This paper traces the recurrence of several Classical themes in an age of Portuguese overseas expansion. It was written for the CHAM (Centre for Humanities) conference at the University of Lisbon, 12–15 July 2017, and draws on research used in Knot of Stone.

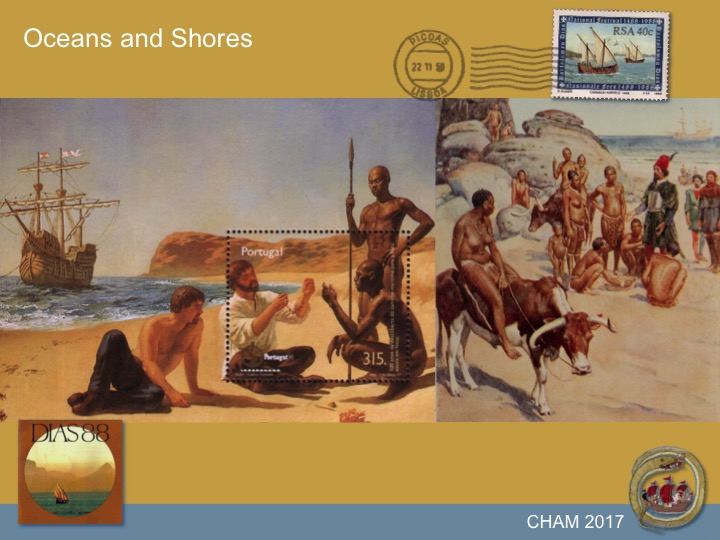

The III CHAM conference theme, Oceans and Shores, takes me back three decades, to 1987–1988, when I wrote my first essay for a literary competition entitled ‘Portuguese discoveries and the consequences for Africa’.1 The contest coincided with the Dias 88 quincentenary and was adjudicated by scholars from the universities of Lisbon and Cape Town. I saw my essay as an opportunity to present new insights into the death of Dias’ compatriot, Viceroy D’Almeida, and to revisit its knock-on effect in the land of my birth.2

Thirty years later I find myself still writing about first encounters on the beach—that intertidal zone between land and sea—where local and classical interpretations continue to wash up against each other. It seems the problems we face today are no less sombre, no less sensitive and no less ambivalent than they were decades or even centuries ago.3

Thirty years later I find myself still writing about first encounters on the beach—that intertidal zone between land and sea—where local and classical interpretations continue to wash up against each other. It seems the problems we face today are no less sombre, no less sensitive and no less ambivalent than they were decades or even centuries ago.3

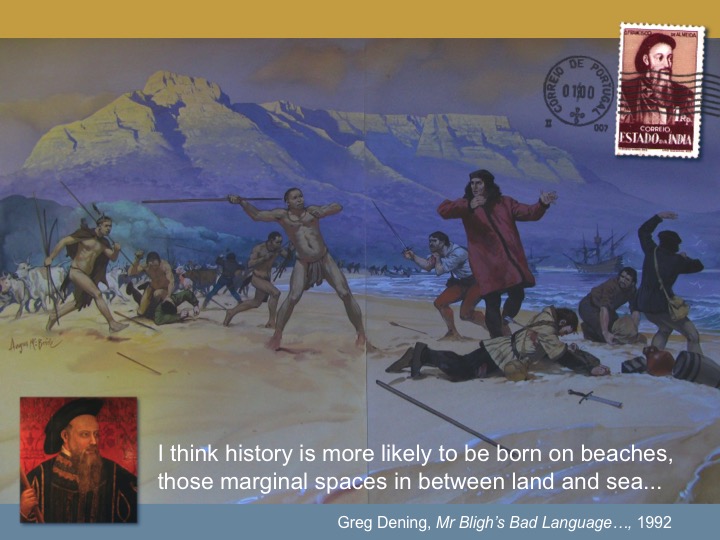

The untimely death of Dom Francisco d’Almeida remains an enigma to this day: was it an ambush, a mutiny or an assassination? Whatever the verdict, it has been called “one of the greatest tragedies in the history of Portugal” because the Portuguese failed to seize the Cape of Good Hope.4 For now, let Greg Dening’s statement suffice:

The untimely death of Dom Francisco d’Almeida remains an enigma to this day: was it an ambush, a mutiny or an assassination? Whatever the verdict, it has been called “one of the greatest tragedies in the history of Portugal” because the Portuguese failed to seize the Cape of Good Hope.4 For now, let Greg Dening’s statement suffice:

I think history is more likely to be born on beaches, those marginal spaces in between land and sea… where everything is relativised a little, turned around, where tradition is as much invented as handed down, where otherness is both a new discovery and a reflection of something old.5

