This paper was written for the Exploration and Memory conference at the National Maritime Museum (NMM) in London, 13–15 September 2018, and draws on recent insights and responses to Knot of Stone.1

This paper was written for the Exploration and Memory conference at the National Maritime Museum (NMM) in London, 13–15 September 2018, and draws on recent insights and responses to Knot of Stone.1

Good morning, I was born in South Africa of post-war Dutch immigrants and wish to acknowledge the indigenous people of Camissa, now Cape Town, and their custodianship of the land. I also wish to pay tribute to the victims in my research, both indigene and interloper, whose graves are lost and forgotten.

My paper examines the first recorded massacre and earliest known murder in South African history, namely the 1510 battle of Goringhaiqua and the death of Francisco d’Almeida, 1st Viceroy of Portugal’s territorial claims in India.

By highlighting several discrepancies in the records, I hope to provide a more layered and nuanced understanding of what happened that fateful morning when the tide ran high in Table Bay.

From a Portuguese perspective, the southern tip of Africa was revered as a Portal to the Indies and as a threshold to their vast overseas empire which stretched from the Cape of Good Hope to Cape Comorin.2 By the 16thC it was the largest empire in the world, albeit mostly sea. At this time there was no fort or settlement at the Cape.

From a Portuguese perspective, the southern tip of Africa was revered as a Portal to the Indies and as a threshold to their vast overseas empire which stretched from the Cape of Good Hope to Cape Comorin.2 By the 16thC it was the largest empire in the world, albeit mostly sea. At this time there was no fort or settlement at the Cape.

On the other hand, the Goringhaiqua were a sub-group of Khoena pastoralists living on the lower slopes of Table Mountain (below the University of Cape Town today) and called their home Camissa, meaning Place of Sweet Waters. Here, on Friday 1 March, the Viceroy was led ashore, attacked, slain and hurriedly buried in a shallow, sand-covered grave. His death remains a mystery to this day. Was it the fulfillment of a prophecy or an act of poetic justice? Was it an ambush, a mutiny or an assassination?

On the other hand, the Goringhaiqua were a sub-group of Khoena pastoralists living on the lower slopes of Table Mountain (below the University of Cape Town today) and called their home Camissa, meaning Place of Sweet Waters. Here, on Friday 1 March, the Viceroy was led ashore, attacked, slain and hurriedly buried in a shallow, sand-covered grave. His death remains a mystery to this day. Was it the fulfillment of a prophecy or an act of poetic justice? Was it an ambush, a mutiny or an assassination?

According to the historical records, the returning Viceroy reached the Cape of Good Hope around 20 February and came ashore (probably near today’s V&A Waterfront) to collect clean water and dry wood. He and his men spent the following 10 days replenishing their supplies, repairing the boats, and befriending a few intrepid herders who had come down to the beach. Both parties were curious and tentatively traded trinkets for treats. However, once on familiar footing, the bartering escalated as the Khoena desired metal items and the Portuguese fresh meat—goods which neither side wished to part with.

However, the pre-colonial Cape is often depicted as a pastoral paradise, a time and place without strife, conflict or discrimination—and where no one lied or stole.3

This engraving of the Cape of Good Hope dates from 1669,4 one hundred and fifty years after the death of Almeida, and is based on sketches made by a VOC soldier-adventurer, Albrecht Herport, who had visited the Cape a decade earlier. While most pictures were made by engravers who never visited the Cape, this view of Table Mountain is remarkably accurate as Herport sketched it himself “naert leven” (from life). The rhinoceros, however, was copied after Albrecht Dürer’s famous Asian rhino woodcut of a hundred and fifty years earlier, 1515. While the Khoena wear the traditional sheepskin cloak (kaross) and rolled leather thongs (riems) around their legs, their bodies are composed like figures in a Greek pediment. Here fact and fantasy combine in a single work to create an ‘Arcadian Africa’. Likewise, written accounts tried to combine the same elements into a seamless historical record.5

This engraving of the Cape of Good Hope dates from 1669,4 one hundred and fifty years after the death of Almeida, and is based on sketches made by a VOC soldier-adventurer, Albrecht Herport, who had visited the Cape a decade earlier. While most pictures were made by engravers who never visited the Cape, this view of Table Mountain is remarkably accurate as Herport sketched it himself “naert leven” (from life). The rhinoceros, however, was copied after Albrecht Dürer’s famous Asian rhino woodcut of a hundred and fifty years earlier, 1515. While the Khoena wear the traditional sheepskin cloak (kaross) and rolled leather thongs (riems) around their legs, their bodies are composed like figures in a Greek pediment. Here fact and fantasy combine in a single work to create an ‘Arcadian Africa’. Likewise, written accounts tried to combine the same elements into a seamless historical record.5

