How are we to remember Nelson Mandela? Should it be as one of our most celebrated prisoners or, rather, as the first black president of South Africa? Should it be for his vision, his compassion, or for his strong will? Knot of Stone looks at his historical role as the “tree shaker”and the friends with whom he shared his past lives.

How are we to remember Nelson Mandela? Should it be as one of our most celebrated prisoners or, rather, as the first black president of South Africa? Should it be for his vision, his compassion, or for his strong will? Knot of Stone looks at his historical role as the “tree shaker”and the friends with whom he shared his past lives.

Among the various clairaudient messages published in Knot of Stone is one by the revolutionary pharaoh Akhnaton and the enlightened emperor Kublai Khan. They praise Mandela for his remarkable leadership during Egypt’s Eighteenth dynasty and China’s thirteenth century, and draw specific parallels to recent South African history. We highlight those parallels here.

“We would have that you hear the unfinished story of our time and its sequel in yours.” Akhnaton and Kublai Khan, KoS p.418

Akhnaton and Kublai Khan’s message was dictated unexpectedly over Easter 1996 and faithfully transcribed by the South African psychiatrist Dr Laurence Oliver. Cited in Knot of Stone, Chapter 94, the contents reflect neither the personal nor the political views of the clairaudient, the author or the publisher.

General Horemheb

According to the message, Nelson Mandela had been Akhnaton’s trusted military advisor in Amarna, c.1330BCE. He was born a commoner and rose to power as the commander-in-chief of Akhnaton’s army. He was known as General Horemheb:

“I, Akhnaton, would have you know that Horemheb is none other than your Nelson Mandela. Fourteen centuries before your present age, Horemheb was my military commander-in-chief and had warned me of the weakening political situation in my empire. Regrettably, I ignored his advice and forbade any military action. Withdrawn and out of touch with the populace, I concerned myself only with issues of religious revolution—the monotheist religion of Aton. For his worship I built a new capital, Akhetaton, ‘citadel of Aton’, and moved my court out of Thebes.”

Clairaudient message cited in KoS p.419

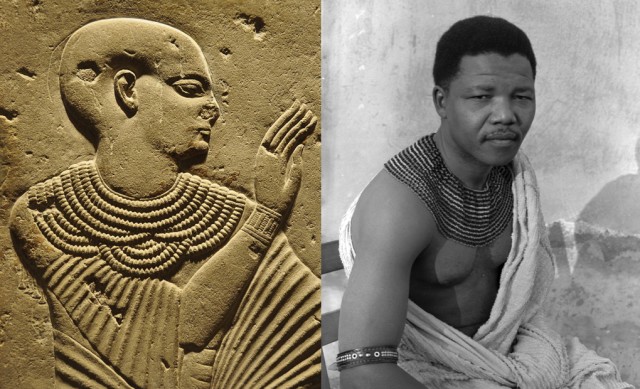

General Horemheb (left) c.1307BCE, from a tomb pillar at Saqqara; Nelson Mandela (right) c.1961, photo by Eli Weinberg. The photograph of Mandela was taken while he was in hiding, which is why a bedspread and not a traditional blanket was used to cover his left shoulder (a custom usually reserved for amaXhosa chiefs). Note the similar beaded neckpiece worn by Horemheb and Mandela.

General Horemheb (left) c.1307BCE, from a tomb pillar at Saqqara; Nelson Mandela (right) c.1961, photo by Eli Weinberg. The photograph of Mandela was taken while he was in hiding, which is why a bedspread and not a traditional blanket was used to cover his left shoulder (a custom usually reserved for amaXhosa chiefs). Note the similar beaded neckpiece worn by Horemheb and Mandela.