Introduction

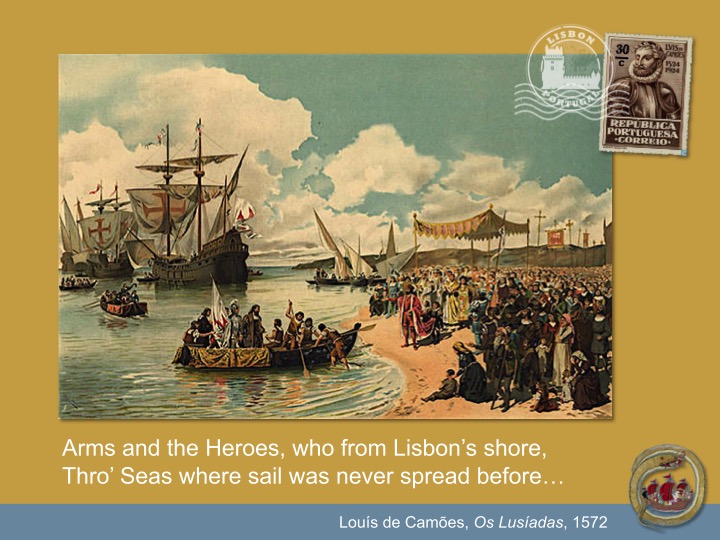

Let’s begin with the opening lines of Os Lusíadas.6 Epic poetry emboldens men of action and inspires a nation to greater deeds by way of good examples.

To this end, diverse heroes, dramatic battles and daring voyages became the leitmotifs of Camões’ national epic. He believed that great poetry, especially great epic poetry, should improve the moral marrow of a people and promote their sense of divine historical purpose. According to him, the gods favoured the plucky Portuguese.7

To this end, diverse heroes, dramatic battles and daring voyages became the leitmotifs of Camões’ national epic. He believed that great poetry, especially great epic poetry, should improve the moral marrow of a people and promote their sense of divine historical purpose. According to him, the gods favoured the plucky Portuguese.7

The idea that poetry, like drama, brings out the best in us wasn’t new, of course, but came from ancient Greece where Aristotle had argued that poetics expresses our highest human values and noblest aspirations.8 For the next two millennia poetry was seen as superior to history—and thus worthy of greater praise—because historical writing only tells us what we once were and not what we may yet become. In this regard Os Lusíadas became the founding myth for an emergent Portuguese nation.9

The idea that poetry, like drama, brings out the best in us wasn’t new, of course, but came from ancient Greece where Aristotle had argued that poetics expresses our highest human values and noblest aspirations.8 For the next two millennia poetry was seen as superior to history—and thus worthy of greater praise—because historical writing only tells us what we once were and not what we may yet become. In this regard Os Lusíadas became the founding myth for an emergent Portuguese nation.9

While the outbound journey to the Indies began and ended at opposite ends of the world, modern history was born where Native and Stranger, indigene and interloper first met. Camões, however, offers up more references to the glories of Greece and Rome than to all the splendours of Asia or Africa seen en route to the East.10

While the outbound journey to the Indies began and ended at opposite ends of the world, modern history was born where Native and Stranger, indigene and interloper first met. Camões, however, offers up more references to the glories of Greece and Rome than to all the splendours of Asia or Africa seen en route to the East.10

Evocations and Continuities

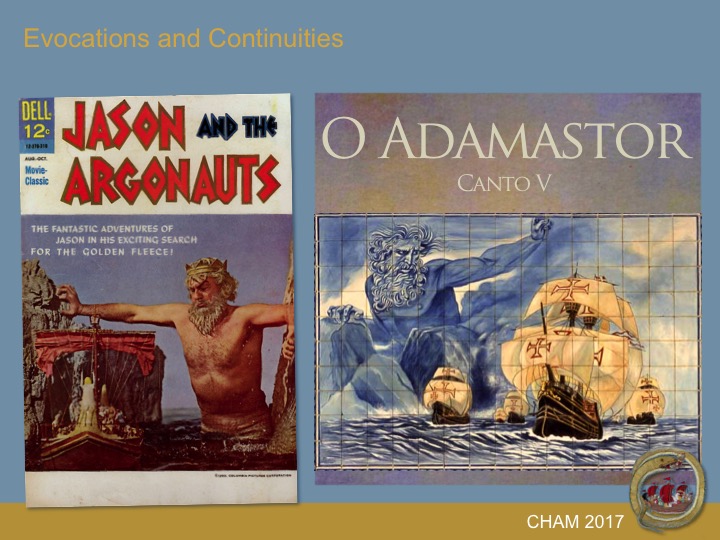

As per the brief for this panel, Evocations and Continuities, my paper traces several themes from Greco-Roman literature and their recurrence in an age of Portuguese overseas expansion. While these motifs are drawn from historical writings, most of my illustrations are taken from contemporary sources, giving this presentation an additional level of reflection not evident in my original text.

There are some clear historical parallels between the founding of an ancient Greek state and the rise of a Portuguese nation. Both Jason the Argonaut and Henry the Navigator were princes who sent their seafarers to the ends of the world and achieved what others thought impossible: they made the promise of return a reality.

There are some clear historical parallels between the founding of an ancient Greek state and the rise of a Portuguese nation. Both Jason the Argonaut and Henry the Navigator were princes who sent their seafarers to the ends of the world and achieved what others thought impossible: they made the promise of return a reality.