After a week, Almeida yielded to requests that a few of his men visit a nearby village to see if they could obtain cattle or sheep. It was here that a quarrel began, some say over pilfered knifes, others over stolen livestock, resulting in a brawl which ended with the sea rogues running back with a bloodied nose and broken teeth. Once aboard the flagship, the humiliated fidalgoes asked Almeida to return and punish the villagers. Reluctantly he agreed, and early the next morning, before sunrise, he set ashore with an ad hoc party of 150 lightly-armed men. En route some belligerent servants (including those involved in the escapade the day before) ran ahead to raid the village where—as far as I know—the first white man was killed. An accident, they said, as he was stabbed by an over-zealous compatriot in the chaos.

After a week, Almeida yielded to requests that a few of his men visit a nearby village to see if they could obtain cattle or sheep. It was here that a quarrel began, some say over pilfered knifes, others over stolen livestock, resulting in a brawl which ended with the sea rogues running back with a bloodied nose and broken teeth. Once aboard the flagship, the humiliated fidalgoes asked Almeida to return and punish the villagers. Reluctantly he agreed, and early the next morning, before sunrise, he set ashore with an ad hoc party of 150 lightly-armed men. En route some belligerent servants (including those involved in the escapade the day before) ran ahead to raid the village where—as far as I know—the first white man was killed. An accident, they said, as he was stabbed by an over-zealous compatriot in the chaos.

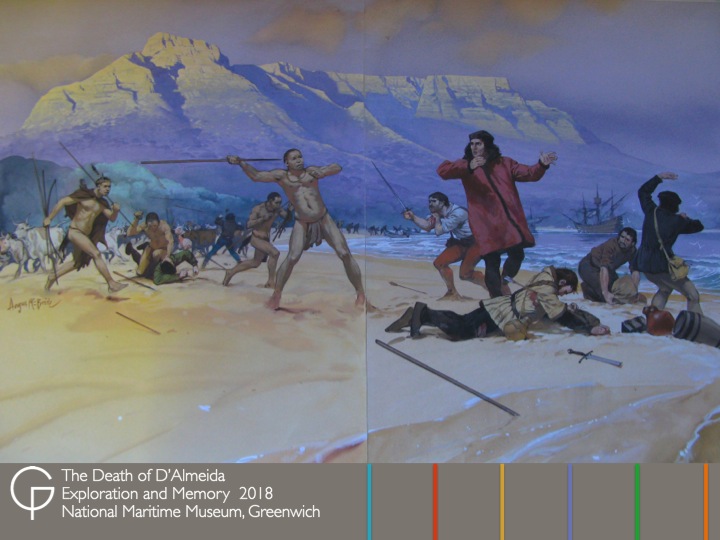

When news of this fiasco reached Almeida, still on his way, he had the march called off. But is was too late as the bellicose fidalgoes came running by with what they had managed to steal or kidnap. Provoked by this aggressive invasion, the Khoena drove their cattle against the Portuguese and forced them back to the beach. Here, abandoned by the main body of his men, Almeida was struck and sank to his knees. He and sixty-odd compatriots died where they fell. Local losses were not recorded.

