So, why is South Africa House in London and not Lisbon?

This page serves to share my ideas with those who couldn’t join us in London to celebrate the launch of Knot of Stone. We were delighted to see so many friends—young, old and new—from Cape Town, Pretoria, Lisbon, Amsterdam and, of course, London (see below for social pics).

Yes, so why is it in London and not in Lisbon? Actually, let’s turn that around and ask why South Africans flock to London and not to Lisbon? Is it because they prefer the cold, grim and grey English weather to Portugal’s azure coast and sunny resorts? Odd indeed, isn’t it, after Cape Town was itself billed a cultural resort only a century ago.

Is it because South Africans prefer cricket and rugby to bullfighting and horse rodeos? Or is it for the royal family, the pound and the best pint of bitter one can buy abroad? Well, first and foremost, it’s because South Africans speak English and not Portuguese. They also sing the same language, the same songs, and the same Christmas carols.

Is it because South Africans prefer cricket and rugby to bullfighting and horse rodeos? Or is it for the royal family, the pound and the best pint of bitter one can buy abroad? Well, first and foremost, it’s because South Africans speak English and not Portuguese. They also sing the same language, the same songs, and the same Christmas carols.

Perhaps it’s also for the Bentley, the Aston Martin and the Land Rover? Or, more practically, just because the English drive on the same side of the road. In fact, the Brits gave them a traffic ordinance, a legal system and their first governmental institutions. They also gave them their first Parliament, Supreme Court, City Hall, University, Botanical Garden and, before the boycott, their first vegetarian restaurant. Moreover, they introduced traditional English flower shows, rose gardens, horse racing and trout fishing.

The Portuguese, on the other hand, introduced the first post office and prayer chapel in South Africa. Or rather, the Portugales left behind a sailor’s boot hanging in a tree and some calico sheets flapping in a bush. The boot-tree became the country’s first post office, the bush-shelter its first place of Christian prayer.

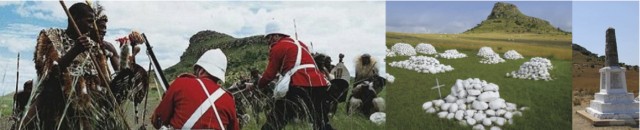

And, of course, South Africans favour the Brits for the battlefields and war memorials they left behind. Unlike the Portuguese, who merely left a wooden cross and a pile of stones at the Cape. As the Bard says, nothing will come of nothing.

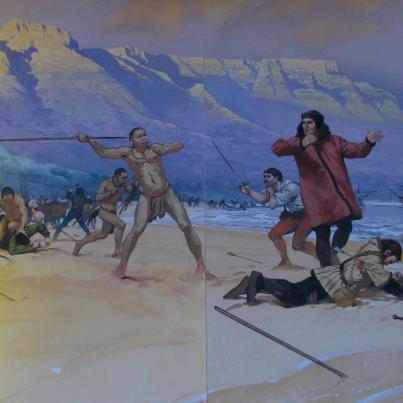

In fact, this cross and cairn not only marks the first battle scene and earliest known war memorial in South Africa, but also marks the site where Francisco d’Almeida, the disgraced Viceroy of Portuguese India, was brutally killed. Unfortunately, both cross and cairn have long since disappeared.

As most of you know, my book begins with the chance discovery of several skeletons on an old beach below Table Mountain. For those who haven’t heard, Knot of Stone is a tale of historical detection in which a Dutch historian and an Afrikaans archaeologist try to reconstruct what happened five centuries ago. They find themselves on the trail of a lost Aristotelian manuscript, crisscrossing Europe in a vintage coupé and chasing down every possible clue, while being pursued by a zealous mercenary themselves.

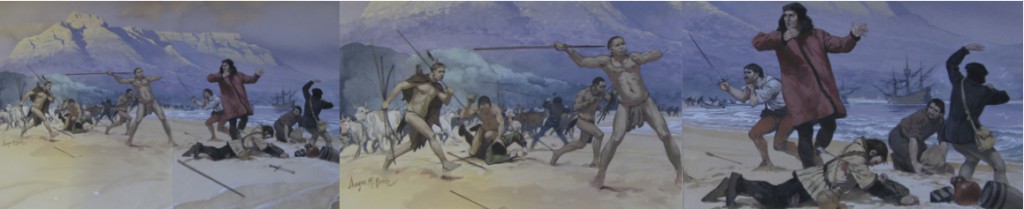

The murder of Viceroy D’Almeida occurred when a Portuguese party came ashore at the Cape of Good Hope in 1510. Within hours Almeida and sixty compatriots lay dead and buried in a shallow grave. His murder remains a mystery to this day. Was it the fulfillment of a prophecy or an act of poetic justice? Was it an ambush, a mutiny or even an assassination? If so, was it instigated by the King of Portugal or the Church of Rome?

