This paper was written for the CHAM (Centre for Humanities) conference at the University of Lisbon, 17-19 July 2019, and presented to an audience drawn primarily from South Africa, Zimbabwe and Egypt.

This paper was written for the CHAM (Centre for Humanities) conference at the University of Lisbon, 17-19 July 2019, and presented to an audience drawn primarily from South Africa, Zimbabwe and Egypt.

Good morning. I am a South African-born author living in the Netherlands. This paper draws on research for my book Knot of Stone and several subsequent online postings.

While researching the obscure death of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida at the Cape of Good Hope—notably the first recorded murder in the annals of South African history—I found myself using traditional knowledge sources to fill in where the historical record was either silent or gave conflicting accounts. Today I wish to show how the ancestral voices (spirit messages) can be used to fill existing gaps, reveal new links and offer fresh insights.

To this end my paper examines several spirit messages, received intermittently between 1996–2018, that draw attention to the political leadership of South Africa and Zimbabwe: from former presidents Nelson Mandela and Robert Mugabe to current presidents Cyril Ramaphosa and Emmerson Mnangagwa. According to the ancestors, these men come from a time/place in Africa’s past that continues to shape their conflicts and achievements. Theirs is a karmic drama in which the transfer of power and transition to democracy may be seen as re-enactments of events in ancient Egypt c.1292BCE and pre-colonial Zululand c.1828, respectively.