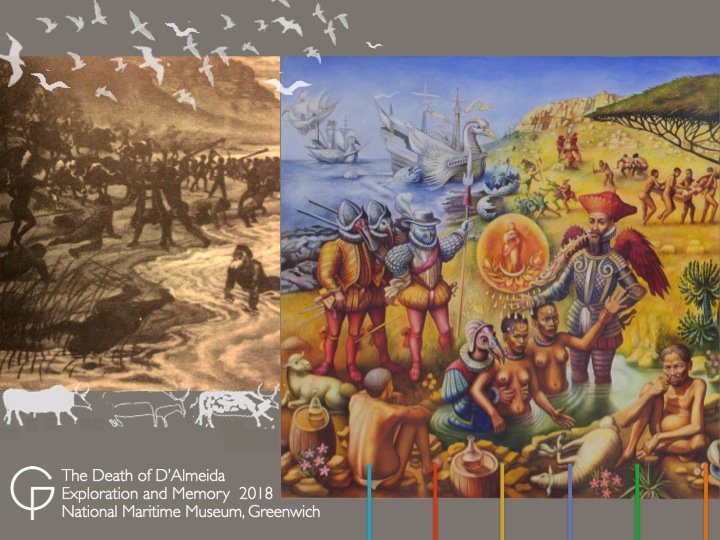

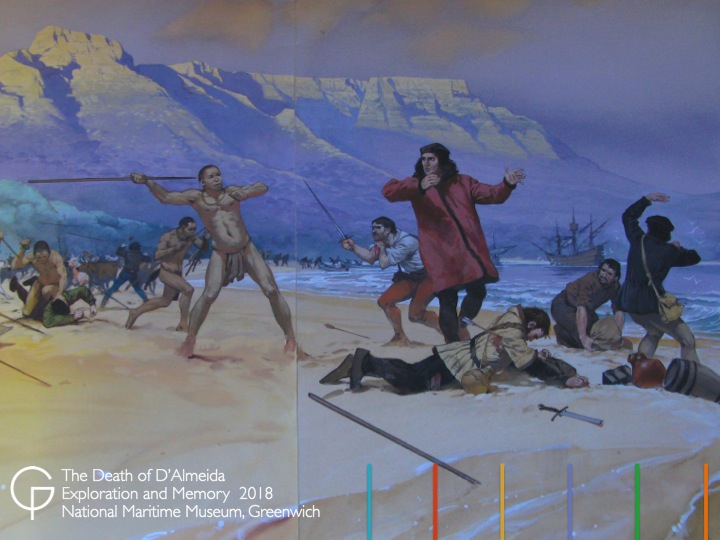

Although the actual location has been disputed,6, 7, 8 the painting above captures—at least to my mind—the scene with uncanny accuracy: a long beach hemmed in by low dunes, a river mouth and the rising tide. This gouache is by the renown historical illustrator Angus McBride and belongs to the Castle Military Museum in Cape Town.9 There is one other depiction of the masscare, an engraving, published in Holland two-and-a-half centuries earlier. We shall examine this in a moment. Let us first look at a slavish copy of the painting above.

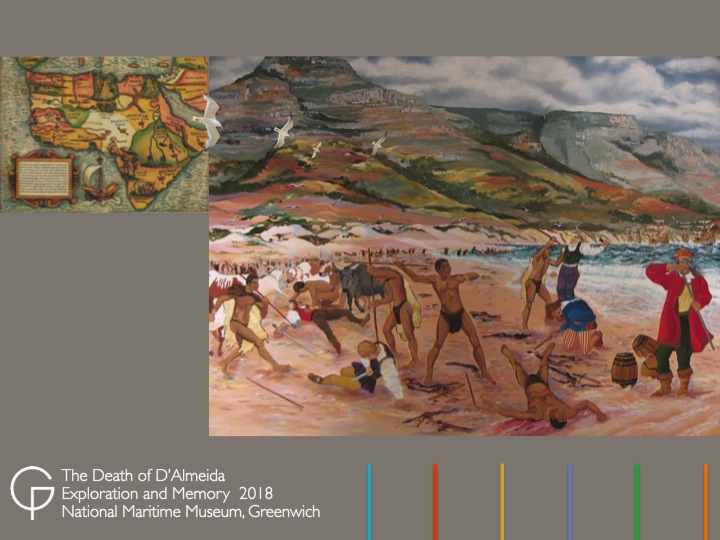

Like the copying of African maps, the Almeida-Khoena story has been told and retold, in text and image, reproducing inconsistencies and contradictions until they appear as fact. For example, this dramatic but amateurish copy shows ill-equipped soldiers and seamen supposedly on a punitive expedition. Does this point to over-confidence or arrogance on the part of the veteran officers? Or to the tactical ingenuity and skill of the warrior herdsmen? Local activists conclude that the Portuguese were “out-generalled” by the Khoena.10, 11, 12

Like the copying of African maps, the Almeida-Khoena story has been told and retold, in text and image, reproducing inconsistencies and contradictions until they appear as fact. For example, this dramatic but amateurish copy shows ill-equipped soldiers and seamen supposedly on a punitive expedition. Does this point to over-confidence or arrogance on the part of the veteran officers? Or to the tactical ingenuity and skill of the warrior herdsmen? Local activists conclude that the Portuguese were “out-generalled” by the Khoena.10, 11, 12

But let’s return to our story. Those who survived the attack fled to the safety of their boats in the bay. The fleeing body of men can be seen in the background. Their defeat and withdrawal from the Cape, never to return by order of king Manuel I, would later be described as one of the greatest tragedies in Portuguese history.13

It appears that Almeida suspected the bellicose behaviour of his men and that they had been used by antagonistic officers to lure him ashore where they planned to have him killed, either by the herders or by those men already turned against him, whichever proved more opportune. His suspicions proved accurate when his assassins ritually executed him after the battle. It was done that same day, once the herders had withdrawn from the beach, and a party sent ashore to bury the dead.