Moreover, Henry’s captains saw themselves as new-age argonauts and, once initiated into the Order of Christ (Ordem de Cristo), were enrolled as neo-Templar knights—as Knights of the Sea on a renewed crusade.11

World’s End

As a neo-Templar, Bartolomeu Dias was nicknamed “the Captain of the End”12 because he brought his men safely back from the farthest corner of the earth, from the southern hemisphere whose limit was still unknown.

Ironically, Dias had to return after his crew rebelled and refused to sail on, believing warmer waters signalled the precipitous End-of-the-Earth. Today we recognise this as the warm Agulhas current that sweeps down East Africa’s coast.

Ironically, Dias had to return after his crew rebelled and refused to sail on, believing warmer waters signalled the precipitous End-of-the-Earth. Today we recognise this as the warm Agulhas current that sweeps down East Africa’s coast.

We also know that sub-Saharan Africa was neither peripheral nor isolated but complexly bound to the Indian Ocean Rim and Atlantic trade routes, to the balance of power between Asia and Europe, and to age-old relationships between a mystical East and a rational West. Perhaps this explains why Africa, rather than Britain, was seen as the true home of the Grail.13

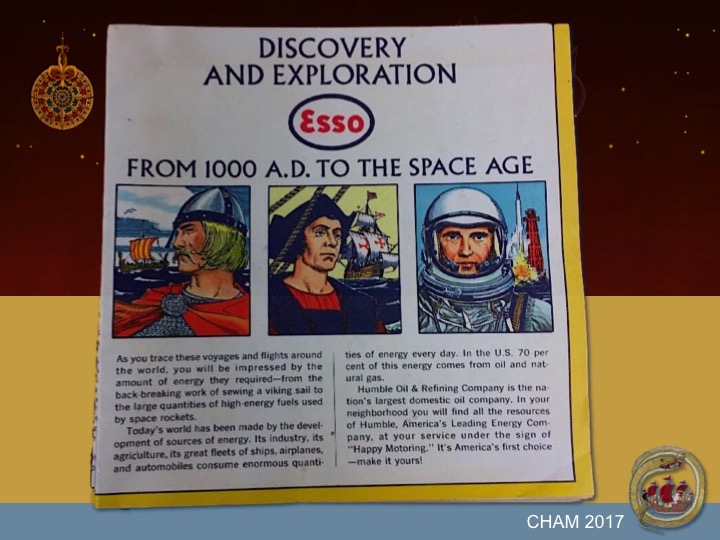

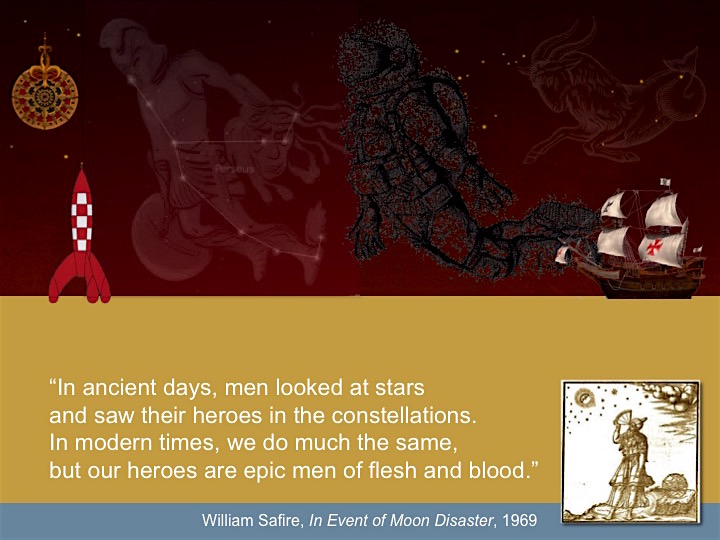

Another parallel can be drawn between the Age of Discoveries and the Space Age, between earth’s unexplored oceans and the oceans of space, between Columbus’ first epic voyage and NASA’s first moon landing when, as William Safire then put it, “Mother Earth dared send two of her sons into the unknown”.14 Safire was an American columnist and speechwriter who, two days before the historic Apollo landing, drafted a statement for President Nixon to read in the event of a disaster.

Another parallel can be drawn between the Age of Discoveries and the Space Age, between earth’s unexplored oceans and the oceans of space, between Columbus’ first epic voyage and NASA’s first moon landing when, as William Safire then put it, “Mother Earth dared send two of her sons into the unknown”.14 Safire was an American columnist and speechwriter who, two days before the historic Apollo landing, drafted a statement for President Nixon to read in the event of a disaster.