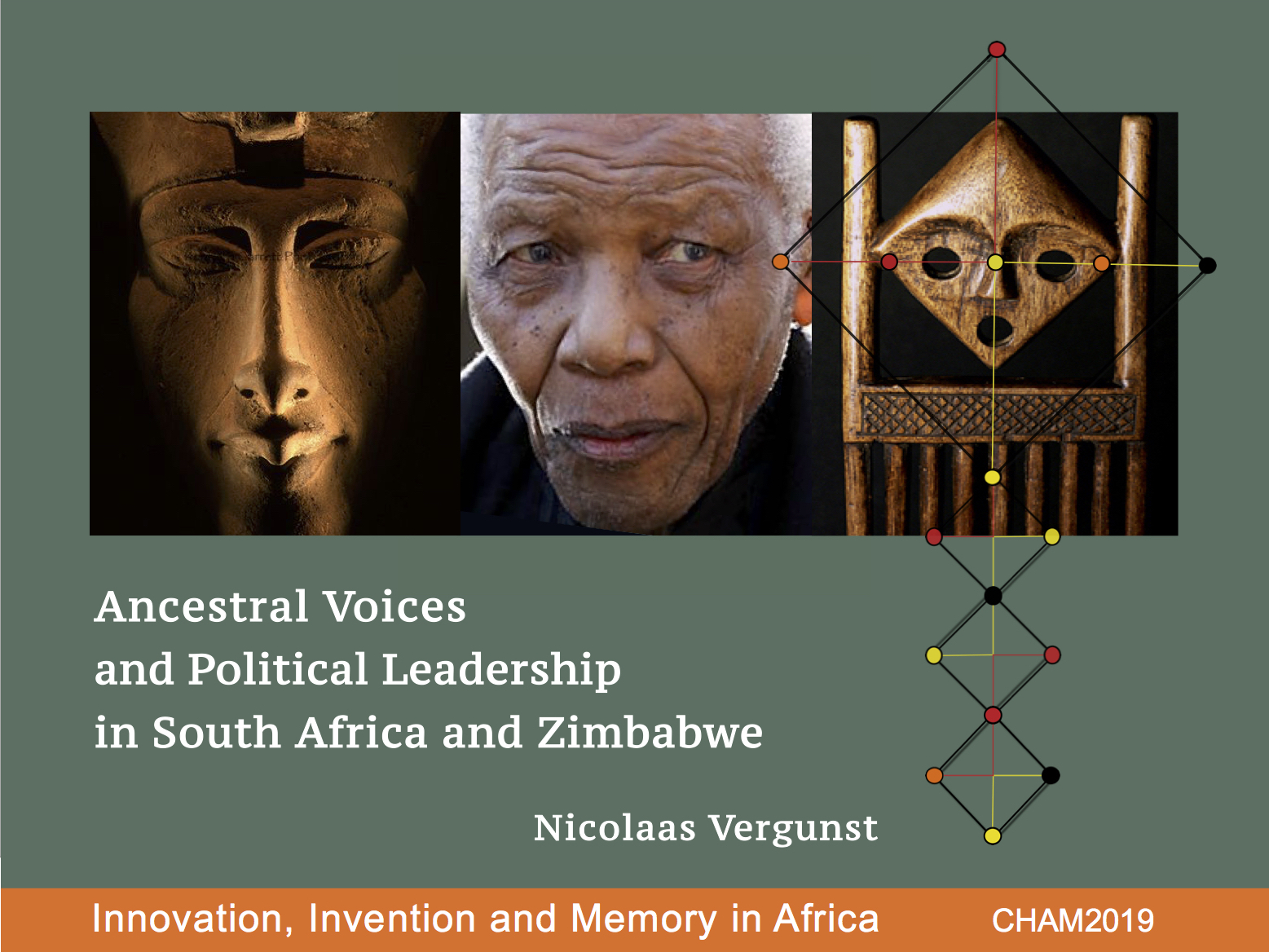

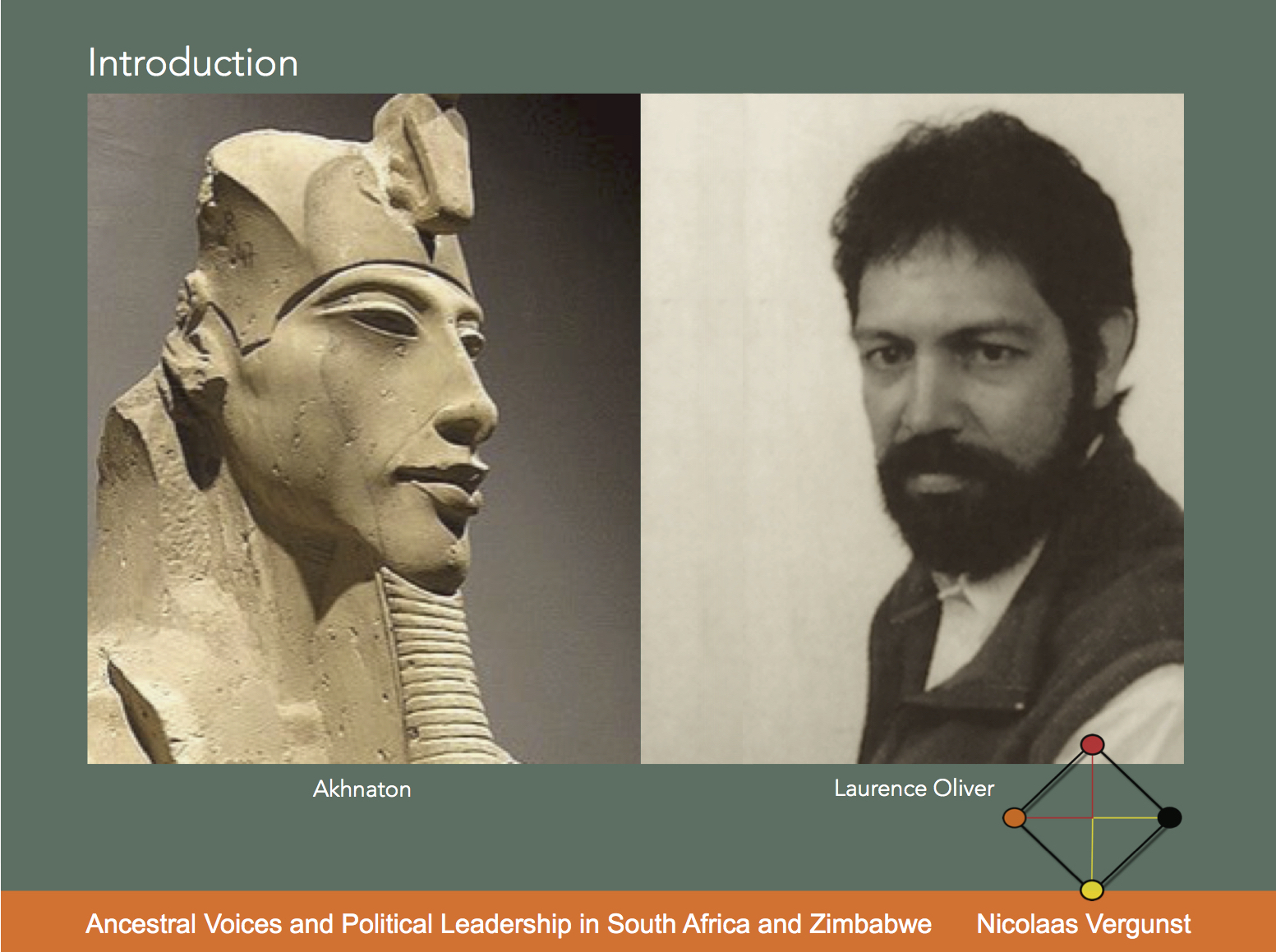

Among the ancestral spirits that have communicated with us is one who identifies himself as Akhnaton or Akhenaten (spellings vary), the much-maligned heretic pharaoh, who claims rivalry between his ministers and the old priesthood set the stage for the conflicts under apartheid and its ensuing power struggle. The message was received unexpectedly by clairaudient dictation and transcribed by Dr Laurence Oliver, a healer and health-care worker from Cape Town, in 1996. The entire transmission was published as The Message of Akhenaton (2001) and is not intended to reflect the personal or political views of its recipient and publisher.1

Among the ancestral spirits that have communicated with us is one who identifies himself as Akhnaton or Akhenaten (spellings vary), the much-maligned heretic pharaoh, who claims rivalry between his ministers and the old priesthood set the stage for the conflicts under apartheid and its ensuing power struggle. The message was received unexpectedly by clairaudient dictation and transcribed by Dr Laurence Oliver, a healer and health-care worker from Cape Town, in 1996. The entire transmission was published as The Message of Akhenaton (2001) and is not intended to reflect the personal or political views of its recipient and publisher.1

According to the message Akhnaton, “The unfinished story of my time has found its sequel in the unfolding story of your country, and many of the key figures of the drama that centered on me in those tragic days have arisen among you…”. Historians currently date the end of the 18th Dynasty, that is, from the reign of Akhnaton to Horemheb, as c.1350–1292BCE (alternatively c.1440–1380BCE).

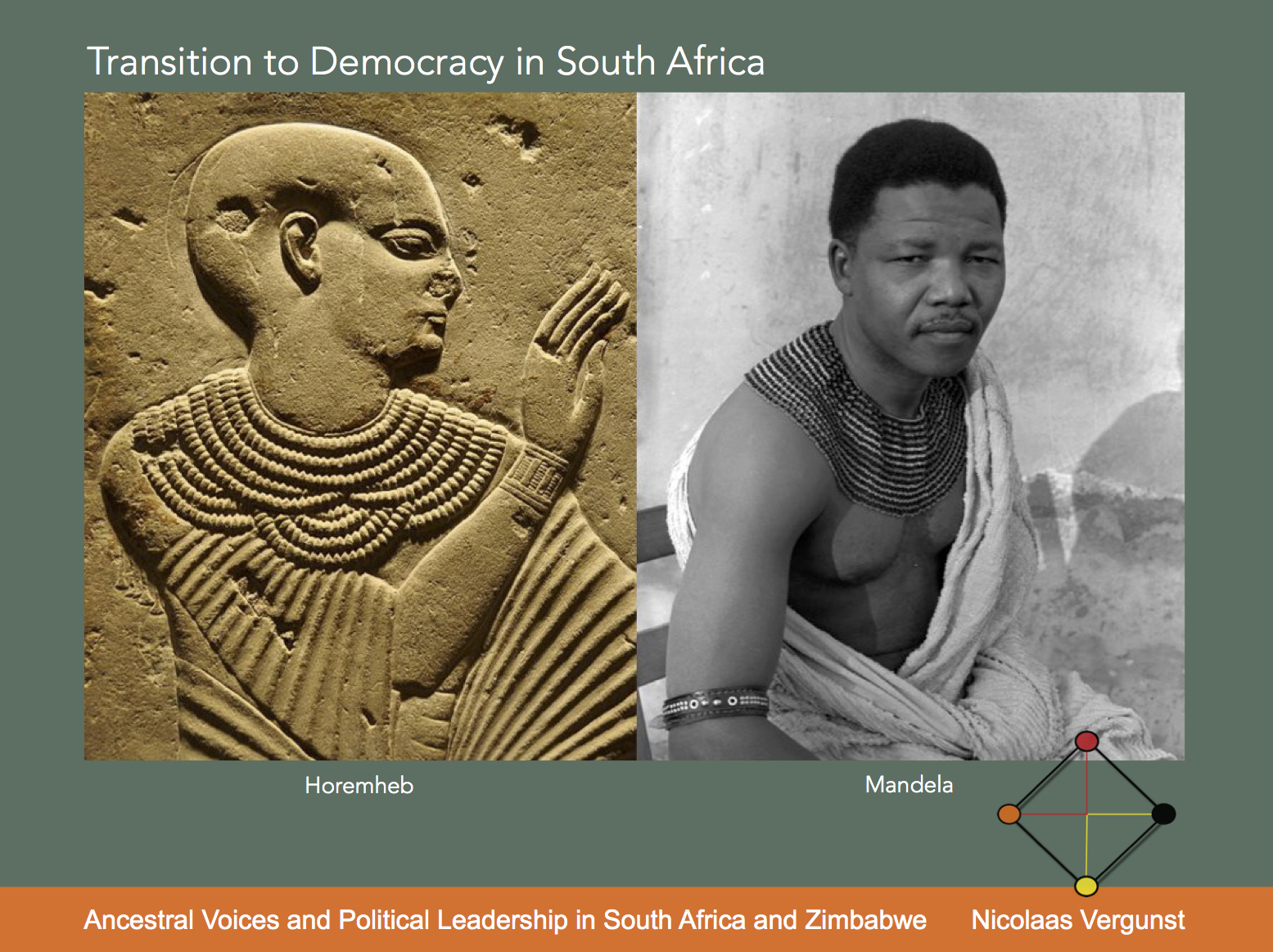

The relief sculpture of Horemheb is from a tomb pillar at Saqqara, c.1307BCE. The photograph was taken when Mandela was in hiding, c.1961, which is why a bedspread and not a traditional blanket was used to cover his left shoulder (a custom reserved for amaXhosa chiefs). Note the beaded neckpiece worn by both Horemheb and Mandela.

The relief sculpture of Horemheb is from a tomb pillar at Saqqara, c.1307BCE. The photograph was taken when Mandela was in hiding, c.1961, which is why a bedspread and not a traditional blanket was used to cover his left shoulder (a custom reserved for amaXhosa chiefs). Note the beaded neckpiece worn by both Horemheb and Mandela.