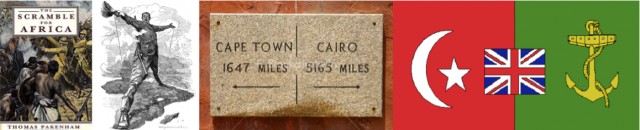

Though seldom mentioned by historians, this isolated massacre changed the course of history—first in southern Africa, then across western Europe. According to contemporary records the Portuguese king, Manuel I, saw Almeida’s death as a great loss and forbade his captains from calling at the Cape—unless in dire necessity. The Portuguese thus abandoned the Cape of Good Hope and seized Angola and Mozambique instead, thereby leaving a most strategic southern coastline for the Dutch and English to occupy.

This not only set South Africa on a different trajectory, politically, but sealed its cultural and religious fate. The country would emerge as a partner of Western Europe—and not the Mediterranean south—wherein Protestants and Anglicans were favoured over the Catholics. Over the centuries the Cape submitted to the pragmatism, rationalism and jurisprudence of the North: to Roman Dutch Law, the German Reformation, the French Huguenots (themselves anti-Catholic) and, much later, to the grand mining magnates of British Industrialism. The Inquisition would pass them by, but not a prejudice towards Blacks and Jews.

The subsequent discovery of diamonds and gold in South Africa not only consolidated Britain’s colonial possessions, but also helped bolster its assets at home. The English were here on a good wicket—they’d not only succeeded the Portuguese in India but were the main successors of the Dutch in Africa.

The Portuguese, of course, wanted to prolong their innings at all costs. In fact, they wanted to bat and bowl at the same time. They wanted Mozambique for its proximity to India and Angola for its cultural ties with Brazil. Although Mozambique had less friendly neighbours, the legendary gold of Monomotapa hadn’t proven to be as lucrative as that of Elmina on Ghana’s coast. On the other hand, Angola was rich in oil, iron and diamonds and had exploitable territories like Cabinda.

But back to the initial question about London. Well, given the scenario I’ve sketched out here, it’s not surprising to see so many South African landmarks in and around London.

South African war memorials litter the British Isles, as do statues of former statesmen like General JC Smuts. Today the most famous, certainly the most popular, is the bronze sculpture of Nelson Mandela on London’s Parliament Square.

Even as a novel, Knot of Stone looks at what actually happened rather than what may have been. While it points out where historical trajectories altered course—from the succession of Alexander’s empire to Monty’s successes and the outcome of World War II—Knot of Stone traces the lives of men like Julius Caesar, Constantine the Great, Charlemagne, Winston Churchill and Dag Hammarskjöld.

The death of Hammarskjöld, like that of Almeida’s, offers more questions than it does answers. Read the article Exploring past and future lives—Dag Hammarskjöld.

Nicolaas Vergunst

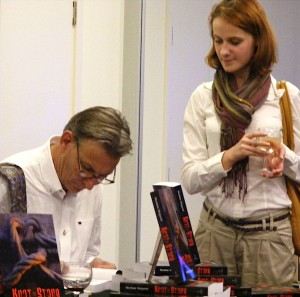

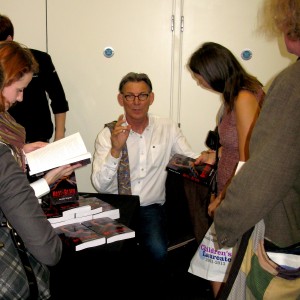

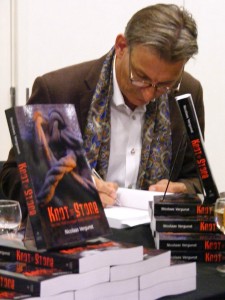

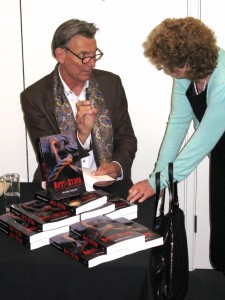

Knot of Stone book launch, Europe House, London, 5 September 2011

Publisher James Farrell introducing the author at Europe House, London, 5 September 2011.

Publisher James Farrell introducing the author at Europe House, London, 5 September 2011.