Akhnaton goes on to explain that Horemheb feared the continuing emigration of Egypt’s slave population—initiated by the Keeper of the Ark, Osiraes, also known as Moses—and that it would set off a Hebrew rebellion or invasion:

“Still, I refused to listen, preoccupied by my grandiose vision of a utopian church-state. Had it not been for the diplomatic initiatives of my minister of foreign affairs, Tutu, the eastern provinces may have seceded their independence. However, my political indifference was counterbalanced by Tutu’s tactful foreign policy, for he saved Egypt when I, alas, failed my people. It should be easy to guess that Tutu is the gracious and illustrious former archbishop, Desmond Tutu. Coincidently, my minister of art and culture was then Bek, the same as your Thabo Mbeki. He orchestrated under my direction a renaissance in art and architecture to express the religious revolution with which I was obsessed.” (KoS p.419)

“The celebrated Eighteenth dynasty came to an end under the rule of its military usurper Horemheb, which was to endure for twenty-seven years [1319-1292BCE]. It is in consequence of this that, in your era, he would endure imprisonment for another twenty-seven years [1962-1990], and so become the liberator of his oppressed people.” (KoS p.420)

Mandela’s given name, Rolihlahla, literally means “tree shaker” or “trouble maker”. Both Horemheb and Mandela shook their nation and took power through popular uprisings. Both set about transforming internal power structures and curbing abuses by the state. Both appointed new judges, re-established order and ruled a divided people (Horemheb over Upper and Lower Egypt, Mandela over White and Black South Africans). Both men initiated a culture of reconciliation. Curiously, each had two tombs prepared for them. Horemheb chose the necropolis of Saqqara at Memphis but was, instead, buried in the Valley of the Kings on the opposite side of the Nile. Mandela, as per his request, will be buried in the rural village of Qunu, twenty kilometres from where a second family tomb had been prepared for him.

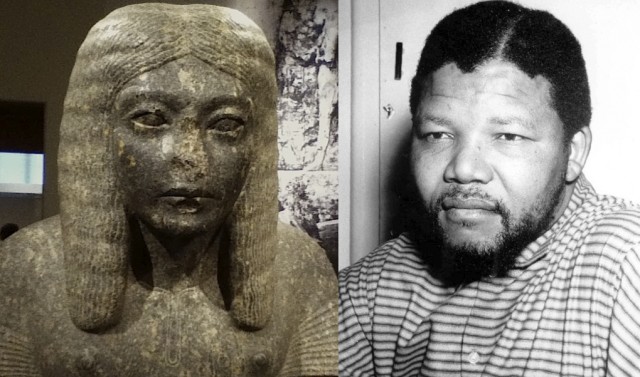

A scribe and a lawyer, General Horemheb (left) and Nelson Mandela (right). The photograph of Mandela was taken while he was on the run and staying in Wolfie Kodesh’s flat in Johannesburg, late 1961. Courtesy BBC. The statue of Horemheb dates from the 2ndC BCE and resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

A scribe and a lawyer, General Horemheb (left) and Nelson Mandela (right). The photograph of Mandela was taken while he was on the run and staying in Wolfie Kodesh’s flat in Johannesburg, late 1961. Courtesy BBC. The statue of Horemheb dates from the 2ndC BCE and resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Akhnaton also speaks about his tragic relationship to Nefertiti, chief consort, and his love for Tutankhamun, a son by another woman:

“My queen-wife, a foreign princess from the kingdom of Mitanni in the Tigris Valley, was called Nefertiti on account of her beauty. Her name means “beautiful woman” and she had been chosen as a new wife for my father, but their marriage was never consummated due to his ill-health. She is known today as Winifred, or simply Winnie, the former wife of Nelson Mandela.” (KoS p.420)

“I must digress to my unfortunate marriage again. Unbeknown to official history, I had a son by a beloved mistress Hareth, who was also my court singer. The child was called Tutankhaton, destined to rule as Tutankhamun. Nefertiti was exceedingly jealous, fearing she would be deposed as queen-wife in favour of the child’s mother. She became disloyal and treacherous, abducting Tutankhaton and taking him to Thebes. Here he was raised as a royal priest of Amen-Ra, like Osiraes [Moses] before him, so when the time came he would be presented as my successor, reclaiming their position as the state religion. Hence I am called the Heretic Pharaoh.” (KoS p.420)

The iconic bust of Nefertiti (left) by Thutmose, 1345BCE, from the sculptors workshop in Armana, Egypt, now in the Neues Museum, Berlin; and a portrait of Winnie Mandela (right) from 1975. Photograph courtesy Avusa. The reputations of both women were marred by allegations of abduction involving young boys.