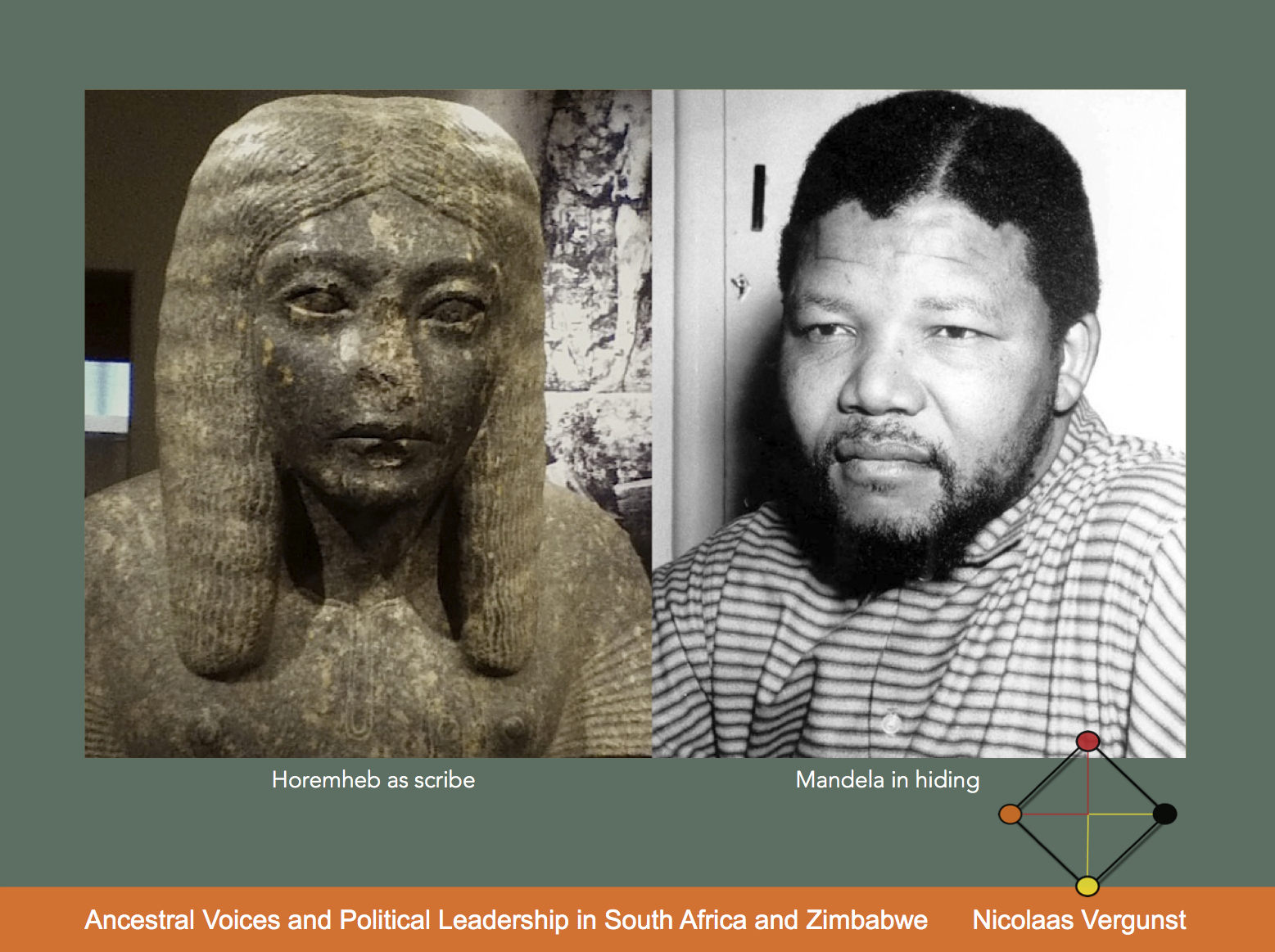

The message claims that Horemheb and Mandela are linked across the ages. Unknown to history, Horemheb was born a commoner and rose to power as commander-in-chief of Akhnaton’s army.2 Mandela, on the other hand, tells us that he learnt the art of stick fighting as a herdboy and rose to power as co-founder and first commander of Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), then the military wing of the African National Congress.3

Mandela’s given name, Rolihlahla, literally means “tree shaker” or “trouble maker”. Both Horemheb and Mandela shook their nation and led an armed revolution. Both came to office through popular uprisings and set about transforming old power structures and curbing abuses by the state. Both men appointed new judges, re-established order and ruled a divided people. Both repudiated slavery or forced labour and extended the right of citizenship to formerly oppressed and exploited migrants. Both initiated a culture of reconciliation that did not last beyond their deaths. And both died having two tombs prepared for them.

The statue of Horemheb dates from the 2ndC BCE and resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The photograph of Mandela was taken while he was on the run and staying in Wolfie Kodesh’s flat in Johannesburg c.1961. Courtesy BBC.

The statue of Horemheb dates from the 2ndC BCE and resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The photograph of Mandela was taken while he was on the run and staying in Wolfie Kodesh’s flat in Johannesburg c.1961. Courtesy BBC.

According to the message, their shared history is more than an analogy: “I, Akhnaton, would have you know that Horemheb is none other than your Nelson Mandela. Fourteen centuries before your present age, Horemheb was my military commander-in-chief and had warned me of the weakening political situation in my empire. Regrettably, I ignored his advice and forbade any military action. Withdrawn and out of touch with the populace, I concerned myself only with issues of religious revolution—the monotheist religion of Aton.”

To this end, Akhnaton built a new capital, Akhetaton, so named for the god (now known as Amarna), and moved his court out of Thebes (modern Luxor). The celebrated 18th dynasty finally came to an end under Horemheb whose rule as military-usurper had endured for twenty-seven years. It is in consequence of this, notes Akhnaton, that Mandela would endure imprisonment for twenty-seven years and, eventually, become the liberator of his oppressed people.4

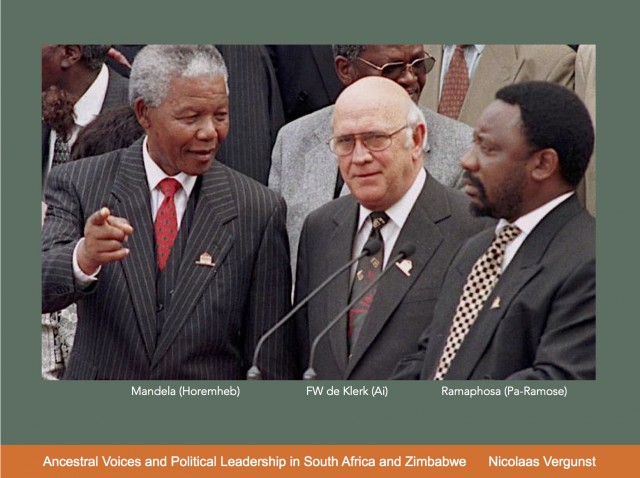

Three South African presidents cut from one cloth? From a karmic perspective, Nelson Mandela (presidential term 1994–1999), FW de Klerk (1989–1994) and Cyril Ramaphosa (2018– ) are said to be former allies and successive pharaohs, namely Horemheb, Ai and Pa-Ramose (later Ramses I). Besides serving as Akhnaton’s vizier, Ai also acted as godfather to Akhnaton’s son, Tutankhaton (later Tutankhamen). During the upheavals that followed Akhnaton’s death, Ai stood up against the revolt and called for reconciliation to restore peace and stability, promising prosperity under the boy-king. According to Akhnaton’s message, it takes a man of courage and moral stature to put his country before himself: “Think not that Ai was treacherous or cowardly, for he did this not to save himself but to save Egypt.”5 While some historians will disagree, the same may be said of De Klerk who took the bold initiative and reset the course of history in South Africa.6