It appears that Almeida suspected the bellicose behaviour of his men and that they had been used by antagonistic officers to lure him ashore where they planned to have him killed, either by the herders or by those men already turned against him, whichever proved more opportune. His suspicions proved accurate when his assassins ritually executed him after the battle. It was done that same day, once the herders had withdrawn from the beach, and a party sent ashore to bury the dead.

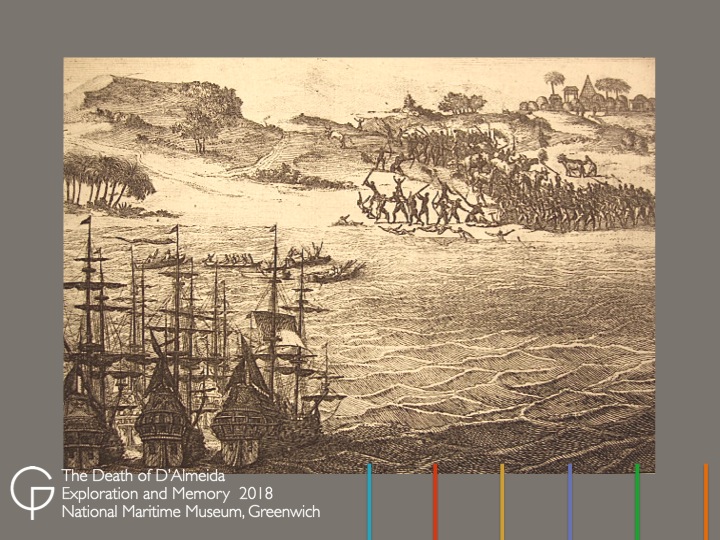

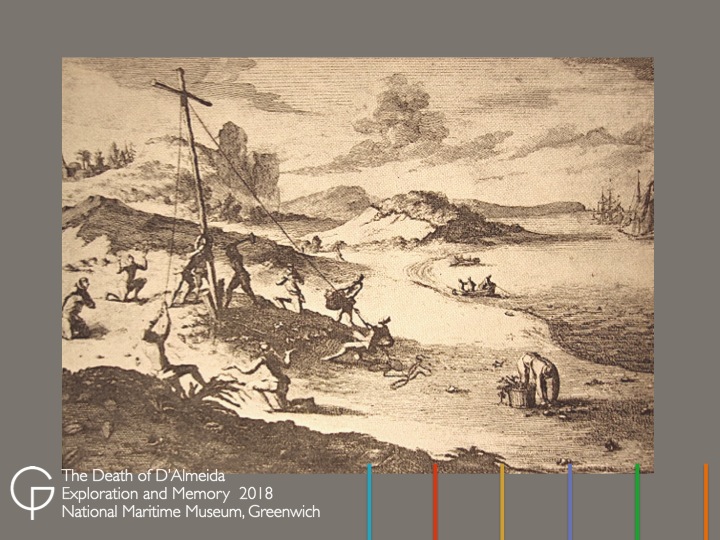

Here we see the earliest known illustration of the Almeida-Khoena massacre, engraved two centuries after the event, in 1707. It was published by Pieter van der Aa, a renown cartographer and printer in Holland, for his collection of notable land and sea travels to the East.14 Note that the five ships are Dutch galleons and not the three Portuguese carracks that we should expect to see. The fanciful huts, palms and pyramid also reveal more about the artist (who incidentally never saw the Cape) than they do about the event itself. Despite this, the two streams flowing from behind a flat-topped mountain seem to suggest a site near Table Mountain and the Liesbeeck-Salt River estuary. The estuary has since been canalized. We shall return to the actual site in our last slides.

For such a great tragedy, we may ask, why were so few images made—only two or three in five hundred years—and why did it receive such sporadic attention? All the more remarkable is the lack of protest or critique among indigenous voices, especially in the Western Cape, where the event was all but forgotten for centuries. From a local perspective, opposition to colonial readings of the event only entered the public domain when self-declared descendants started using it in post-apartheid identity politcs.

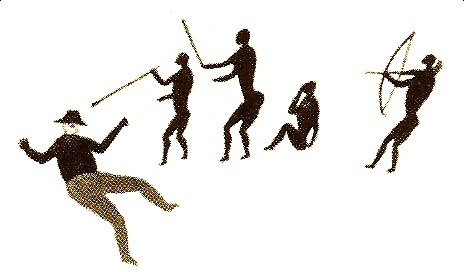

The Khoena kept large herds of war-trained cattle which, when driven together, formed a formidable battering ram and protective shield. This can be seen in the above painting from Brakfontein, Eastern Cape, showing a Khoisan hunting scene. Early European travel writers observed how the Khoena darted in and out of their herds, whistling instructions as they drove their long-horned beasts into a stampede. Unable to withstand the onslaught, Almeida’s party fell back to the beach where, once hemmed in between the dunes and rising tide, they found themselves overwhelmed by the herdsmen. Here they met their end under a hail of slingshot-stones and fire-hardened spears. Some say he was struck behind the knee by a stone, others that an assegai pierced his throat.