The iconic bust of Nefertiti (left) by Thutmose, 1345BCE, from the sculptors workshop in Armana, Egypt, now in the Neues Museum, Berlin; and a portrait of Winnie Mandela (right) from 1975. Photograph courtesy Avusa. The reputations of both women were marred by allegations of abduction involving young boys.

Akhnaton relates how Tutankhaton’s mother, Hareth, was heartbroken by the loss of their son and subsequently drowned herself in the Nile. He says his own heart broke and he never smiled again. As the years passed his health began to fail slowly, then rapidly, so that he knew he was dying from grief and disillusionment:

“Shortly after this I, Akhnaton, died in despair. Smenkhare, my younger brother, bravely ascended the throne and defended my capital against the onslaught unleashed by the Amenite priesthood in Thebes. But the regime now seized its chance to regain supremacy in Egypt. I would that you know who Smenkhare was. He returned as General JC Smuts, twice South Africa’s prime minister, and similarly failed to stave off the ominous rise to power of a new regime—Afrikaner Nationalism.” (KoS p.421)

Approaching the end of his message, Akhnaton explains that his ministers and court officials, some ever loyal to him, returned as the black leadership of South Africa while, on the other hand, the priests of Amen-Ra became the leaders of the old white regime. Here are some examples: Sebekhotep, high priest of the Amenite crocodile-god, became state president PW Botha during the Apartheid era. Mahu, chief-of-police, returned as Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party. Akhnaton’s court secretary, Hani, was none other than Chris Hani, chief-of-staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s former military wing. Maya, Akhnaton’s chief administrator, returned as Roelf Meyer, chief government negotiator who, together with Cyril Ramaphosa of the ANC, paved the way for the country’s first democratic elections in 1994. “Karma,” the message adds, “has a way of turning events around to maintain a balance in the world.” Perhaps more pertinent here—as South Africa enters a new political phase—is the fact that Horemheb was succeeded by his trusted second-in-command, Ramses, first pharaoh of the Nineteenth dynasty. Ramses is today reincarnate as Cyril Ramaphosa and may, who knows, still become president of South Africa in 2017. (KoS pp.425-426)

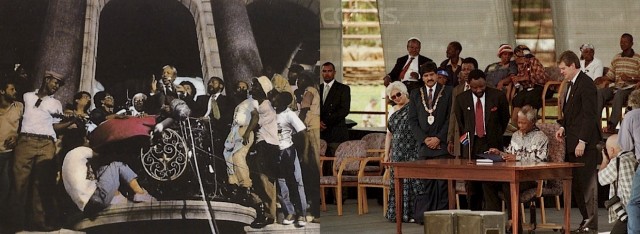

Two defining moments: First, Cyril Ramaphosa (left, wearing a green tie and holding the mike) watches Nelson Mandela deliver his first speech in public after his release from prison in 1991. Photograph by Chris Ledochowski. Second, Cyril Ramaphosa (right, now wearing a red tie) watches Nelson Mandela sign the new Constitution in 1996. Photograph by Charles O’Rear. These moments were the culmination of pivotal talks, both private and partisan, that set South Africa’s history on a new course.

Two defining moments: First, Cyril Ramaphosa (left, wearing a green tie and holding the mike) watches Nelson Mandela deliver his first speech in public after his release from prison in 1991. Photograph by Chris Ledochowski. Second, Cyril Ramaphosa (right, now wearing a red tie) watches Nelson Mandela sign the new Constitution in 1996. Photograph by Charles O’Rear. These moments were the culmination of pivotal talks, both private and partisan, that set South Africa’s history on a new course.

