longboat awaited them. One of these was Almeida’s servant, who returned with a bloodied nose and his teeth broken.’

→Mendle paused, inserting his own nose into a swirling tumbler.

→‘Once aboard the flagship, the humiliated men asked Almeida to go punish the villagers. Reluctantly, he agreed, and so early the next morning, probably before sunrise, he led an ad hoc party ashore. Several men ran ahead to raid the village where—as far as I know—the first white man was killed on our southern shore. An accident, they say, as he was stabbed by his over-zealous compatriots in the chaos. The other men returned with what cows they could steal—and some children they had kidnapped.’

→‘Children?’

→‘That is, men of small stature. It was common practice to educate abductees back in Lisbon and then, years later, to return with them as linguas or interpreters. However, after that, their lives were full of contradiction and confusion, as neither Whites nor Blacks would treat a lingua as their own.’

→Mendle fell silent, momentarily distracted by his own experience as a marginalized academic: Again and again, the eternal outsider.

→‘Shall I go on?’

→‘Please do, Prof, while I wait for the pot.’

→She held up a packet of Ethiopian highland coffee, a birthday gift, from friends in the Museum Café downstairs.

→‘No-well-fine,’ he said, lifting his tumbler. ‘Now, where was I?’

→‘The punitive party was ambushed,’ said Jason, as the aroma of percolating coffee filled the Lab.

→‘Ah, yes, Almeida and his men made a forced retreat to the beach. Unable to flee, they fell back between the dunes and rising tide until about sixty more were dead—all victims of fire-hardened spears and slingshot-stones. According to eyewitnesses, Almeida died kneeling in the sand, his eyes lifted up to heaven, with an assegai through his throat. Jorge de Mello Pereira, a trusted officer, managed to flee and returned that same afternoon to bury the dead.’

→Mendle wiped his lips, concluding gravely:

→‘I could lose my job if the authorities find out what I’ve got here. Concealing these bones is not only illegal, but also unethical, so I’d prefer to keep our work a secret, please.’

→She knew that the illicit trade, collecting and exhibition of human remains was a sticky business—even diplomatically. The bottled head of Badu Bonsu, an Ashanti king from the 1830s, was a grim example. Like the Tropenmuseum, Leiden University had been returning its specimens for years.

→It was the Barcelona Olympics that shook the museum world when black athletes threatened to boycott the games if a stuffed El Negro remained on view in a local museum. The “Bechuana Bushman” was most probably a moTswana whose body had been stolen after burial, also in the 1830s, and then taken to the Cape Colony where it was prepared for exhibition.

→Right now, she reflected, their El Portu could jeopardise renewed restitution projects in South Africa.

→‘Your secret is safe, Prof,’ she added cheerfully, turning to Jason.

→‘Jesus, it’s not like I’m going to tell anyone! That’d be professional suicide…’

→Jason packed away his tools, ever so methodically, then flashed a rare smile: ‘Alright then, no problem.’

→Mendle was visibly relieved:

→‘By the way, there’s only one historical depiction of the massacre, published two centuries later, by a certain Van der Aa,’ raising an eyebrow, Mendle winked, ‘and he’s also from Leiden.’

→Sonja had to laugh, saying: ‘Well, I’d rather not assume any karmic connection.’

→Mendle beamed back.

→She knew the artist’s œuvre and filled in: ‘Pieter van der Aa was an entrepreneur who, rather rapidly, became the city’s top printer, the university’s leading publisher and the country’s least liked bookseller. He had a shop on the Rapenburg—our most beautiful canal—and his travel books were renowned for their illustrations; especially those with random scenes of Africa.’

→Jason was speechless: Does she ever breathe?

→Mendle left to fetch a book from his adjoining office. Returning, he stopped to show Sonja a fanciful depiction of huts, palm trees and fighting men on an otherwise deserted beach—all viewed from the safety of the roadstead. The ships were not Portuguese caravels but Dutch galleons, she noted, which revealed more about the engraver than it did of the event itself.

→‘Ah, then this Van der Aa was not the actual artist?’