Monday 5 September 2011—Knot of Stone is launched in Europe House, London. James Farrell of Arena Books kicks off with the these words:

We at Arena Books are very proud of having had the opportunity to publish Knot of Stone, which we feel is a remarkable novel in a category of its own. I say this because, like Melville’s Moby Dick, it is a novel which can be interpreted on several different levels. It is clearly a story on an epic scale, and as the author remarks in his Preface, the book “straddles different genres.” It is primarily a work of historical fiction, but in its search for facts or greater clarification of a very murky episode early in South Africa’s history, it seeks to reveal a number of underlying truths of existence which touch us all.

In explaining his approach to what we know of the historical facts, the author writes: “I chose the novel form over that of the travel journal, biography or monograph because it is better suited to ‘that willing suspension of disbelief.’ I hope readers will also suspend their belief when it comes to matters of faith and doctrine, just as I tried to avoid being dogmatic or coercive. My story is based on what I imagined, and now believe, happened that ill-fated Friday morning below Table Mountain; Almeida was ambushed and killed, then ceremonially executed in a bizarre retribution—a death both real and symbolic.”

In another passage, the author further elaborates on the inter-connection of events in time and space, when he says: “I uncovered mysteries riddled with secret symbols and sacred codes; adventures loaded with teenage magic and medieval legend; as well as thrillers bristling with immortal warriors and incarnate warlords… Then too, I also espied romances flirting with reincarnation.”

The book is beautifully and simply written. Its gripping narrative transports the reader unexpectedly into surprising realms of new experience and, to our joy, into ingenious lines of enquiry. In addition to this are the wealth of illustrations accompanying the book; from the fascinating chapter heading motifs which stir the imagination and arouse curiosity, to the many historical, religious, scientific and mystical pictures which help to make this a book a treasure for its readers for many a year ahead.

A work of fiction it may be, but it is moreover a work of education in the breadth of its exploratory range. It would need to be a person of very dull temperament who does not find this novel an enthralling read to which he may return again and again for a special kind of enlightenment. I recommend Knot of Stone as a must for all booksellers and librarians to stock.

James Farrell

To celebrate the launch of Knot of Stone in London, the Netherlands’ Ambassador HE Pim Waldeck hosted a luncheon for distinguished guests at the Dutch Residence in Exhibition Road.

From left to right: the auth or, Nicolaas Vergunst; HE the South African High Commissioner, Dr. Zola Skweyiya; and HE the Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Mr Pim Waldeck. Standing behind them is Mr James Farrell, Director, Arena Books, publisher of Knot of Stone. Those present but not on the photo include: HE Mr João de Vallera, Ambassador of Portugal; Professor Jack Lohman, Director of the Museum of London; Emeritus Professor Malyn Newitt, Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at King’s College London; Mr Steven O’Brien, Editor of The London Magazine: a Review of Literature and the Arts; Mrs Ellen Berends, wife of the author; Mr Jan van Weijen, Cultural Counsellor of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and his colleague Mrs Ciska Dijk, Attache Education and Literature.

or, Nicolaas Vergunst; HE the South African High Commissioner, Dr. Zola Skweyiya; and HE the Ambassador of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Mr Pim Waldeck. Standing behind them is Mr James Farrell, Director, Arena Books, publisher of Knot of Stone. Those present but not on the photo include: HE Mr João de Vallera, Ambassador of Portugal; Professor Jack Lohman, Director of the Museum of London; Emeritus Professor Malyn Newitt, Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at King’s College London; Mr Steven O’Brien, Editor of The London Magazine: a Review of Literature and the Arts; Mrs Ellen Berends, wife of the author; Mr Jan van Weijen, Cultural Counsellor of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and his colleague Mrs Ciska Dijk, Attache Education and Literature.

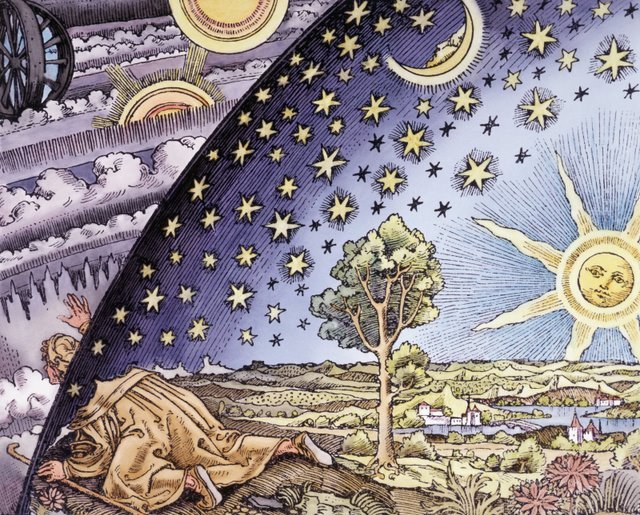

A sixteenth-century style woodcut thought to be made for the French astronomer Camille Flammarion, 1888.