Helen Suzman (right) visits Nelson Mandela at his Soweto home in 1990, following his release earlier that year. For more than a decade, Suzman was the only MP to openly condemn the whites-only Apartheid regime. Photograph by John Parkin. President Jacob Zuma (right) celebrates Nelson Mandela’s 91st birthday at his home in Houghton on 18 July 2009. Photograph courtesy of the BBC.

Helen Suzman (right) visits Nelson Mandela at his Soweto home in 1990, following his release earlier that year. For more than a decade, Suzman was the only MP to openly condemn the whites-only Apartheid regime. Photograph by John Parkin. President Jacob Zuma (right) celebrates Nelson Mandela’s 91st birthday at his home in Houghton on 18 July 2009. Photograph courtesy of the BBC.

As for the women, Akhnaton admits that then, as now, men overshadowed women, regrettably. “But there was one woman who could have ruled Egypt better than any man, had she been given the chance. She was my dear and revered mother, Queen Ti, who returned as Helen Suzman.” (KoS p.421)

Lastly what about Jacob Zuma? It seems he was an Amenite priest called Ahmose or Ahmes and partisan to Nefertiti’s plot to install the abducted Tutankhaton as a puppet pharaoh. With their success he became vizier of the South, at Thebes, and is remembered as Usermontu. What’s striking about this parallel, is that Ramases was the vizier of the North (Pa-Ramose) and played a counterbalancing role then too. It will be interesting to see what happens between Zuma and Ramaphosa over the next few years. (KoS p.426)

Akhnaton concludes his message with the following exhortation:

“It matters not who was who, who did what, or who was right and who wrong. What matters are the lessons to be learnt from one another. In the politics of your day, there is no one who is right and all others wrong. There are but those who seek to serve their own self-interest and those who consider the good of all. You judge which way is best. Be wise and broad-minded in your judgements; gentle and generous in all your doings. To my former ministers I say: may you remember who you are and heed the lessons taught by my life as Akhnaton. May you fulfil the best of my ideals and triumph over the worst of my tragedies. There is no cause whatsoever that justifies enmity against one another, no ideal worth the exaction of another, for you must live up to your ideals with inner fortitude and not, no, not with outer hostility. This is the lesson South Africans must learn and teach the world: that ideals cannot be divorced from the people they serve but must grow in their hearts and minds, not through imposition, but through nurture. Let my people grow. I am Akhnaton.” (KoS pp.421-422)

Pharaoh Amenophis IV Akhnaton (left) 1375-1358BCE, fragment from a monumental statue in Karnak, Egypt. Courtesy of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Kublai Khan (right) 1215-1294, as painted by the court astronomer Anige shortly after the emperor’s death. Courtesy of the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan.

Pharaoh Amenophis IV Akhnaton (left) 1375-1358BCE, fragment from a monumental statue in Karnak, Egypt. Courtesy of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Kublai Khan (right) 1215-1294, as painted by the court astronomer Anige shortly after the emperor’s death. Courtesy of the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan.

Mongka Khan

In the second part of the passage Kublai Khan speaks about his relationship to Nelson Mandela in thirteenth-century China:

“I who speak to you am Kublai Khan, the enlightened overlord of a cultural renaissance dedicated to the advancement of religion, art and knowledge. My history must speak for itself, for it is not why I come to you. I would speak of my brothers Mongka, Hulagu and Boka, who are reincarnate among you today as Nelson Mandela, Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Thabo Mbeki, respectively. We four were then heirs of the monstrous Temüjin, our grandfather, known to you as the notorious Genghis Khan. My beloved spiritual brother, Akhnaton, has already informed you of their ancient incarnations in Egypt’s Eighteenth dynasty, and I would show you now how their thirteenth-century incarnations in Mongolia shaped their political roles in your world today. I do so neither to glorify nor vilify them, but to illustrate what lessons life teaches us through karma.” (KoS pp. 422-423)