Safire’s statement was never broadcast but remains, to my mind, a most poignant comparison between the heroes of old and those of our own era:

Safire’s statement was never broadcast but remains, to my mind, a most poignant comparison between the heroes of old and those of our own era:

In ancient days, men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations. In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood.15

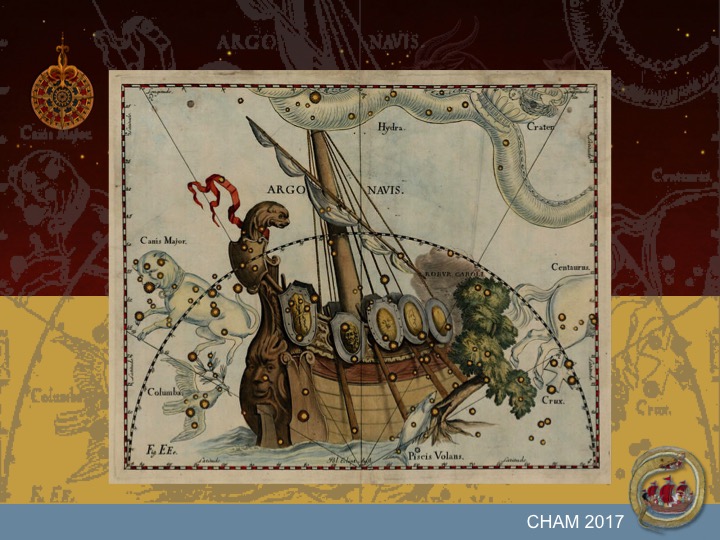

We now know that classical astrology was fixed between the time of the Argonauts and the Trojan War because, according to Sir Isaac Newton, the Argonauts were placed in our night sky and not the heroes of the Trojan War.16 While known as Argo Navis (Ship Argo), the constellation was found low on the southern Mediterranean sky.17 ‘The Ship’ was visible in spring and appeared to sail westward, skimming across the southern horizon, as if following the souls of the departed on their journey west.

We now know that classical astrology was fixed between the time of the Argonauts and the Trojan War because, according to Sir Isaac Newton, the Argonauts were placed in our night sky and not the heroes of the Trojan War.16 While known as Argo Navis (Ship Argo), the constellation was found low on the southern Mediterranean sky.17 ‘The Ship’ was visible in spring and appeared to sail westward, skimming across the southern horizon, as if following the souls of the departed on their journey west.

The link between argonaut and astronaut, seafarer and spaceman was reinforced by Safire’s recommendation that, once NASA broke off communication with the ill-fated crew, a clergyman should conduct the same procedure as a burial at sea, commending their souls to “the deepest of the deep”. The lunar ship would be their grave.

Underworld

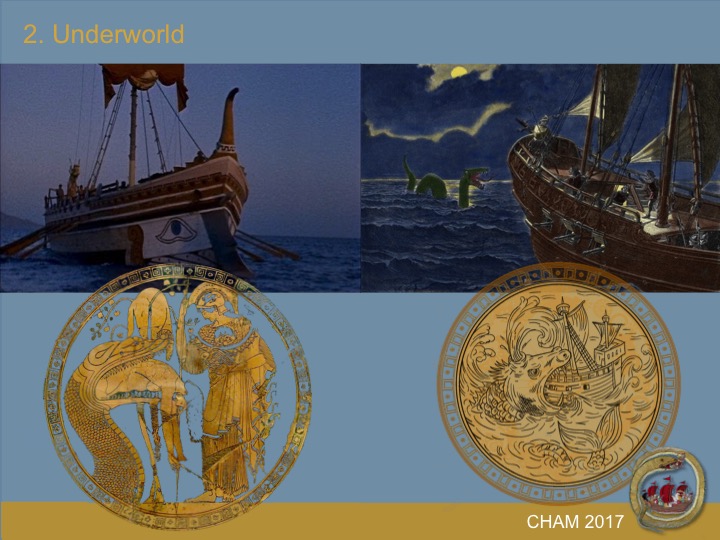

As a legacy of Antiquity, the warmer southern hemisphere was said to lead to the Underworld where the natural order was inverted and the heavens appeared to rotate in reverse, where sailors reported seeing the sun move across the sky on the “wrong” side of their boat.18

Like their predecessors, early Portuguese seafarers were trained to face terrible sea monsters and taught how to overcome their fear of the unknown. And since the voyage of the Argo symbolised a descent into the Underworld, a world of initiation, so did rounding the Cape of Good Hope, then revered as the Portal to the Indies.19 The Cape was seen as a sacred portal between the Atlantic and Indian oceans, a threshold between the Occident and the Orient, the familiar and the exotic, between Self and Other.20

Like their predecessors, early Portuguese seafarers were trained to face terrible sea monsters and taught how to overcome their fear of the unknown. And since the voyage of the Argo symbolised a descent into the Underworld, a world of initiation, so did rounding the Cape of Good Hope, then revered as the Portal to the Indies.19 The Cape was seen as a sacred portal between the Atlantic and Indian oceans, a threshold between the Occident and the Orient, the familiar and the exotic, between Self and Other.20