Three South African presidents cut from one cloth? From a karmic perspective, Nelson Mandela (presidential term 1994–1999), FW de Klerk (1989–1994) and Cyril Ramaphosa (2018– ) are said to be former allies and successive pharaohs, namely Horemheb, Ai and Pa-Ramose (later Ramses I). Besides serving as Akhnaton’s vizier, Ai also acted as godfather to Akhnaton’s son, Tutankhaton (later Tutankhamen). During the upheavals that followed Akhnaton’s death, Ai stood up against the revolt and called for reconciliation to restore peace and stability, promising prosperity under the boy-king. According to Akhnaton’s message, it takes a man of courage and moral stature to put his country before himself: “Think not that Ai was treacherous or cowardly, for he did this not to save himself but to save Egypt.”5 While some historians will disagree, the same may be said of De Klerk who took the bold initiative and reset the course of history in South Africa.6

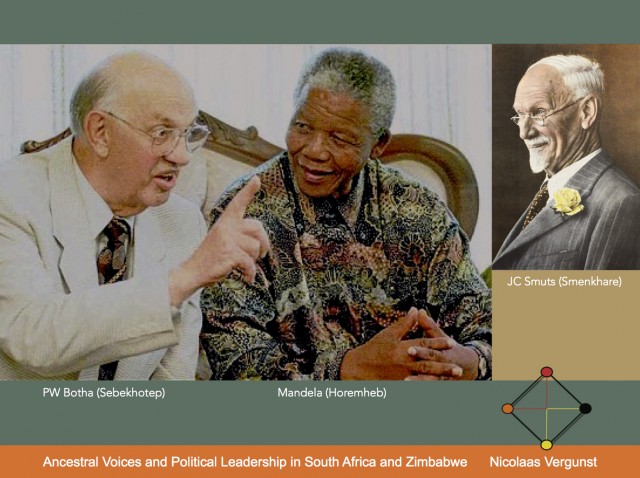

PW Botha and Nelson Mandela share a casual moment during Mandela’s presidency. Mandela often recalled their first meeting in 1989 when, as a prisoner, he was taken to president PW Botha’s office at Tuynhuys for a secret meeting. Mandela adds: “I remember he poured the tea himself. I was touched by the gesture. It was a simple sign of respect, unthinkable under apartheid.”

PW Botha and Nelson Mandela share a casual moment during Mandela’s presidency. Mandela often recalled their first meeting in 1989 when, as a prisoner, he was taken to president PW Botha’s office at Tuynhuys for a secret meeting. Mandela adds: “I remember he poured the tea himself. I was touched by the gesture. It was a simple sign of respect, unthinkable under apartheid.”

A fourth president, PW Botha (1978–1989), is said to have been Sebekhotep, high priest of the Amenite crocodile-god in Thebes. Ironically, Botha was nicknamed Groot Krokodil (“Great Crocodile”) for his tough and uncompromising apartheid politics. As Sebekhotep he rose in power to become pope of the rival Amenite religion, but was deposed for plotting the murder of young Tutankhamen. Sebekhotep was subsequently banished to the wilderness and never seen again. Similarly, Botha retired to the Wilderness, a small coastal town in South Africa, and was rarely seen in public again.7

In the chaos following Akhnaton’s death, his younger brother and brief successor, Smenkhare, bravely defended the capital Akhetaton against the onslaught unleashed by the Amenite priesthood. Here Akhnaton adds: “I would have you know that Smenkhare reappeared in your country as its past prime minister, General Jan Christian Smuts, who was similarly unable to stave off the ominous rise to power of the Nationalist regime of Afrikanerdom.”8

Akhnaton’s chief sculptor Bek orchestrated a renaissance in sculpture to express the religious revolution with which his pharaoh had become obsessed. Here Akhnaton adds that Bek is none other than Thabo Mbeki, also a former president of South Africa (1999–2008), who inaugurated the so-called African Renaissance.10

Akhnaton’s chief sculptor Bek orchestrated a renaissance in sculpture to express the religious revolution with which his pharaoh had become obsessed. Here Akhnaton adds that Bek is none other than Thabo Mbeki, also a former president of South Africa (1999–2008), who inaugurated the so-called African Renaissance.10

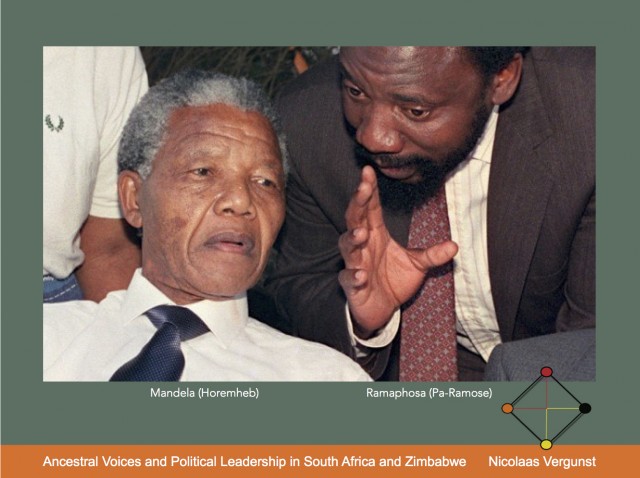

History tells us that Pharaoh Horemheb chose Pa-Ramose to be his successor in return for his loyalty, and because he himself was childless. Pa-Ramose had a son and grandson and could thus secure Egypt’s royal succession. As we now know, Ramaphosa had been Mandela’s first choice for successor too.11 From a karmic perspective, we could view Ramaphosa as the rightful heir once again. However, Ramaphosa was outmanoeuvred by Mbeki and had to wait a decade before becoming president. The Message of Akhnaton predates his presidency by over twenty years and illustrates how, at least in some cases, spirit messages may indicate what is yet to come.

History tells us that Pharaoh Horemheb chose Pa-Ramose to be his successor in return for his loyalty, and because he himself was childless. Pa-Ramose had a son and grandson and could thus secure Egypt’s royal succession. As we now know, Ramaphosa had been Mandela’s first choice for successor too.11 From a karmic perspective, we could view Ramaphosa as the rightful heir once again. However, Ramaphosa was outmanoeuvred by Mbeki and had to wait a decade before becoming president. The Message of Akhnaton predates his presidency by over twenty years and illustrates how, at least in some cases, spirit messages may indicate what is yet to come.

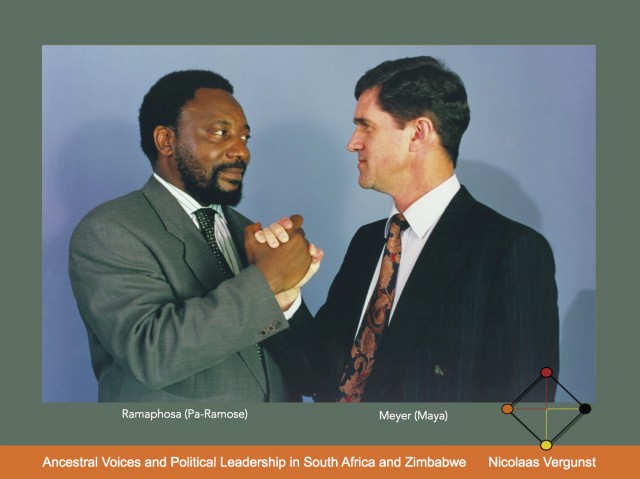

The photograph of Cyril Ramaphosa and Roelf Meyer was taken by David Goldblatt after the breakthrough negotiations in 1993. It is often noted that their secret meetings led to a lasting friendship. In this context we could say it is one that spans the ages.

The photograph of Cyril Ramaphosa and Roelf Meyer was taken by David Goldblatt after the breakthrough negotiations in 1993. It is often noted that their secret meetings led to a lasting friendship. In this context we could say it is one that spans the ages.

Akhnaton mentions two of his ministers who lived to serve under Ai and Horemheb, namely Pa-Ramose and Maya,12 adding that they returned to play their part as Mandela and De Klerk’s chief negotiators in the tumultuous early 1990s. These negotiations paved the way for the country’s first non-racial democratic election, after which Mandela was appointed president with De Klerk and Mbeki as his deputies.