The Khoena kept large herds of war-trained cattle which, when driven together, formed a formidable battering ram and protective shield. This can be seen in the above painting from Brakfontein, Eastern Cape, showing a Khoisan hunting scene. Early European travel writers observed how the Khoena darted in and out of their herds, whistling instructions as they drove their long-horned beasts into a stampede. Unable to withstand the onslaught, Almeida’s party fell back to the beach where, once hemmed in between the dunes and rising tide, they found themselves overwhelmed by the herdsmen. Here they met their end under a hail of slingshot-stones and fire-hardened spears. Some say he was struck behind the knee by a stone, others that an assegai pierced his throat.

The earliest extant records were made by court chroniclers about half a century after the event,15, 16 long after any eye witnesses could question the records. As far as we know, no one challenged the account, at least not officially, nor did any one ask if there had been foul play; such as mutiny or assassination? Remarkably, the royal account remained uncontested for five hundred years; that is, until the event’s quincentenary in 2010.

Since then a new generation of voices has made much of their Khoena victory—their first and last against a major colonial power—and see the killing of Almeida as their finest hour, giving them pride of place in modern history.17 Their discourse serves an ulterior motive, promoting indigenous memory, cultural identities and land restitution claims.

Since then a new generation of voices has made much of their Khoena victory—their first and last against a major colonial power—and see the killing of Almeida as their finest hour, giving them pride of place in modern history.17 Their discourse serves an ulterior motive, promoting indigenous memory, cultural identities and land restitution claims.

Ironically, as admiral of the Portuguese fleet in the Bahr-al-Hind, the so-called Indian Sea, Almeida sailed in search of a soft blend of old religions. As viceroy he governed a region of the world where the oldest blend of Christianity still preserved elements of Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism and Islam. Here a dialogue between the Abrahamic and the Dharmic was still possible and, to this end, he allegedly received a “secret commission” to reopen esoteric exchange between East and West, between an old world and the new.18 This would eventually cost him his life.

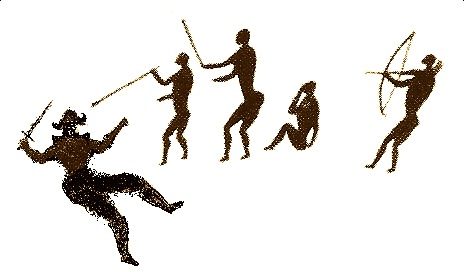

The image on the right was produced for the publication of Knot of Stone and does not exist in reality. It derives from a scene depicting a Dutch trekboer being attacked by hunter-gatherers, originally copied by George Stow in the Wittenberg region, Eastern Cape, mid-19thC.19

On the left is Stow’s copy, and to the right my copy of the copy.

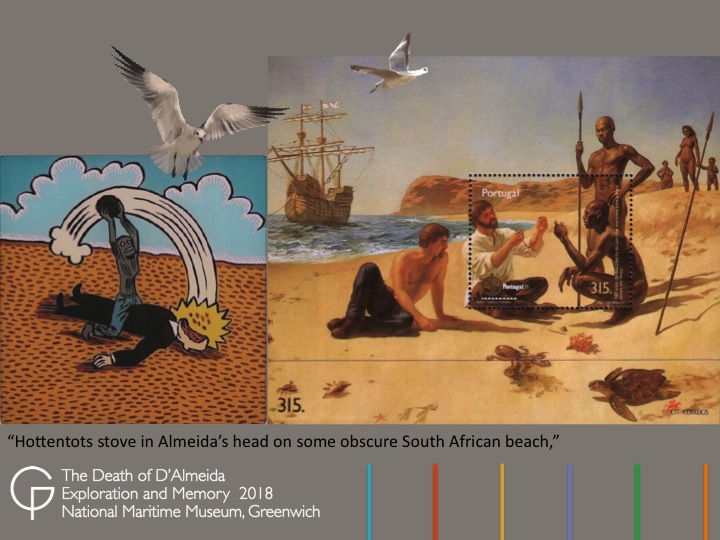

Mention of Almeida’s defeat also tend to be brief, and I quote, “Hottentots stove in Almeida’s head on some obscure South African beach”.20 Moreover, the recent renaming of the event as the Battle of Goringhaiqua shifts the focus from interloper to indigene, from defeat to victory. Today the event symbolises the first act of black anti-colonial resistance in South Africa and the first victory in the country’s long anti-colonial struggle. In his 1999 farewell speech to retiring president Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki evoked the defeat of Almeida saying “the victory … has lit our skies for ever”.21

While first encounters tend to be idealised, modern history was born on our beaches—that no man’s land between the dunes and the sea—where the natives first met the interlopers.22 This “intertidal zone of history” is where all things get washed up, where interrelations are intricate and nothing is permanent.