Paradise

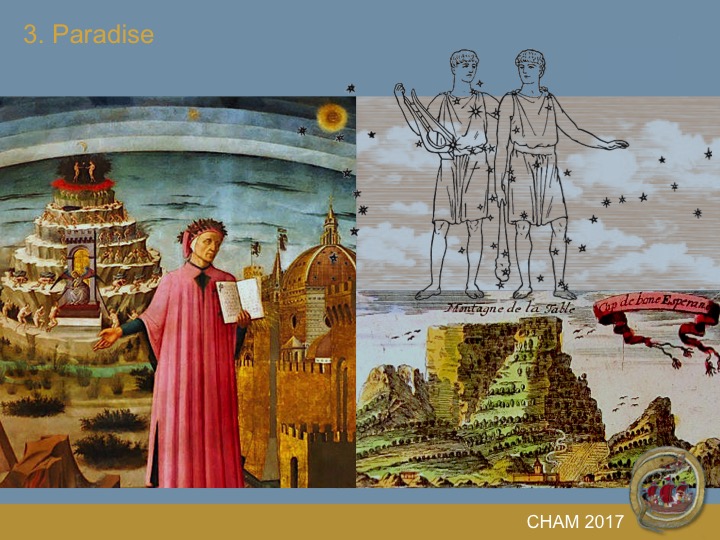

Dias’ passage around the foot of Africa was also seen as a rite of passage, west to east, from hardship to riches, from Tormentoso to Esperança, Torment to Hope, typecasting the Cape as a land of suffering and salvation, a place to purge the soul and attain enlightenment.21

There could thus be no Cape of Good Hope without a Cape of Storms, no Paradise without a Purgatory.22 It was Dante—that great admirer of Virgil—who invoked this when placing his Isle of Purgatory off to the South and his terrestrial Paradise on a flat-topped mountain rising above a watery transit.23

There could thus be no Cape of Good Hope without a Cape of Storms, no Paradise without a Purgatory.22 It was Dante—that great admirer of Virgil—who invoked this when placing his Isle of Purgatory off to the South and his terrestrial Paradise on a flat-topped mountain rising above a watery transit.23

Africa was long seen to possess two aspects, Gemini-like, with one side brutish, the other refined and fabulous. The notion of a continent divided between “savage” and “worthy” inhabitants can be traced back to the 8thC BCE when, during the late New Kingdom, Egypt’s ruling elite sought to distance itself from its African origins.24

The division between ‘superior’ and ‘inferior’ Africans laid the foundation for western racism and—via Homer, Herodotus, Pliny and Ptolemy—made its way into medieval art and literature. It became an obsession among Prince Henry and his successors, persisting into the 19thC under European explorers.

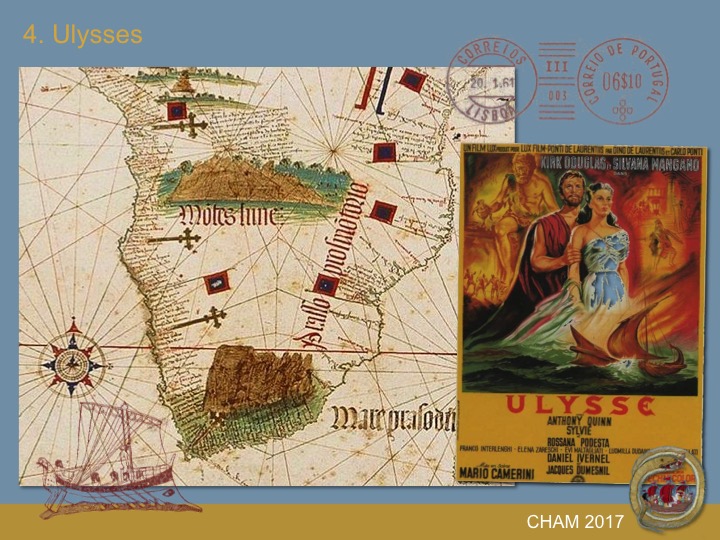

Ulysses

Virgil’s undaunted Ulysses, like Dias after him, sailed for several months until, suddenly, under the stars of the southern pole, he beheld “a mountain obscured by distance and of a height never seen before”.25

Table Mountain was thus imagined before it had been discovered, pre-dating Portugal’s first sighting by one hundred and fifty years. As reports filtered into Europe, Venetian mapmakers identified it as Dante’s visionary Mountain of the Sea and, soon enough, Table Mountain was likened to Paradise and Robben Island to Purgatory. It’s a bitter historical irony that the island was later used to isolate mutineering sailors, social outcasts and political prisoners.

Table Mountain was thus imagined before it had been discovered, pre-dating Portugal’s first sighting by one hundred and fifty years. As reports filtered into Europe, Venetian mapmakers identified it as Dante’s visionary Mountain of the Sea and, soon enough, Table Mountain was likened to Paradise and Robben Island to Purgatory. It’s a bitter historical irony that the island was later used to isolate mutineering sailors, social outcasts and political prisoners.

Cyclops

This Ulyssean imagery inspired Camões’ Adamastor which, as Guardian of the Portal, challenged Gama when he first entered Cape waters. The name Adamastor means “untamed” or “wild” and embodies all the hostile and vindictive character of the Cape.26 Adamastor protected the Cape of Storms from those who dared discover its secrets or seize Africa’s riches. He was turned to stone, like goddess Pyrene, protector of the pre-Christian sun-mysteries in Iberia.27 As Pyrene is to the Pyrenees, so Adamastor is to Table Mountain.