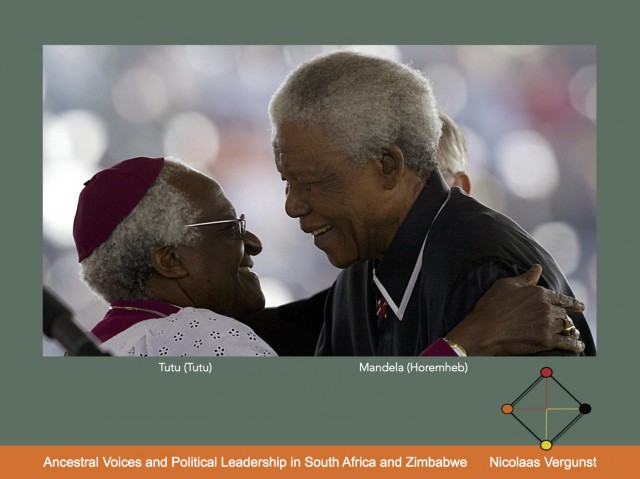

According to the pharaoh’s message, Horemheb warned Akhnaton that the continuing emigration of Egypt’s enslaved Hebrew population would set off a rebellion or, possibly, an invasion. The exodus was initiated by the pharaoh’s own cousin Osiraes, better known today as the biblical Moses, a high priest of Amen-Ra and Keeper of the Ark.13 Here Akhnaton continues: “Still, I refused to listen, preoccupied by my grandiose vision of a utopian church-state. Had it not been for the diplomatic initiatives of my minister of foreign affairs, Tutu, the eastern provinces may have seceded their independence. However, my political indifference was counterbalanced by Tutu’s tactful foreign policy, for he saved Egypt when I, alas, failed my people. It should be easy to guess that Tutu is the gracious and illustrious former archbishop, Desmond Tutu.”14

According to the pharaoh’s message, Horemheb warned Akhnaton that the continuing emigration of Egypt’s enslaved Hebrew population would set off a rebellion or, possibly, an invasion. The exodus was initiated by the pharaoh’s own cousin Osiraes, better known today as the biblical Moses, a high priest of Amen-Ra and Keeper of the Ark.13 Here Akhnaton continues: “Still, I refused to listen, preoccupied by my grandiose vision of a utopian church-state. Had it not been for the diplomatic initiatives of my minister of foreign affairs, Tutu, the eastern provinces may have seceded their independence. However, my political indifference was counterbalanced by Tutu’s tactful foreign policy, for he saved Egypt when I, alas, failed my people. It should be easy to guess that Tutu is the gracious and illustrious former archbishop, Desmond Tutu.”14

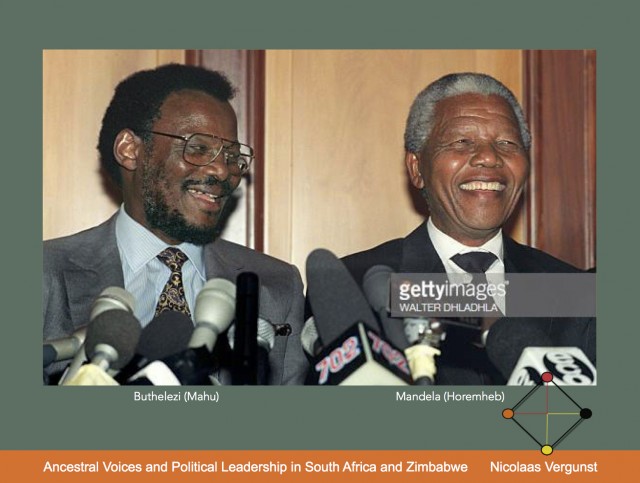

Approaching the end of his message, Akhnaton explains that several other ministers and court officials, some ever loyal to him, returned as the black leadership of South Africa—or as whites aligned to the freedom struggle—whereas the priests of Amen-Ra became leaders of the old white regime. Here are some further examples: Mahu, Akhnaton’s chief-of-police, returned as Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party. Hani, Akhnaton’s royal secretary and foreign ambassador, came back as Chris Hani, chief-of-staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe. Tragically, Hani was assassinated in both these lives. Akhnaton’s chief minister and priest at On (Heliopolis), cult centre of the sun god Ra, was Aper-El and is linked to Chief Albert Luthuli, a true man of peace.15 Pa-Aton, also a scribe and priest from On, is associated with Alan Paton, author of Cry the Beloved Country.

Approaching the end of his message, Akhnaton explains that several other ministers and court officials, some ever loyal to him, returned as the black leadership of South Africa—or as whites aligned to the freedom struggle—whereas the priests of Amen-Ra became leaders of the old white regime. Here are some further examples: Mahu, Akhnaton’s chief-of-police, returned as Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party. Hani, Akhnaton’s royal secretary and foreign ambassador, came back as Chris Hani, chief-of-staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe. Tragically, Hani was assassinated in both these lives. Akhnaton’s chief minister and priest at On (Heliopolis), cult centre of the sun god Ra, was Aper-El and is linked to Chief Albert Luthuli, a true man of peace.15 Pa-Aton, also a scribe and priest from On, is associated with Alan Paton, author of Cry the Beloved Country.

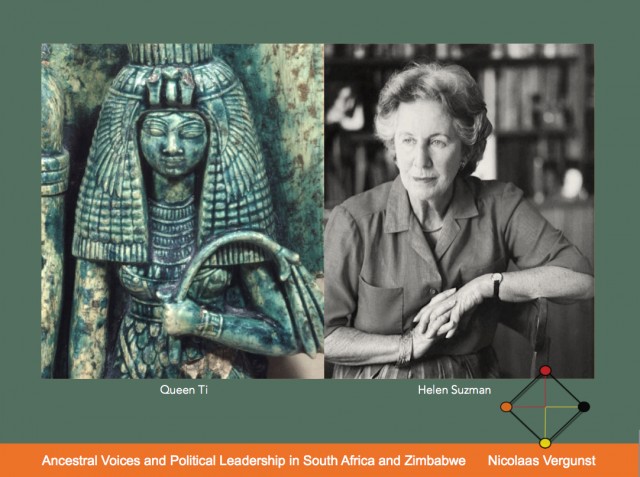

Last but not least, Akhnaton adds: “You are wondering in your mind about the women? Were none worthy? Then, as now, men regrettably overshadowed women. But there was one woman who could have ruled Egypt better than any man, had she been given the chance. She was my dear and revered mother, Queen Ti, who returned as Helen Suzman.”16

Last but not least, Akhnaton adds: “You are wondering in your mind about the women? Were none worthy? Then, as now, men regrettably overshadowed women. But there was one woman who could have ruled Egypt better than any man, had she been given the chance. She was my dear and revered mother, Queen Ti, who returned as Helen Suzman.”16