Today there is no intertidal space where Africa’s past and Europe’s history do not intersect, no beach below Table Mountain where the footprints of both native and interloper have not overlapped, and no reconstruction of Almeida’s murder from which either party can escape. It is one event that binds us together.

Significantly, both classical/defeat and local/victory authors follow the same storyline and core structure. Even when emphasizing, omitting or adding details, each version remains true to the received account. Versions come and go, but the account itself has not changed. For instance, Almeida is seen as a victim of fate and predestination23 and, simultaneously, as a treacherous tyrant.24 Similarly, Almeida’s men are noted for their valour25 and for having fled like cowards.26 Such anomalies are the result of political biases rather than of historical inaccuracies.27 They were both friend and foe.

Significantly, both classical/defeat and local/victory authors follow the same storyline and core structure. Even when emphasizing, omitting or adding details, each version remains true to the received account. Versions come and go, but the account itself has not changed. For instance, Almeida is seen as a victim of fate and predestination23 and, simultaneously, as a treacherous tyrant.24 Similarly, Almeida’s men are noted for their valour25 and for having fled like cowards.26 Such anomalies are the result of political biases rather than of historical inaccuracies.27 They were both friend and foe.

According to the records the victorious herders stripped Almeida’s body after battle. And yet no single artefact has been found: no helmet, no sword, no buckle, no button. Not one trophy or souvenir. Nor has any oral tradition been passed on.

According to the records the victorious herders stripped Almeida’s body after battle. And yet no single artefact has been found: no helmet, no sword, no buckle, no button. Not one trophy or souvenir. Nor has any oral tradition been passed on.

We are thus left to imagine how the sea rogues were perceived: Were they seen as the Strange Ones from across the great water, from the nesting place of the sun, concealed as white-winged birds? Did they swim to shore like fish with flashing fins and, once transformed under reptilian scales, spit fire? Did they fall upon their prey with the claws of an animal? Were they bird, fish, reptile and animal, four-in-one, unlike anything ever seen before? Were they the abeLungu?28

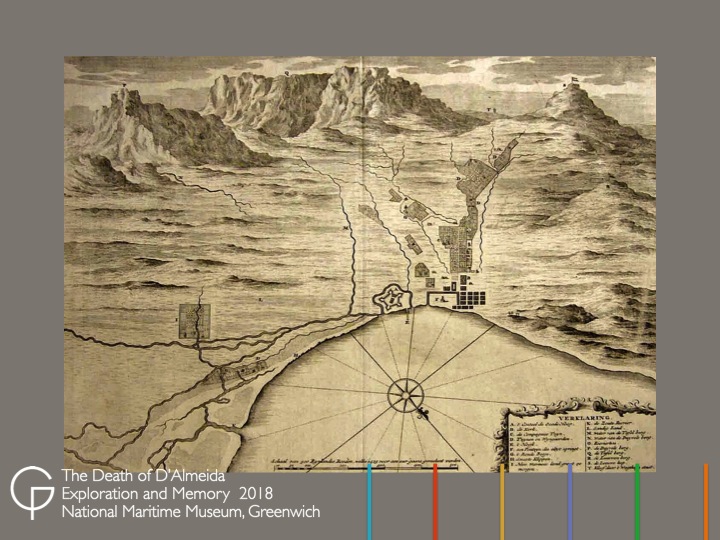

The first depictions of Table Valley date from the century after the massacre and show a seemingly secure and permanent settlement nestled between the mountain and the sea. The concentration of detail, however, wanes as one travels further afield, away from the castle—then the seat of power and authority—toward the interior at the extreme lower left. Here the wetland marshes around the Salt, Liesbeeck and Black rivers are shown. This is also where Almeida was killed.

The first depictions of Table Valley date from the century after the massacre and show a seemingly secure and permanent settlement nestled between the mountain and the sea. The concentration of detail, however, wanes as one travels further afield, away from the castle—then the seat of power and authority—toward the interior at the extreme lower left. Here the wetland marshes around the Salt, Liesbeeck and Black rivers are shown. This is also where Almeida was killed.

Shown here is the Dutch Caabse Vlek nestled between Table Mountain and Table Bay by François Valentijn, 1726.29 The map avoids all reference to the Khoena or San and, like so many other documents of this time, presents the interior as virgin territory waiting to be discovered, surveyed and occupied.