→‘No, nor was he an explorer or traveller. I think the farthest he ever went was to the Frankfurt Book Fair.’

→Still beaming, Mendle proposed: ‘As far as I know, the national military museum has the only other depiction of the event—a modest painting by a local artist, a woman, or so I recall. Say, why not visit the Castle tomorrow while I catch up on some lost sleep?’

→

→

→

The Castle of Good Hope was the oldest extant building in South Africa, a cornerstone of colonial history, and still in mint condition. Built on the beach in 1666 to defend VOC possessions, it had never been besieged—except by busloads of trigger-happy tourists.

→Jason was there, as agreed, ensconced on the terrace with an empty espresso. His casual demeanour made even the cane-furniture look comfortable. With his leather satchel slung over a chair and an open notepad lying on the table, it seemed he’d been there all morning. She drew a chair while, with a confident flick of his fingers, he hailed the slim cinnamon-coloured waiter at the bar.

→Sonja had been out for a brisk walk and, dressed against the cold, now wore a knee-length coat and knitted scarf with her favourite tortoise-shell glasses. The latter were fashionable any time of day—particularly after a late night in the Lab.

→‘It seems odd that one hundred and fifty soldiers,’ he said, once she’d settled, ‘of whom most were well-equipped and experienced, could be so easily overwhelmed by a group of angry pastoralists.’

→‘So then, how many lived in an average Quena village?’

→‘About two hundred, maybe three, including women, children and the elderly.’

→‘And fighting men?’

→‘One hundred, perhaps more, but their throwing sticks were useless against the crossbow, lance or sword. Headless spears were no match for weapons of steel.’

→‘So what chance did the Quena have?’ She removed her glasses to see him better.

→‘Chance, against these odds? Only one. Oxen. They had a herd of trained war-oxen which, when driven together, formed a formidable battering ram or protective shield. Early writers observed how they leapt like agile dancers between their stampeding cattle.’

→She listened as his hands mimicked the movements of men and beast, his expressive gestures revealing more than his face allowed… He was handsome, yes, but too nonchalant for her.

→‘So what’s your point, Jason?’

→‘Almeida wasn’t crushed in a stampede.’

→‘What?’

→‘The skeleton we found is undamaged. Almeida—or whoever the skull belongs to—was slain in close combat by a hand-held weapon. The point of entry was under his chin and made by a controlled thrust. The blade smashed out his teeth and was sufficiently flat to leave parallel scars along his jawbone.’

→‘Then wooden sticks didn’t kill him?’

→‘Who knows, he may have had other injuries and bled to death, even drowned. Whatever, only his bones can tell us now…’

→Jason rose to settle the bill. She watched him saunter over to the waiter, a rakish Indonesian boy, with whom he chatted while paying. He returned smiling. Rare indeed.

→He led her across the manicured lawn, neat as a billiard table, until they reached the entrance to the Castle Military Museum. Here a security attendant directed them toward the painting.

→It was a vivid and dramatic work. Hemmed in between the rising tide and falling dunes, the Portuguese defended themselves against the fearless herders and their frightened oxen. Two figures dominated the foreground: one with a raised assegai, the other drawing his sword.

→Almeida, certainly. His face was obscured, as if the painter wanted to avoid a portrait. Perhaps no reliable likeness existed?

→According to the accompanying text, the artist had been inspired by a local illustrator, one Angus McBride.

→While most seventeenth-century artists never saw the Cape—a fact Jason was pleased to point out—this one probably stood on the beach himself. Or rather, herself, if Mendle’s memory was to serve them well. Either way, the details were too specific for an outsider.

→Jason came and stood behind her. She lent in to read the text:

→‘It says the herders whistled and shouted, driving cattle against the heels of their foes. The sixteenth-century chronicler, João de Barros, writes that Almeida’s men were surrounded and fell in the soft sand, wounded and trampled, as few wore armour and for weapons had only lances and swords.’

→She looked over her shoulder as he turned away, his voice derisive:

→‘Whatever, soaked in history, the chroniclers fail to convince me. Their facts don’t add up…’

→‘Perhaps,’ she suggested, ‘perhaps our best clues are in the Lab?’