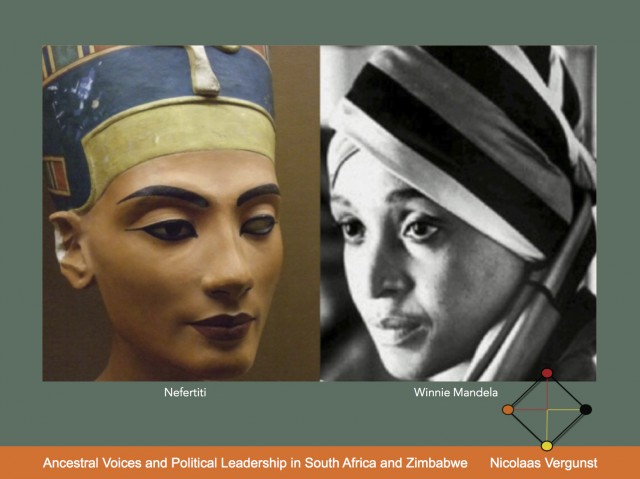

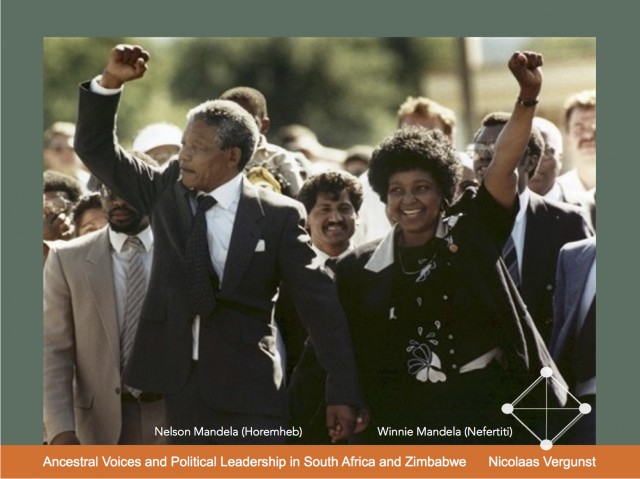

As for Akhnaton’s chief wife and consort, Nefertiti: “My queen-wife, a foreign princess from the kingdom of Mitanni in the Tigris Valley, was called Nefertiti on account of her beauty. Her name means ‘beautiful woman’ and she had been chosen as a new wife for my father, but their marriage was never consummated due to his ill-health. She is known today as Winifred, or simply Winnie, the former wife of Nelson Mandela.”17

The iconic bust of Nefertiti by Thutmose, 1345BCE, found in the sculptor’s workshop at Amarna, is now in the Neues Museum, Berlin.18 The portrait of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela dates from 1975. Courtesy Avusa. The reputations of both women were marred by allegations of abduction involving young boys: the kidnapping of Stompie Moeketsi19 has its parallel in the abduction of young Tutankhaton.

The iconic bust of Nefertiti by Thutmose, 1345BCE, found in the sculptor’s workshop at Amarna, is now in the Neues Museum, Berlin.18 The portrait of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela dates from 1975. Courtesy Avusa. The reputations of both women were marred by allegations of abduction involving young boys: the kidnapping of Stompie Moeketsi19 has its parallel in the abduction of young Tutankhaton.

“Unbeknown to official history,” says Akhnaton, “I had a son by a beloved mistress Hareth, who was also my court singer. The child was called Tutankhaton, destined to rule as Tutankhamun. Nefertiti was exceedingly jealous, fearing she would be deposed as queen-wife in favour of the child’s mother. She became disloyal and treacherous, abducting Tutankhaton and taking him to Thebes. Here he was raised as a royal priest of Amen-Ra, like Osiraes [Moses] before him, so when the time came he would be presented as my successor, reclaiming their position as the state religion. Hence I am called the Heretic Pharaoh.”20

Akhnaton again: “Tutankhaton’s mother was heartbroken by the loss of our son and drowned herself in the Nile. My own heart broke and I never smiled again. As the years passed my health began to fail slowly, then rapidly, so that I knew I was dying from grief and disillusionment. Shortly after this I, Akhnaton, died in despair.”21

Akhnaton again: “Tutankhaton’s mother was heartbroken by the loss of our son and drowned herself in the Nile. My own heart broke and I never smiled again. As the years passed my health began to fail slowly, then rapidly, so that I knew I was dying from grief and disillusionment. Shortly after this I, Akhnaton, died in despair.”21

Akhnaton’s death triggered widespread rioting in due time followed by a reign of terror. During the ensuing chaos Horemheb kept a watchful eye over the devious and unrepentant Nefertiti but—as would happen again with Winnie—she was left to go unpunished. He loathed her with a vengeance and, finally, had her executed. Karmically speaking, Horemheb’s hatred of Nefertiti had to be expiated in his troubled marriage to her during their last life: “For the law of karma requires hatred to be met again—as tragic love.”22

Akhnaton concludes: “To my ministers I say: May you remember who you are, and heed the lessons taught to you by my life and times as Akhnaton. May you fulfil the best of my ideals and triumph over the worst of my tragedies. In spirit I, Akhnaton, keep watch over this country to see that the mistakes of the eternal past are not repeated. A great future awaits you in due time…”.23

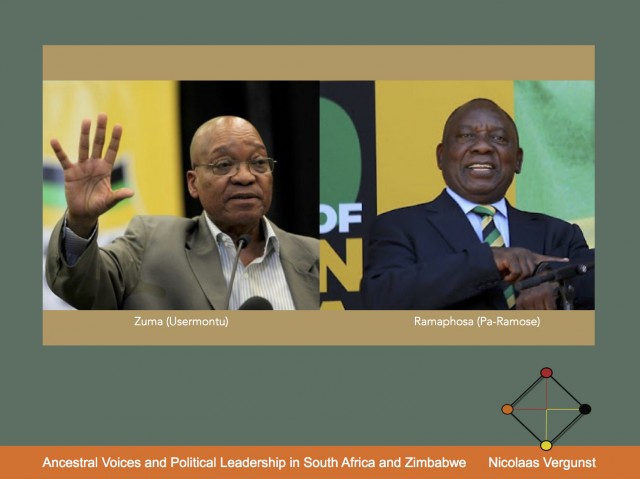

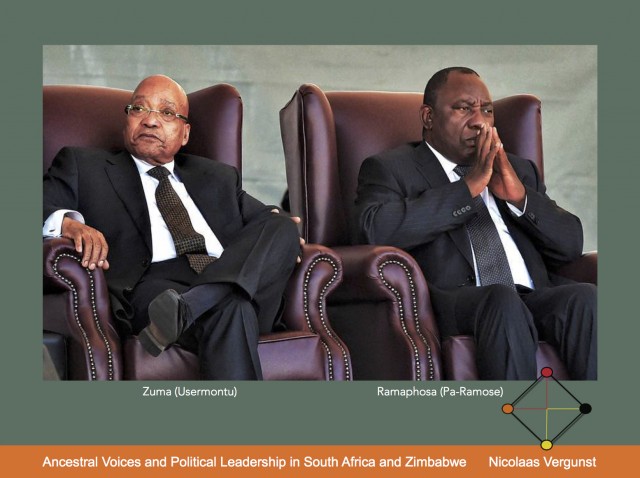

However, the situation would deteriorate over the next two decades. A subsequent set of messages — transmitted when the devious Jacob Zuma defeated president Thabo Mbeki — allege that Zuma had been a corrupt court official called Ahmed or Ahmose.24

However, the situation would deteriorate over the next two decades. A subsequent set of messages — transmitted when the devious Jacob Zuma defeated president Thabo Mbeki — allege that Zuma had been a corrupt court official called Ahmed or Ahmose.24

Furthermore, Zuma had been an Amenite priest and partisan to Nefertiti’s conspiracy to install the abducted Tutankhaton as a puppet pharaoh. With their success he became vizier of the South and is recorded in history as Usermontu, so named after the war god Montu, one of the Amenite pantheon. The same conspirators later saw to the murders of Tutankhamen and Ai.25

According to Oliver, Usermontu was responsible for the defacement and desecration of all monuments and records relating to Akhnaton, Smenkhare and Ai, and to some extent Tutankhamen, while propagating Horemheb (rather than Akhnaton) as the legitimate successor of Amenhotep III. Ironically, in his zealous dismantling of Akhnaton’s capital city, Usermontu undid the work of Bek, its chief architect and master mason. More recently, as if it were unfinished business, Zuma trashed the legacy of Mbeki once again.26 If these allegations are true, then Zuma and Ramaphosa should have known each other before, surely?