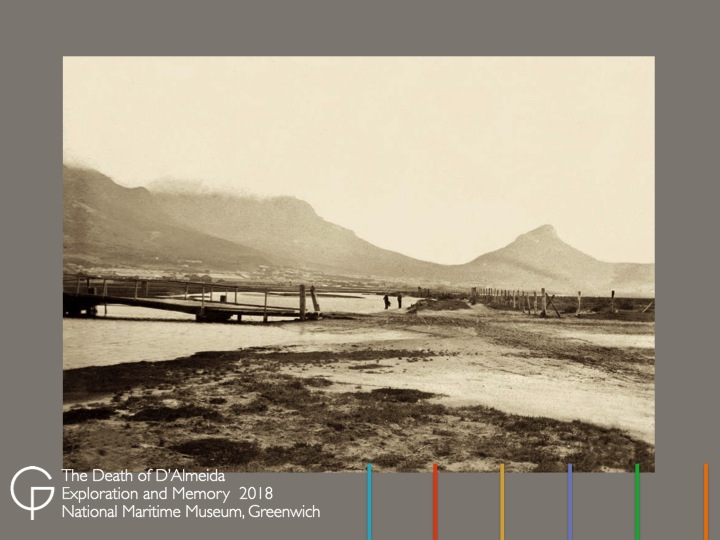

The old Salt River estuary looking towards Woodstock Beach, with a cloud covered Table Mountain in the background, c.1905.

The old Salt River estuary looking towards Woodstock Beach, with a cloud covered Table Mountain in the background, c.1905.

However, due to natural silting, land reclamation and river canalisation the beach lies buried underground today and the sea some two kilometres away. Despite this, the site has allegedly been identified by a local dowser.30 The white circle pin-points the spot.

However, due to natural silting, land reclamation and river canalisation the beach lies buried underground today and the sea some two kilometres away. Despite this, the site has allegedly been identified by a local dowser.30 The white circle pin-points the spot.

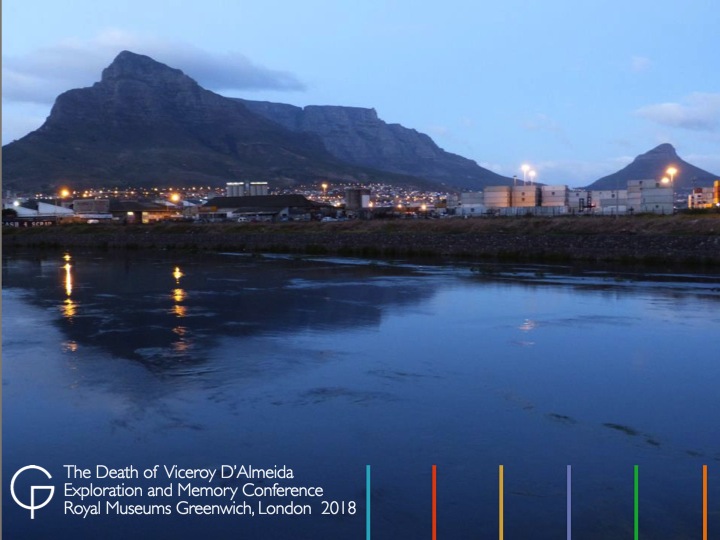

The identified site is where the Liesbeeck-Salt River once met the sea. The container terminal across the canal marks the alleged battle site. I took this photograph at dawn on Friday 1 March 2013 to show what light conditions may have been like five centuries ago. I now live abroad, but return each year to visit the site.

The identified site is where the Liesbeeck-Salt River once met the sea. The container terminal across the canal marks the alleged battle site. I took this photograph at dawn on Friday 1 March 2013 to show what light conditions may have been like five centuries ago. I now live abroad, but return each year to visit the site.

African Sacred Ibises scavenge over what may be the site of South Africa’s first battlefield. There is no memorial here, nor anywhere else in South Africa or Portugal, that acknowledges both the victims and the descendants of the Almeida/Khoena massacre. It is a windswept wasteland of derelict sheds, scrap metal yards and refuse dumps. A no man’s land hemmed in between a busy road and a disused shunting yard.31

African Sacred Ibises scavenge over what may be the site of South Africa’s first battlefield. There is no memorial here, nor anywhere else in South Africa or Portugal, that acknowledges both the victims and the descendants of the Almeida/Khoena massacre. It is a windswept wasteland of derelict sheds, scrap metal yards and refuse dumps. A no man’s land hemmed in between a busy road and a disused shunting yard.31