→‘Too late. Prof M asked me to re-seal the remains until the threat of confiscation passes.’

→She looked puzzled.

→‘I agreed to do it on Saturday.’

→‘Then you really are his alter ego.’

→‘Only on weekends,’ he said with a wan smile.

→‘So you do smile, after all?’

→He avoided the implication, noticing how white her teeth were, and proposed they visit the military library upstairs.

→He led her out, via Reception, and up the narrow stairs.

→‘I-i-if it wasn’t an accident,’ she stuttered, reaching the last step, ‘if Almeida wasn’t killed by oxen or fire-hardened spears, then he must have been murdered by his own men?’

→It seemed to her that there was no marginal space where Africa’s past and Europe’s history did not intersect; no beach below Table Mountain where the footprints of both native and interloper hadn’t overlapped. Furthermore, she realised, there was no reconstruction of Almeida’s murder from which either party could now escape.

→

→

→

Francisco d’Almeida was born around 1450, in Lisbon, and served the court as a diplomat,’ began Jason, as Sonja browsed between the over-laden bookcases, careful not to trip.

→Excess books had been boxed, bundled and stacked along the aisles. It felt like a cold storage room, not a book repository. The Castle had been built against rough seas, not rising damp. A shivering archivist sat in the corner, alone, guarding his oil-heater. From what she could see, they were the only visitors in the library.

→Checking the wall clock (they had less than an hour before closing), she handed Jason a monograph: ‘Here, start with this…’

→He went and sat at the reading table, his fingers skipping through the pages, plucking information at random. Reading aloud:

→‘According to the seventeenth-century royal historian, Manuel de Faria e Sousa, Almeida was the son of Lopo, first Count of Abrantes, and a knight in the Portuguese Order of Santiago… Almeida was graceful in person, ripe in council, continent in action and an enemy to avarice. He was liberal and grateful in service and obliging in carriage. In ordinary dress he wore a black coat… though later it was a sleeveless cloak or doublet of crimson satin, with black breeches reaching from his waist to his feet.’

→‘Like the one we saw downstairs?’

→‘Possibly.’ Jason skipped on: ‘Almeida acted as an ambassador for the ageing king of Portugal, Afonso V, trying to unite him with the young Juãna la Beltraneja, a child-princess from Castile… He visited France to secure support for this alliance—’

→‘—but Afonso didn’t succeed,’ said Sonja, coming to stand by the table, ‘the French favoured an alliance with Castile for themselves.’

→‘Thus the French supported Castile, not the Portuguese?’

→‘Yes, making it a financial setback for Afonso who needed France’s backing for his North African crusades… He was called Afonso “the African” because of his success against the Moors, most of whom were Muslim Berbers, Islamized Slavs or Moroccan slaves. And he used the Reconquista to unite Portugal and Aragon.’

→‘Then it was Portugal and Aragon versus France and Castile… like a quarter-final in the UEFA Champions League?’

→Sonja smiled, recalling what else she knew of Europe’s expansion: ‘Diplomatic relations floundered while neighbour states bickered over the spoils of war—especially all that gold from Africa.’

→After an inevitable sea battle, Portugal and Castile split the world between them, pole to pole, East from West, with Portugal securing sovereignty over all African trade. The line was redrawn by Spanish-born Pope Alexander VI, Rodrigo Borgia, that “rapacious wolf”, midway between the discoveries of Columbus and Portugal’s existing possessions. Rome always devoured its prey like a wolf, but now it faced a New Troy—Lisbon had come of age.

→Fatigued, Sonja eased in beside Jason, reading over his shoulder:

→‘It says Almeida was dismayed by all the bidding for Juãna’s hand. Not because she was illegitimate, or still so young, but because he no longer felt national destinies should depend on arranged marriages. It appears he thought royal alliances were archaic and that Europe’s future should be better served by its elite mercantile class.’

→‘Whatever he felt for national destiny or historical will, he was also engaged by Isabella and Ferdinand. He was their confidant too.’