A sixteenth-century style woodcut thought to be made for the French astronomer Camille Flammarion, 1888.

Before writing I asked myself: “What does a writer do on reaching the limits of the historical record?”

As our illustrious guest Professor Malyn Newitt once said: “The history of Portuguese expansion is at once very well known and hardly known at all.” Today I wish to say with him that “the history of South Africa’s first battle is at once very well known and hardly known at all”.

In fact, the official account of Almeida’s murder is full of gaps and inconsistencies; and those documents that do exist were written a century or two after his death—long after any witnesses could question the records. Moreover, no one ever stopped to challenge the account, at least not officially. Nor did anyone ask if there had been foul play; such as mutiny or assassination?

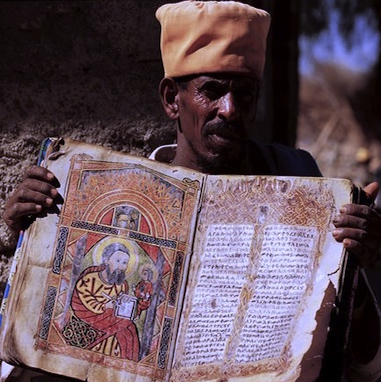

When I began writing Knot of Stone, several new or alternative sources came my way; such as legends, dreams, visions and oral histories. This may sound strange to a European ear, but having come from museums steeped in various African traditions, this was not at all odd for me. I am comfortable working with those for whom legends, rituals and sangomas play a significant role. For me, “ancestral” memory should be spoken and heard. It is often the only source we have left. As the old African proverb says: “When an old man dies, a library is lost.”

When I began writing Knot of Stone, several new or alternative sources came my way; such as legends, dreams, visions and oral histories. This may sound strange to a European ear, but having come from museums steeped in various African traditions, this was not at all odd for me. I am comfortable working with those for whom legends, rituals and sangomas play a significant role. For me, “ancestral” memory should be spoken and heard. It is often the only source we have left. As the old African proverb says: “When an old man dies, a library is lost.”

I know oral/oracular sources are difficult to accept, especially in western societies where these have waned in favour of empirical knowledge, making inclusion of the “ancestral voices” both challenging and thought provoking. It is for this reason that I chose the novel form over that of the travel journal, biography or monograph.

With its unique and peculiar mix of sources, Knot of Stone proposes that Almeida’s death was not simply the result of a local skirmish—but also caused by political intrigues back in Europe, thus binding developments in Southern Africa to Western Europe. Furthermore, the assassination attempt on Almeida and the political leadership since Nelson Mandela are, ultimately, two ends of the same knotted rope in South African history. Now is not the time for this, but see Chapter 94 (pp.418-427).

With its unique and peculiar mix of sources, Knot of Stone proposes that Almeida’s death was not simply the result of a local skirmish—but also caused by political intrigues back in Europe, thus binding developments in Southern Africa to Western Europe. Furthermore, the assassination attempt on Almeida and the political leadership since Nelson Mandela are, ultimately, two ends of the same knotted rope in South African history. Now is not the time for this, but see Chapter 94 (pp.418-427).

Writing this book was a challenge myself and tested my ideas and beliefs. I have no doubt that it will, in turn, challenge others to be receptive to re-reading and re-inscribing events in new and alternative ways.

Nicolaas Vergunst

Nicolaas, congratulations to you for finishing the book and to Ellen for supporting you on this journey. We look forward to seeing you both in Cape Town at the launch, and obviously to reading the book.

Congratulations, Nicolaas. Great to read your blog. Can’t wait for the book!

Hope the launch is spectacular. Thinking of you.

Bravo!

Today we launch our new Knot of Stone video clip.

Music composed by Nellis Du Biel, see The bar at the end of the world.

Helen and I would like to read your book. How do we find a copy?

Ah, Greg, what a surprise hearing from you after all this time—and to see pics of Helen, Melanie and Alex thirty-five years on! If you saw the new video you’ll have seen that the music was by Nellis, also from the same place and time in our lives. I’m planning the Cape Town launch for early next year but, for now, recommend you order Knot of Stone online.

Till then, take care.

Nice video clip. Love Nellis’ music.

Good Gracious ….accolades!

I just love the variety of pics (and connections) you have managed to find. When is your SA launch planned?

It is so lovely ! I’m very happy to see your pictures.