As a historical footnote, two years after the massacre, in 1512, the master of Almeida’s ship took a relative ashore to show him the grave. As the site could not be found, a wooden cross and stone cairn were erected to mark the spot, making this the first war memorial in South Africa. Both cross and cairn have long since disappeared, probably destroyed or buried. This engraving, also by Van der Aa, was all but forgotten until Cape Archivist Victor de Kock correctly identified it in 1952.32

As a historical footnote, two years after the massacre, in 1512, the master of Almeida’s ship took a relative ashore to show him the grave. As the site could not be found, a wooden cross and stone cairn were erected to mark the spot, making this the first war memorial in South Africa. Both cross and cairn have long since disappeared, probably destroyed or buried. This engraving, also by Van der Aa, was all but forgotten until Cape Archivist Victor de Kock correctly identified it in 1952.32

Finally, to my mind, the most important insights in recent decades have come from two independent sources; an Austrian-German philosopher and a South African psychiatrist. Walter Johannes Stein was clairvoyant and during a “retrospective vision” on 27 June 1924 relived the last fateful hours of Almeida.33 Laurence Oliver, who may be described as a white sangoma (a traditional healer empowered by the ancestors), received an unexpected clairaudient message in 2003 in which Almeida’s fated end is told. Both point to an assassination in which the Viceroy was ritually executed by his own men.

Finally, to my mind, the most important insights in recent decades have come from two independent sources; an Austrian-German philosopher and a South African psychiatrist. Walter Johannes Stein was clairvoyant and during a “retrospective vision” on 27 June 1924 relived the last fateful hours of Almeida.33 Laurence Oliver, who may be described as a white sangoma (a traditional healer empowered by the ancestors), received an unexpected clairaudient message in 2003 in which Almeida’s fated end is told. Both point to an assassination in which the Viceroy was ritually executed by his own men.

Dr Stein, came to realise that he’d witnessed the murder of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida and describes the weapon used: “It was a strangely shaped ritual spear, the blade of which had a wavy outline. This spear struck him above the teeth of his upper jaw, killing him instantly.” His vision may have remained a mere footnote after his death in 1957, shared only among his confidants, had it not been for the survival of his diaries. His vision is all the more remarkable since he describes the weapon as a flamberge, a flame-bladed spear, the kind used by 16thC European mercenaries. Thus not a fire-hardened wooden assegai.34

Dr Stein, came to realise that he’d witnessed the murder of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida and describes the weapon used: “It was a strangely shaped ritual spear, the blade of which had a wavy outline. This spear struck him above the teeth of his upper jaw, killing him instantly.” His vision may have remained a mere footnote after his death in 1957, shared only among his confidants, had it not been for the survival of his diaries. His vision is all the more remarkable since he describes the weapon as a flamberge, a flame-bladed spear, the kind used by 16thC European mercenaries. Thus not a fire-hardened wooden assegai.34

The execution was thus performative, ritually cutting off Almeida’s tongue.

According to Dr Oliver: “Almeida was well aware of those factions within the Catholic cabals that were antagonistic toward his secret commission to reopen channels of esoteric intercourse between East and West, and that they sought to destroy not only his work but also his life. They had already succeeded in having him displaced from his position as Viceroy of the Indies, and so on his final return to Portugal, unsure of anyone else in whom to trust, he confided (…) that he was in peril of his life. It was thus at the Cape of Good Hope that the conspirators struck and carried out an order of execution, disguised as a prophecy of doom, that Almeida should not pass beyond the Cape. The ambush was carefully orchestrated as an altercation between the sailors and the irate natives. (…) The Viceroy was already dead, and his party wiped out, when the conspirators returned to seal their atrocity—ritually piercing Almeida through the throat with a lance of steel. Thus they silenced him forever”.35

According to Dr Oliver: “Almeida was well aware of those factions within the Catholic cabals that were antagonistic toward his secret commission to reopen channels of esoteric intercourse between East and West, and that they sought to destroy not only his work but also his life. They had already succeeded in having him displaced from his position as Viceroy of the Indies, and so on his final return to Portugal, unsure of anyone else in whom to trust, he confided (…) that he was in peril of his life. It was thus at the Cape of Good Hope that the conspirators struck and carried out an order of execution, disguised as a prophecy of doom, that Almeida should not pass beyond the Cape. The ambush was carefully orchestrated as an altercation between the sailors and the irate natives. (…) The Viceroy was already dead, and his party wiped out, when the conspirators returned to seal their atrocity—ritually piercing Almeida through the throat with a lance of steel. Thus they silenced him forever”.35

I hope this paper will speak on his behalf. I thank you for your patience and our conference organisers for this opportunity.

Nicolaas Vergunst