→‘Right, the Catholic monarchs united Castile and Aragon to form a single Spanish state in 1492, finally, after the expulsion of the Moors. In short, Almeida served the kings of both Spain and Portugal, each with their own allegiance to Rome.’

→‘How d’you remember all this detail?’ He looked at her askance, sitting too close to meet her gaze head on.

→‘Easy, I memorise the decade and year, the century is obvious.’

→‘Well, it clearly works for you,’ he said, noting the time difference between European history and African archaeology. The clock ticked on as he ran his finger down the next page, reading rapidly:

→‘Francisco d’Almeida was an inspired strategist who took command of the sea and secured the oceanic trade route to the Indies… but was reluctant to spend limited resources on costly territorial footholds, unlike his successor, Afonso de Albuquerque—’

→‘—that’s unusual,’ she interrupted, ‘as Europe’s overseas expansion depended on the capture and possession of new lands.’

→‘Like the English, who rushed ashore on seeing a Dutch fleet enter Table Bay, shouting “For King James!” They claimed the Cape and all the land between it and their nearest Christian neighbour, Prester John, then several thousand miles away. That’s in 1620.’

→Laughing again: ‘I see you do recall dates too.’

→‘Sure, I do dates, while you can be so brutally honest!’

→‘No, the Portuguese were brutal. Tristão da Cunha cut off women’s hands to steal their bracelets…’

→His smile faded, looking away: ‘Colonialists always impose a culture of violence on those they conquer, convert or civilize—’

→‘—perhaps, but what about cultural or commercial exchange?’

→She began paging through her own book.

→‘Same-same, but look here!’ he said, prodding her with his pencil. ‘Almeida commanded the most decisive naval battle in the history of the Indian Ocean, in 1509, when his fleet destroyed the Egyptian, Arabian and Persian navies at anchor off Diu in north-west India… This victory not only ensured Portugal’s monopoly of the sea, but set the political stage for another five centuries…’

→Jason became animated. She put a cautionary forefinger to her lips, adding quietly: ‘The ocean was a vast neutral zone. At that time no one dared deny others the right to sail the seas.’

→He shrugged, half-listening, half-reading: ‘Sure. It seems more men died at the Cape than all those at the battle of Diu.’

→‘Diu repelled Islam from the East and not, as had been tried before, by advancing overland from the West—’

→‘—right, it was a culmination of eight centuries of conflict between Mediterranean Muslims and European Christians, an animosity that began with the invasion of Iberia in the eighth century. The first to set foot on Gibraltar,’ he added, ‘was the formidable free-slave from Morocco, General Gibril Tarik.’

→‘Hence the name Gibral-tar,’ she acknowledged.

→‘Right. My favourite uncle told me how Tarik made his men burn their boats: “My beloved brothers, we have the enemy in front and the sea behind us. Now we can’t go home. We shall either defeat the enemy or die like cowards by drowning. Who will follow me?” I loved that story, even if Uncle Noor made it up!’

→‘Wait, back to the battle of Diu, I see it was more than a military victory, it was an act of revenge. His son had been slaughtered—’

→‘—Almeida, a father?’

→‘Yes, which means there was a woman too—here, read it. Married or not, Almeida was probably in love at least once.’

→It was her first insight into Almeida’s private life—like looking at an unfamiliar Dutchman and knowing he had, if only once as a child, sat on the knee of Sinterklaas. Catholic or not.

→With cold impartiality, the archivist announced the library would be closing in ten minutes. Jason hurriedly picked for more:

→‘Lourenço, an only son… killed a year earlier… in 1508. Husayn al-Kurdî, commander of the Mamluk fleet from Egypt, ambushed him at Chaul harbour… The Portuguese had the upper hand until, for a shrewd price it seems, support came from the naval chief and master of Diu, Malik Áyáz, a former Russian slave… In the end, a combination of extra ships, swelling tide and bad timing cost Lourenço an arm and a leg. Literally,’ he grinned, ‘as both his limbs were blown off by two successive cannon balls. The ship sank with him tied to the mast, leaving only a handful of survivors—’

→Appalled by his humour, she cut him short:

→‘—and the rest of Lourenço’s fleet?’