Camões uses the confrontation between Gama and Adamastor as a metaphor for the struggle between modern man and the classical gods. For him, as poet, man’s triumph over the gods symbolises the triumph of the Renaissance over the Medieval, humanism over dogmatism, faith over superstition; while the Gama-Adamastor confrontation represents the conflict between Europe and Africa, Empire and Colony, civilisation and barbarism.28

Camões uses the confrontation between Gama and Adamastor as a metaphor for the struggle between modern man and the classical gods. For him, as poet, man’s triumph over the gods symbolises the triumph of the Renaissance over the Medieval, humanism over dogmatism, faith over superstition; while the Gama-Adamastor confrontation represents the conflict between Europe and Africa, Empire and Colony, civilisation and barbarism.28

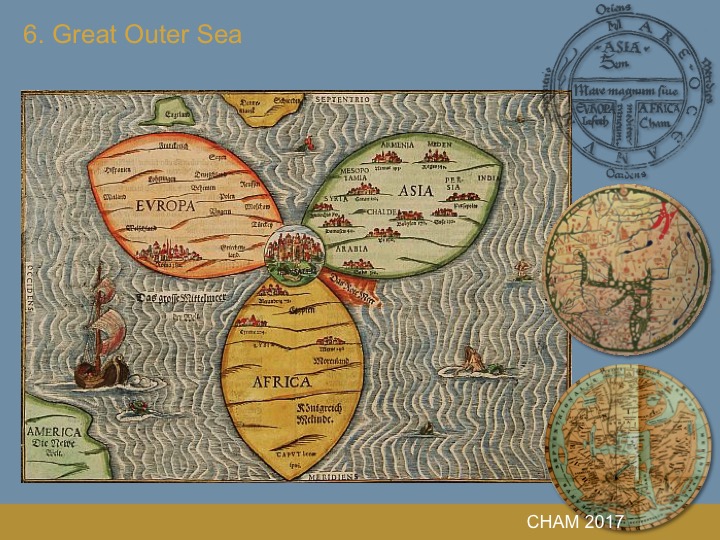

Great Outer Sea

Classical geographers believed a Great Outer Sea surrounded their world. The Greeks and Arabs saw this as a vast river, circular in form, encircling all Europe, Asia and Africa. From the geography taught by Aristotle, Nearchus of Crete, admiral of Alexander’s fleet, believed they had reached the Great Outer Sea in the East and that circumnavigation of the world was now possible.

Intrigued by the idea, Alexander dreamt of conquering Arabia Felix, thereby allowing his mariners to sail on to Egypt, a land he already controlled and where, unchallenged, his soldiers would dig a canal linking the Red Sea to the Nile—as Pharaoh Necho and Darius the Great had tried before—and so open up the Mediterranean. From Egypt he would go on to conquer Europe and Africa and, just as the Great Outer Sea bound the world, so his empire would unite all its people. The world would become a commonwealth of nations.

Intrigued by the idea, Alexander dreamt of conquering Arabia Felix, thereby allowing his mariners to sail on to Egypt, a land he already controlled and where, unchallenged, his soldiers would dig a canal linking the Red Sea to the Nile—as Pharaoh Necho and Darius the Great had tried before—and so open up the Mediterranean. From Egypt he would go on to conquer Europe and Africa and, just as the Great Outer Sea bound the world, so his empire would unite all its people. The world would become a commonwealth of nations.

But fate took another turn. Alexander died as Nearchus came to tell him that his new ships lay waiting at the Tigris-Euphrates estuary. And so the campaign was never launched. It was supposed to be a grand military, mercantile and scientific expedition: the circumnavigation of the world, east to west, via the Great Outer Sea.29

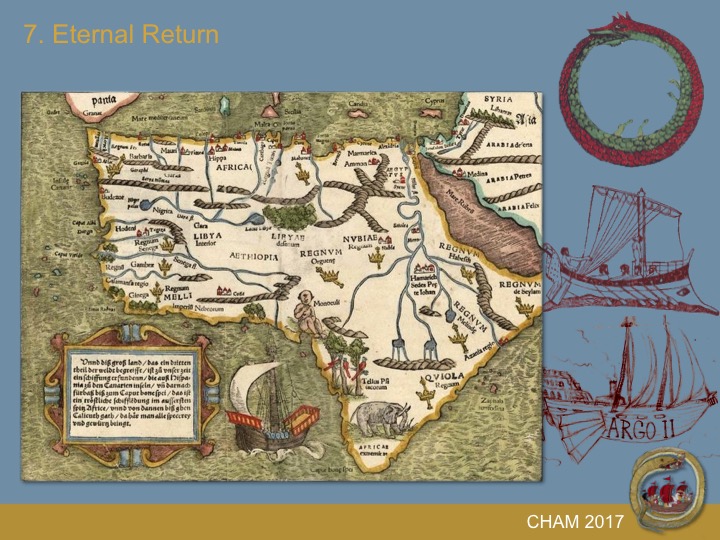

Eternal Return

Lastly, the Pythagoreans believed in the transmigration of the soul and that similar events occur over and over to the same people, the same families, and even to the same cities. Virgil, likewise, described how history repeats itself and “the great line of centuries begins anew as a second Argo carries its chosen heroes to another war, to another shore”.30 Similarly, numerous campaigns, from the siege of Moorish Granada (1492) to the conquest of Incan Chile (1541), have since been cast as repetitions of the Trojan War.