Well, it appears that when Horemheb usurped power he retained Usermontu as vizier of the South — to appease and maintain peace with the Amenite regime — and duly appointed his second-in-command Pa-Ramose as vizier of the North to play a “counterbalancing role” in state affairs.27

Well, it appears that when Horemheb usurped power he retained Usermontu as vizier of the South — to appease and maintain peace with the Amenite regime — and duly appointed his second-in-command Pa-Ramose as vizier of the North to play a “counterbalancing role” in state affairs.27

Today’s struggle between Zuma and Ramaphosa would seem to be a re-enactment of their past. If what happened then is anything to go by, Ramaphosa could usher in an era that reaches new heights, a renaissance of Egypt’s glorious Ramesside dynasty. Or, like Ramses I, his term in office may be short and unremarkable.

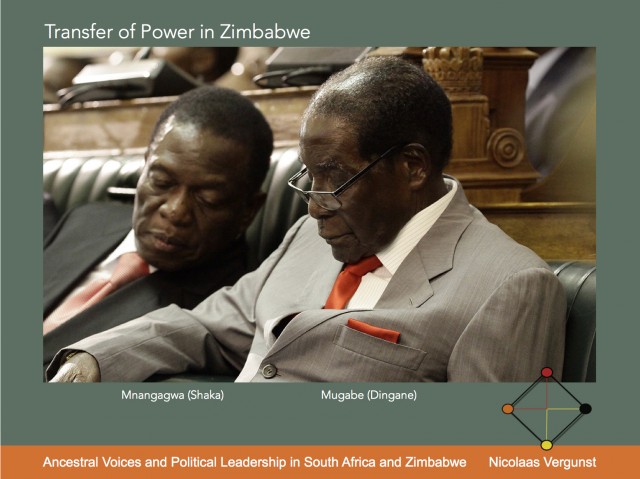

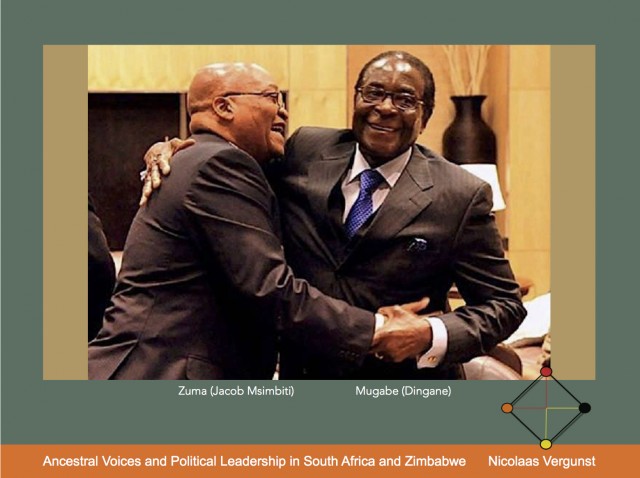

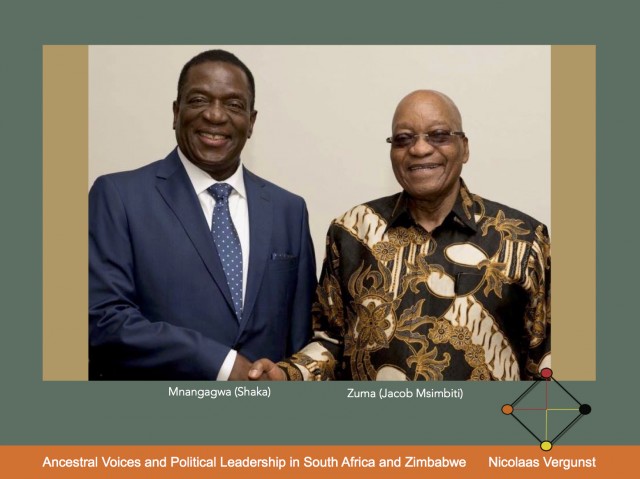

More recently, following the 2017 coup d’état in Zimbabwe, additional information was transmitted that claims Emmerson Mnangagwa and Robert Mugabe had once been half-brothers and successive rulers of the Zulu kingdom, namely Shaka (c.1787–1828) and Dingane (1795–1840), respectively.28

More recently, following the 2017 coup d’état in Zimbabwe, additional information was transmitted that claims Emmerson Mnangagwa and Robert Mugabe had once been half-brothers and successive rulers of the Zulu kingdom, namely Shaka (c.1787–1828) and Dingane (1795–1840), respectively.28

According to old tribal lore and early travel journals, Dingane conspired with members of his family to have Shaka killed. Mbopa, an inDuna (advisor or aide) with constant access to the king, was chosen to carry out the deed. Mbopa was willing but lacked courage until, uncannily, Shaka dreamt he was dead and Mbopa had a new master. Alarmed when he heard this, Dingane decided to act swiftly and kill Shaka that same day.29

History lets us know that Shaka was assassinated by his half-brothers Dingane and Mhlangana, aided by the inDuna Mbopa. While all three fled afterwards, the two brothers later claimed to have killed Shaka because of the increasing brutalities and incessant carnagefollowing the death of Shaka’s mother, Nandi. However, tensions over their spoils (cattle from the royal herd) arose between them and within weeks Dingane had his younger brother Mhlangana murdered. Probably by Mbopa.

History lets us know that Shaka was assassinated by his half-brothers Dingane and Mhlangana, aided by the inDuna Mbopa. While all three fled afterwards, the two brothers later claimed to have killed Shaka because of the increasing brutalities and incessant carnagefollowing the death of Shaka’s mother, Nandi. However, tensions over their spoils (cattle from the royal herd) arose between them and within weeks Dingane had his younger brother Mhlangana murdered. Probably by Mbopa.

To carry out Shaka’s assassination, the conspirators had taken advantage of the armies’ absence and on its return, with Mhlangana now dead, Dingane promised the stunned troops a season of rest, the right to marry and the enjoyment of their booty. Most accepted these terms and, as heir apparent, allowed Dingane to assume power. Those found to oppose the succession were killed.30

For his part in the assassination, the law of karma dictated that Mugabe surrender political power to Mnangagwa. Thus, as an irony of history, their contemporary order of succession was reversed. As Akhnaton explains, “the workings of karma have a way of turning events around to balance things out.”31

This photo shows president Mnangagwa pledging himself to holding a democratic election after deposing his long-term comrade and friend Robert Mugabe. Considering that Mugabe had assassinated Mnangagwa in their former lives, the latter’s commitment to a “free, credible, fair and indisputable” election can be seen as an extraordinary karmic gesture. It is also what any smart politician would say under scrutiny.

This photo shows president Mnangagwa pledging himself to holding a democratic election after deposing his long-term comrade and friend Robert Mugabe. Considering that Mugabe had assassinated Mnangagwa in their former lives, the latter’s commitment to a “free, credible, fair and indisputable” election can be seen as an extraordinary karmic gesture. It is also what any smart politician would say under scrutiny.

It is well documented that the struggle for Zimbabwe, 1966-80, was fought by guerrillas and spirit mediums of the Shona royal ancestors, the bringers of rain.32 Both Mugabe and Mnangagwa are also Shona. Notably, the practice of using spirit mediums (maGombwe or n’angas) continues amongst senior politicians today.33

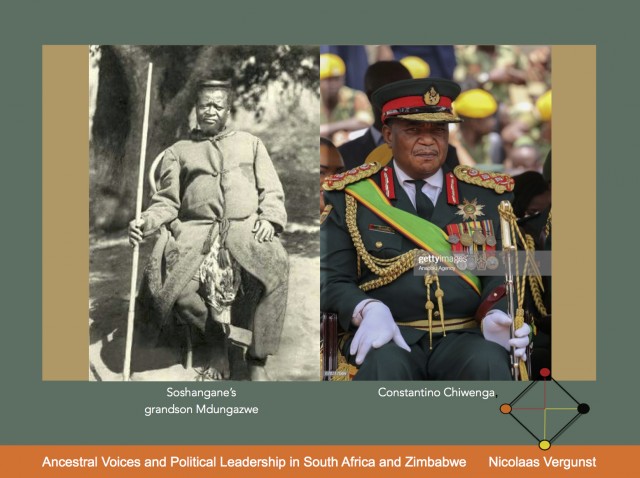

Lastly, two other contemporaries from the Shakan era are worth mentioning. The first is Chief Soshangane (c.1780–c.1858), who fled Shaka’s raging army and settled in Portuguese East Africa, modern-day Mozambique. Through one bloody conquest after another Soshangane subjugated and assimilated the indigenous tribes, and founded the so-called Gaza Empire. Soshangane is said to be current deputy-president of Zimbabwe, Constantino Chiwenga,34 a retired army general and minister of defence. It is rumoured that Chiwenga wants to create another empire.35 Who knows if he’ll defy his old nemesis again?