→‘They escaped. It was a devastating blow for Almeida who, finally, stepped down as Viceroy, but only after avenging his son’s death…’

→Despite all she recalled of European expansion around 1500, she knew little of Africa or India during the next century. Her area of specialization was Dutch seventeenth-century mercantile exchange with Indonesia and Japan—Holland’s so-called Golden Age. Now, at this cornerstone of South African history, her own histoire was about to change.

It began as an accident—like most scientific discoveries or inventions. Her feet felt clumsy, even stupid. Turning to leave before the library closed, her one shoe hooked the corner of a box and several books scattered to the floor. Embarrassed, she bent to retrieve them before the archivist could intervene.

→Gathering the last items into her arms, a scuffed dossier fell open to reveal its contents: pictures, maps, notes, photocopied articles and some handwritten lists. Then, on a library requisition form, partially obscured, her eye caught sight of six blurred letters in faded ink:

A L M Y D A

→She checked again… had she begun to see his name everywhere, like the face of a beloved lost in a crowd? Dalmeyda definitely, yes, and among his portraits a scrawled note that warned:

Whosoever believes in the eternal recurrence will die the same death, over and over, until the last is silenced forever.

Sonja heard a heavy chair draw back, followed by approaching steps. There was no time to read more. Instinctively, she slipped the dossier from sight, under her coat front, as the Shivering Archivist came up to collect the books.

→Flushing, she apologized, offering what books she held in her free arm. He brushed against her breast, accidentally, fumbling the pile with a frayed woollen glove:

→‘The box was left on our doorstep, unlabelled and unidentified, as if someone wanted it out of harm’s way—like those Russian posters left on the front steps of the SA Library in 1960, the night before the ANC and Communist Party were banned. The stuff in our box is still unclassified. An expert was meant to sort it out months ago, which is why the box remains in the aisle. Here, let me clear it out the way.’

→He shoved the box aside and returned to his desk, locking his top drawer and unplugging the heater. She heard him pocket his keys.

→‘Thank you,’ she said, not sure of her next move, ‘we’ll be done in a minute.’

→Check the dossier.

→She turned away from the archivist, keeping the dossier flat against her tummy. Jason came round and stood behind her.

→‘What’s this?’ he hissed, aghast.

→‘Wait. Watch my back.’

→‘Whatever, he’s busy. You’re safe.’

→She leant against Jason’s shoulder, easing free the dossier, while the chilly bibliophile secured his filing cabinet for the night.

→She peeped inside again.

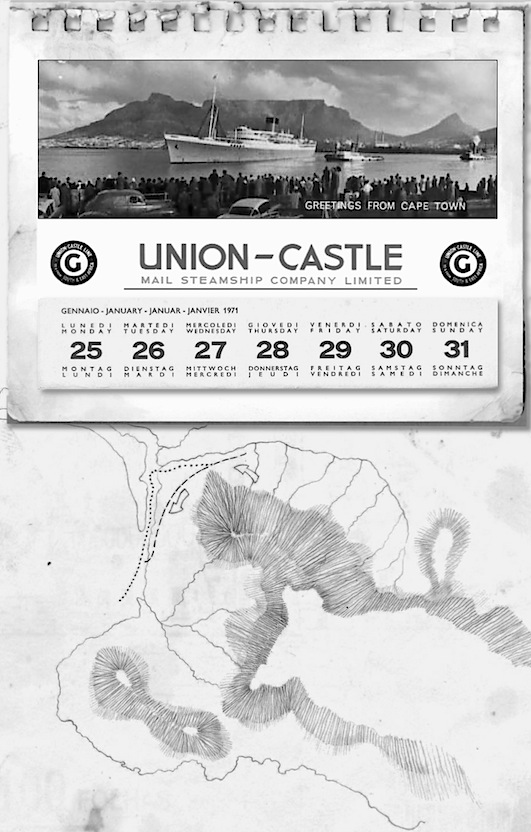

→There were pencilled comments in the margins, sepia photographs, souvenir postcards, an old Union-Castle Line calendar, a wire-ring notepad and some biographical tables, entitled Tabula nomens. Three embossed letters, WJS, appeared on the outside flap, presumably to identify a past owner. Sonja lent in, holding onto Jason as she read:

On leaving Cochin the sorcerers, or astrologers, warned that Almeida would not pass beyond the Cape of Good Hope… it being the portal to the Estado da Índia and the border of his realm. Passing it in fine weather, he said to his attendants: “Now, may God be praised, the witches of Cochin are liars.” A few leagues farther, after coming ashore, he was slain and buried at the watering place of Saldanha.