Here two Portuguese examples stand out. First, as Viceroy of Portuguese India, Francisco d’Almeida knew he would undertake the same sea voyage once planned by Nearchus, but in the opposite direction, west to east, and so fulfil Alexander’s dying dream of rounding Africa in order to expand an empire on new-found shores.31 Secondly, Almeida’s rival and successor in India, Captain-General Afonso de Albuquerque, arguably Portugal’s greatest conqueror, was given the notorious appellation “Caesar of the East”.32

Here two Portuguese examples stand out. First, as Viceroy of Portuguese India, Francisco d’Almeida knew he would undertake the same sea voyage once planned by Nearchus, but in the opposite direction, west to east, and so fulfil Alexander’s dying dream of rounding Africa in order to expand an empire on new-found shores.31 Secondly, Almeida’s rival and successor in India, Captain-General Afonso de Albuquerque, arguably Portugal’s greatest conqueror, was given the notorious appellation “Caesar of the East”.32

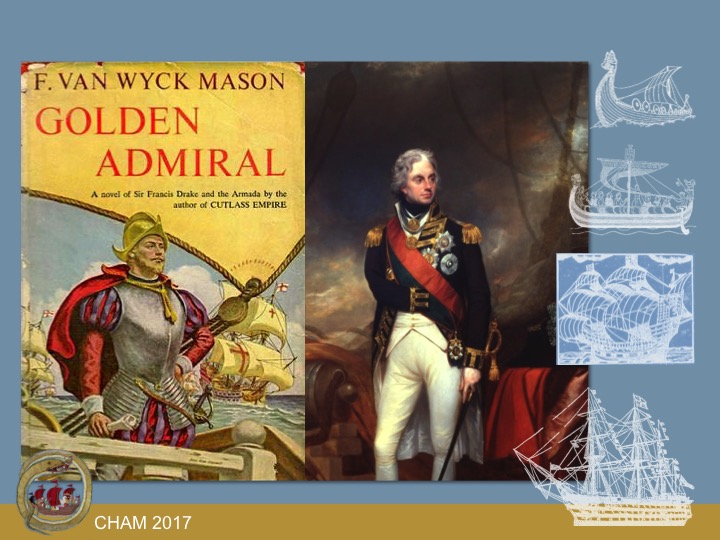

Following the Viking raids and Norman conquests of the 8th–11thC, the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588) and the Franco-Spanish Navies (1805) were viewed as repetitions of the same battle—namely England’s battle against invasion, first by Philip II of Spain, and then by Napoleon. In the English popular imagination, Sir Francis Drake and Lord Nelson were seen as one and the same hero, a guardian spirit who returns again and again to ensure their victory.33 The Edwardian poet Alfred Noyes adds that Drake was “first upon the deep that rolls to Trafalgar” 34 and, moreover, that local lore says the beat of Drake’s old drum has been heard through the ages—from Cromwell to Wellington, from Plymouth to Dunkirk. Perhaps this explains why the English keep reviving him.

Following the Viking raids and Norman conquests of the 8th–11thC, the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588) and the Franco-Spanish Navies (1805) were viewed as repetitions of the same battle—namely England’s battle against invasion, first by Philip II of Spain, and then by Napoleon. In the English popular imagination, Sir Francis Drake and Lord Nelson were seen as one and the same hero, a guardian spirit who returns again and again to ensure their victory.33 The Edwardian poet Alfred Noyes adds that Drake was “first upon the deep that rolls to Trafalgar” 34 and, moreover, that local lore says the beat of Drake’s old drum has been heard through the ages—from Cromwell to Wellington, from Plymouth to Dunkirk. Perhaps this explains why the English keep reviving him.

From a Pythagorean perspective, people ordinarily return to the same group but, from time to time, are reborn as allies and opponents, friends or rivals, in order to resolve conflictual relationships between families, cities and states. This implies that national heroes—including Drake and Nelson—do not fight for the same side each time but have “coursed through history like a wave through the ocean toward some as yet unknown shore”.35