Lastly, two other contemporaries from the Shakan era are worth mentioning. The first is Chief Soshangane (c.1780–c.1858), who fled Shaka’s raging army and settled in Portuguese East Africa, modern-day Mozambique. Through one bloody conquest after another Soshangane subjugated and assimilated the indigenous tribes, and founded the so-called Gaza Empire. Soshangane is said to be current deputy-president of Zimbabwe, Constantino Chiwenga,34 a retired army general and minister of defence. It is rumoured that Chiwenga wants to create another empire.35 Who knows if he’ll defy his old nemesis again?

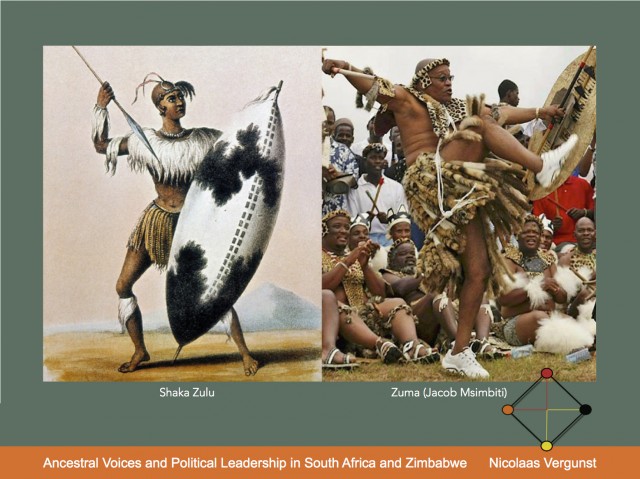

President Zuma is shown here performing a traditional Zulu dance during the wedding to his fourth wife at his home in KwaZulu-Natal, 2008. Courtesy Reuters.

President Zuma is shown here performing a traditional Zulu dance during the wedding to his fourth wife at his home in KwaZulu-Natal, 2008. Courtesy Reuters.

The second figure from that time is one Jakot or Jacob Msimbiti, a notorious amaXhosa cattle thief and Robben Island convict. As fate would have it, he was released to serve as an interpreter for English traders in Natal and, after several daring escapades, was present at kwaBulawayo when Shaka was assassinated. Msimbiti had arrived at the royal kraal four years before and, on hearing of his varied and adventurous journeys, including that he had twice survived a capsized boat, Shaka nicknamed him Hlambamanzi (the “Swimmer”) and retained him as his royal aide, adviser and interpreter.36

The ubiquitous Jacob appears to have switched allegiance to Dingane since, after the assassination, it was he who informed the traders at Port Natal that they had nothing to fear since the new king invited them to trade skins and ivory. Acting as Dingane’s ambassador, Jacob promised the band of Englishmen renewed peace and prosperity in Zululand. His former masters were all too suspicious, however, as he had openly opposed the presence of white hunter-traders in Natal before. They were also wary of his criminal record and widespread reputation as a liar and schemer—a reputation he also held among his compatriots too—and pressed Dingane to “put him on trial for deceit and duplicitous conduct”. After Jacob was caught stealing again from the royal herd, Dingane lost his temper and ordered his execution. Jacob was hunted down by his arch-rival, John Cane, to whom Dingane later gave eighty cows from Jacob’s own herd. According to the ancestral voices, Jacob Msimbiti is Jacob Zuma today.37

The ubiquitous Jacob appears to have switched allegiance to Dingane since, after the assassination, it was he who informed the traders at Port Natal that they had nothing to fear since the new king invited them to trade skins and ivory. Acting as Dingane’s ambassador, Jacob promised the band of Englishmen renewed peace and prosperity in Zululand. His former masters were all too suspicious, however, as he had openly opposed the presence of white hunter-traders in Natal before. They were also wary of his criminal record and widespread reputation as a liar and schemer—a reputation he also held among his compatriots too—and pressed Dingane to “put him on trial for deceit and duplicitous conduct”. After Jacob was caught stealing again from the royal herd, Dingane lost his temper and ordered his execution. Jacob was hunted down by his arch-rival, John Cane, to whom Dingane later gave eighty cows from Jacob’s own herd. According to the ancestral voices, Jacob Msimbiti is Jacob Zuma today.37

As if history were repeating itself, Zuma was forced to step down as president of South Africa due to mounting theft and corruption charges. Some leopards never change their spots.

Finally, a last photo with which to round off: Few, if any of us, are aware of our past lives or the conflictual relationships we are here to work out. More so, most don’t even believe in the transmigration of souls. It is not the purpose of this paper to proselytise that point. Nor to judge those discussed above. As Akhnaton says: “It matters not who was who, who did what, or who was right and who wrong. What matters are the lessons to be learnt from one another.”38

Finally, a last photo with which to round off: Few, if any of us, are aware of our past lives or the conflictual relationships we are here to work out. More so, most don’t even believe in the transmigration of souls. It is not the purpose of this paper to proselytise that point. Nor to judge those discussed above. As Akhnaton says: “It matters not who was who, who did what, or who was right and who wrong. What matters are the lessons to be learnt from one another.”38

While pharaonic Egypt and modern South Africa are distinct from the rest of Africa, both share the continent’s underlying historical processes: centrally-imposed governments, demographic growth, urbanisation, liberation movements and independence struggles.39 Plus an age-old belief in ancestral spirits and recurrent lives.40 This paper has sought a synthesis between the two, that is, between historical realities and realities of the spirit, between the present and the past, and between the living and the dead.

While pharaonic Egypt and modern South Africa are distinct from the rest of Africa, both share the continent’s underlying historical processes: centrally-imposed governments, demographic growth, urbanisation, liberation movements and independence struggles.39 Plus an age-old belief in ancestral spirits and recurrent lives.40 This paper has sought a synthesis between the two, that is, between historical realities and realities of the spirit, between the present and the past, and between the living and the dead.

As stated at the outset, this presentation was meant to fill old gaps, reveal new links and offer fresh insights. I hope this paper has fulfilled that purpose. If so, I thank our ancestors for this privilege, you for your patience, and the conference organisers for this opportunity.

Nicolaas Vergunst

A fine mix of history, politics, memory and poetics.

Good meaty stuff, Nicolaas, and now on record in an important arena. We work and leave signposts for the future, not necessarily for these (dissolving) times.

I read your paper with much interest. As with your book Knot of Stone I am again fascinated by what the ancestral voice lets us see. And I find the similarities between the photos most striking.

RIP FW de Klerk, vizier, godfather and courageous diplomat: “Think not that he was treacherous or cowardly, for he did this not to save himself but to save his country.” Cited by Laurence Oliver, Out of Eden, 2001, p.131. See also Knot of Stone, pp.418-422.

For a succinct and concise overview of De Klerk’s contested career, including his posthumous farewell, read/listen to Ray Hartley’s article in BusinessDay (11.11.2021). https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/2021-11-11-ray-hartley-de-klerk-was-a-leader-at-war-with-his-history