No matter how irrational it seemed—or however criminal it would appear to others later—Sonja knew she was going to steal the dossier. There and then.

→The idea was as unexpected as it was reckless. She’d never done anything like it, not even a lipstick from the Bijenkorf. But this was neither the time nor the place to justify herself. She would tuck it under her coat, again, and simply walk out.

→But wait, first another peep, a quick squizz at the prediction cited below. A curse, it seemed, by the same Manuel de Faria e Sousa:

→‘Hey,’ she whispered over her shoulder, ‘it says divine judgements are unfathomable… the superstitious talk of ill fortune and bad luck when Providence is really the only explanation. O Providéncia, I think Prof Mendle would like this!’

→

→

→

Professor Mendle lived in a Victorian semi against the rim of the city bowl. It was a balconied double-storey with a secluded garden that slumbered in the mountain’s shadow—like Mendle himself.

→He had bought the house in the Seventies when everyone else was peeling enamel paint from their panelled-doors, sash-windows and trellised verandas. When back-to-nature was fashionable and truth-to-materials represented honesty and integrity—yet manual labour did nothing for the vanities of a serious academic.

→Sonja and Jason now stood in front of the only house with gloss-white fixtures. Symphonic music muscled its way under the door and through the wrought-iron gate. A Wagnerian opera. Morse.

→‘Try again.’

→Jason hammered at the door until a dishevelled Mendle let them in. Wrapped in a blanket, pharaoh-like, he led them to a darkened study where half-drawn drapes hid a pair of jammed sash-windows.

→It was a cramped but comfortable mess.

→A teetering bookcase held up the sagging ceiling while bundled journals stood like sentries at their posts. Mendle’s desk was strewn with newspapers, crossword puzzles and a framed photo of his late wife. Her favourite cat slept on his flattened leather briefcase.

→Mendle offered no excuses for his appearance, except to say that had Jason and Sonja not called, he may have looked more refreshed after a longer nap. There was no food in the house, either, not even a frozen meal, so perhaps they’d better go get something to eat?

→‘We came to show you this dossier—here, take a look—and to ask about the uncanny prediction concerning Almeida’s death?’

→They pointed to the reverse side of the UCL shipping calendar.

→‘Ah, I see you found the witches’ prophecy,’ he said cautiously, ‘but we don’t really know if it’s fact or fiction. The Lusíads only appeared after the massacre. In fact, all in all, sixty years after.’

→‘Is that how long it takes to write an epic?’ taunted Jason, recognising the title.

→Mendle chuckled. ‘Luís de Camões worked on it for over a decade and saw it published, finally, in 1572. It’s the inspired history of a restless Portuguese nation who, as someone once said, were a “small people of big deeds”. However, it’s no history, but an allegory focusing on Vasco da Gama’s historic crossing to India. Os Lusíadas simply means the “Sons of Lusus” and describes the adventures and fortunes of all who doubled the Cape… including the prophecy that Almeida would not pass this threshold on his return from India. But having safely done so, Almeida believed his curse was lifted or, at least, that it would not be fulfilled at the world’s southernmost Portal.’

→‘So, what happened?’

→‘Ah, but he didn’t pass beyond the Cape, did he? While we still don’t know whose skull it is,’ said Mendle, lowering his voice, ‘we do know that Almeida was struck by his own men.’

→‘Jesus, not with that dagger we found next to the skeletons?’

→‘No, with a long flat blade,’ he replied, before Sonja could ask:

→‘I thought he was ambushed when his punitive expedition failed?’