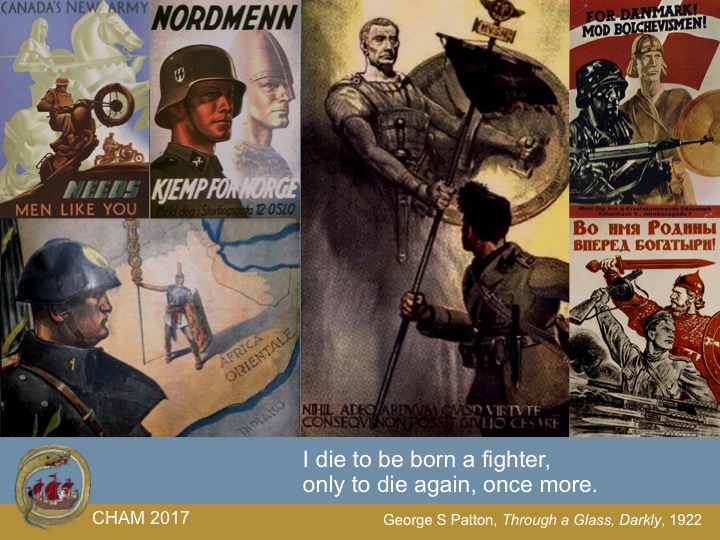

While comparisons between men-at-arms may be evocative, even metaphoric, they tend to remain speculative because it is not alone history that repeats itself but we who do. We return to fight another day or, as General Patton declared in ‘Through a Glass, Darkly’:

While comparisons between men-at-arms may be evocative, even metaphoric, they tend to remain speculative because it is not alone history that repeats itself but we who do. We return to fight another day or, as General Patton declared in ‘Through a Glass, Darkly’:

So forever in the future,

Shall I battle as of yore,

Dying to be born a fighter,

But to die again, once more.36

Although a staunch fatalist, Patton blended his belief in reincarnation with his knowledge of military history and alluded to several past lives in which he’d fought and died. He claimed to remember being a citizen-soldier in the Greco-Persian Wars (499–449BCE), a soldier for Alexander at the siege of Tyre (332BCE), a brother-in-arms of Hannibal during the Second Punic War (218–201BCE), a legionary in Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars (58–50BCE), a Norse Viking, an English knight during the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) and, lastly, as a grand officer in the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). While no marine, Patton still found himself on several far-flung shores several times.

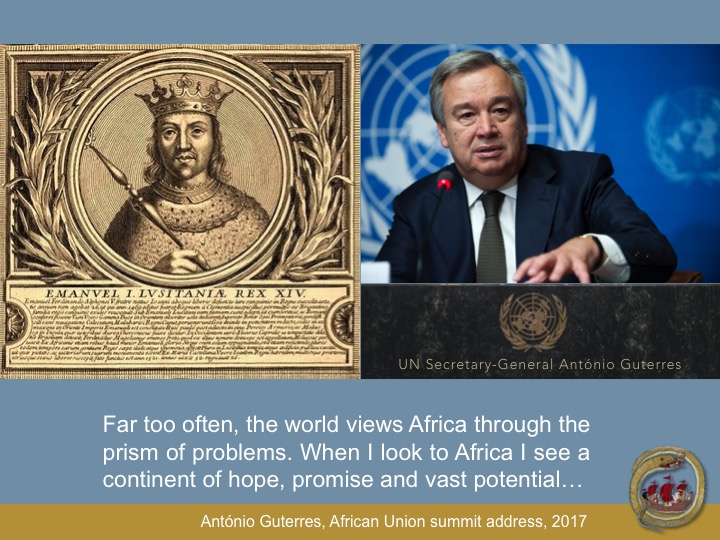

Finally, there’s always that last slide which should be removed from a presentation since it may provoke or push a point too far. Perhaps this is that one. The citation, “When I look to Africa I see a continent of hope, promise and vast potential”,37 could easily have been said by king Manuel, not because both men are Portuguese or because they hold, held, the balance of power/order in their respective worlds, but because of what has been suggested regarding the current United Nations SG António Guterres:

Finally, there’s always that last slide which should be removed from a presentation since it may provoke or push a point too far. Perhaps this is that one. The citation, “When I look to Africa I see a continent of hope, promise and vast potential”,37 could easily have been said by king Manuel, not because both men are Portuguese or because they hold, held, the balance of power/order in their respective worlds, but because of what has been suggested regarding the current United Nations SG António Guterres:

He is the reincarnation of Manuel I, nicknamed “the Fortunate” because he was lucky to have become king of Portugal. Let’s hope luck will be on his side in this life for the sake of world peace.38

Conclusion

In conclusion, the repetition of classical motifs is widespread and occurs across all cultures, all ages, all genders, and is as old as storytelling itself. In turn, the legend of the Argo is itself an evocation of far older myths that reach into the mists of time. Their continuity is surely proof that we choose to tell and retell, live and relive, our past in ever new ways. To do so may embolden us, enlighten us, entertain us, or simply remind us of whom we once were.

I thank you for your patience, and thank the CHAM conference organisers for this opportunity, albeit thirty years since submitting my first essay to colleagues at the University of Lisbon.

I thank you for your patience, and thank the CHAM conference organisers for this opportunity, albeit thirty years since submitting my first essay to colleagues at the University of Lisbon.

Nicolaas Vergunst

As usual I think you’ve done it splendidly.

Really impressive.

Thanks for sharing it with me.

All good wishes for the conference.

Ik heb je lezing nog eens goed doorgenomen en ben diep onder de indruk. To the point, very good quotes, en een belangrijke doorlopende lijn in de gedachte en begripsvorming! Krachtig, bescheiden en innoverend. Wat heb je een duidelijke taal en een prachtig gevoel voor de combinatie van tekst en beeld. Compliment!