→‘Well, that’s still true, but it didn’t end like that,’ whispered Mendle. ‘I asked a friend for his advice, a psychiatrist who also happens to be clairaudient—a healer empowered by the Ancestors—like a shaman or sangoma, but one who doesn’t trance and hallucinate. He’s usually awake or conscious when the ancestral spirits speak to him, and hears the story behind a person’s life, or the story behind a ring, a watch, a handkerchief and even, say, the story behind a photograph—’

→‘—or behind a rusty old dagger?’

→‘Aha, yes, even that rapier you found. I showed it to him yesterday, only to look at, of course. He doesn’t only hear things, but voices also tell him about individuals and their past lives. He sent an email, just half-an-hour ago, to say that Almeida’s murder was not an accident. It was premeditated. What happened remains true, yes, but not in the way historians have chosen to record it.’

→‘—and the dagger?’

→‘I have it back again…’

→‘I mean, was it used?’

→‘Ah, no, the rapier didn’t kill him, it was used to defend Almeida. It seems to have belonged to one Gaspar das Índias, a skilled linguist, who first served Gama and, a decade later, died defending Almeida. Look at the message, here, I printed it for you.’

→He handed them a page with two typed paragraphs:

Gaspar of India was a close confidant of Francisco d’Almeida and privy to his esoteric concerns. Almeida was well aware of those factions within the Catholic cabals that were antagonistic toward his secret commission to reopen channels of esoteric intercourse between East and West, and that they sought to destroy not only his work but also his life. They had already succeeded in having him displaced from his position as Viceroy of the Indies, and so on his final return to Portugal, unsure of anyone else in whom to trust, he confided in Gaspar that he was in peril of his life.

It was thus at the Cape of Good Hope that the conspirators struck and carried out an order of execution, disguised as a prophecy of doom, that Almeida should not pass beyond the Cape. The ambush was carefully orchestrated as an altercation between the sailors and the irate natives. Gaspar, the one officer who shared Almeida’s anticipation of assassination, died defending his captain. The Viceroy was already dead, and his party wiped out, when the conspirators returned to seal their atrocity—ritually piercing Almeida through the throat with a lance of steel. Thus they silenced him forever.

It took Sonja a moment to process the revelation:

→‘So Almeida was assassinated?’

→‘More than that, he anticipated it—’

→‘—but how did he know about the prophecy,’ she hastened, ‘if it was only written sixty years later?’

→‘Aha, that’s a good question. I always thought Camões invented the witches’ prediction for dramatic effect. Now, indeed, it appears to have originated before Almeida left Cochin.’

→‘W-wh-which,’ she stumbled, ‘w-which is why Almeida rewrote his last will and testament before reaching the Cape?’

→‘Yes, like Camões, he believed in oracles and soothsayers.’ Mendle pulled his beard, musing aloud: ‘Both men were superstitious enough to take omens seriously and, as enlightened Christians, still believed in pagan prophecies. Let’s just say they both sensed things weren’t as simple as they seemed—’

→Jason butted in: ‘—for which the restless Native had to be blamed?’

→‘Aha, the assassins had to cover their tracks, and so their crime was executed far from home and without witnesses. Yes, rather cruelly, it was the perfect execution.’

→‘But why,’ she said bewildered, ‘why, when he was an esteemed administrator and an acclaimed admiral?’

→‘Perhaps,’ said Mendle, enrolling himself as her mentor, ‘perhaps some thought him disloyal?’

→She checked: ‘How… y’mean disloyal to the Crown?’

→‘Yes, he could have betrayed a state secret or misused the spoils of war, and so deserved his punishment. I recall something about this in an essay I was given by a priest, which should be around somewhere. I’ll have to look for it later. Anyway, the Portuguese nobility belonged to one of three militant-religious orders and competed for resources. Almeida himself belonged to the same Order that had once financed Prince Henry’s endeavours. These knights also revived the Templar code and enjoyed spiritual and material privileges, but were severely punished for acts of disloyalty—paying the ultimate price for treason or mutiny. Say, Sonja, now show me the dossier…’

Fin