“Genghis Khan bequeathed an empire unparalleled in the history of the world. Established through merciless massacres, his realm embraced almost all Asia and was to expand further east and west under his descendents. After our grandfather’s death, his four sons contested the succession… Batu Khan, who extended the Russian conquests into Eastern Europe, favoured the eldest Mongka for Grand Khanate. This may seem ironic, if you recall that Batu was PW Botha, the president who perpetuated the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela on Robben Island. Mongka’s own military triumph in the ensuing civil war made him, before all, the undisputed Great Khan. The deposed princes were banished while the ex-regent’s mother, Oghul, was executed for her sorcery and treachery. She had striven sorely and bitterly against his ascension. I leave it to your discretion to recognise Oghul in her present-day incarnation, in the light of Akhnaton’s disclosure.” (KoS p.422)

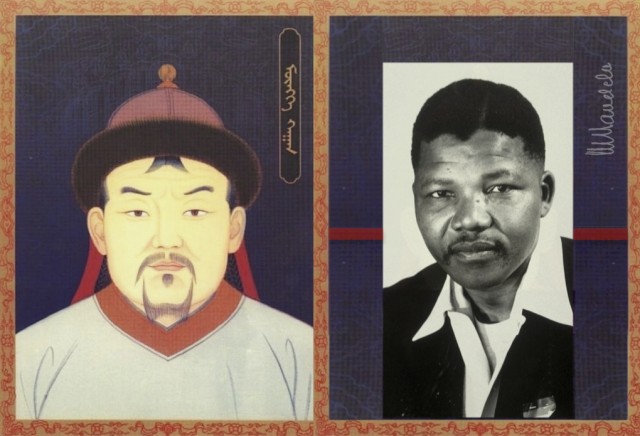

The emperor and a president, Mongka Khan (1209-1259) and Nelson Mandela (1918-2013). Mongka was the first Great Khan from the Toluid line and made significant reforms to transform the Mongol Empire, earning him the title of Supreme Khan and King of Kings. Likewise, Mandela has been hailed the President of Presidents. The 13thC painting of Mongka shows a cartouche with his name in traditional Mongolian script, while Mandela’s signature appears alongside the photograph of him from c.1957.

The emperor and a president, Mongka Khan (1209-1259) and Nelson Mandela (1918-2013). Mongka was the first Great Khan from the Toluid line and made significant reforms to transform the Mongol Empire, earning him the title of Supreme Khan and King of Kings. Likewise, Mandela has been hailed the President of Presidents. The 13thC painting of Mongka shows a cartouche with his name in traditional Mongolian script, while Mandela’s signature appears alongside the photograph of him from c.1957.

Kublai Khan goes on to explain how Mongka became the Great Khan and his court at Karakorum the diplomatic centre of the world, receiving embassies from all over Asia and Europe. Mongka, like Mandela six centuries later, believed law and order was the way to create political conditions necessary to unite all peoples under a common welfare of peace and prosperity. And like Mandela, once again, he practised no racial or religious discrimination:

“Mongka believed in one God, but in no particular form of worship. He attended religious ceremonies of all the great faiths—Buddhist, Christian and Muslim equally—and religious freedom was well tolerated by him. But he never could tolerate dissension and was ruthless with those who pitted themselves against him.” (KoS p.424)

While Mogka held court, his brothers re-expanded the Mongol empire. Batu (Botha) used his Golden Horde to occupy Russia and eastern Europe; Hulagu (Buthelezi) conquered Persia; and Kublai Khan established the Yüan Dynasty. Kublai Khan is reincarnate today as Tenzin Gyatso, beter known as His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Please see our related post on the karmic connections between the Dalai Lama, Tutu and Mandela.

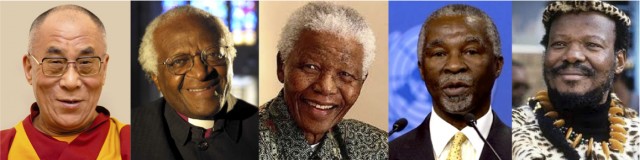

The Dalai Lama (Tenzin Gyatso), Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki and Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

The Dalai Lama (Tenzin Gyatso), Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki and Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk, Nobel Peace Laureates, in 1993. Both men took an extraordinary leap of faith, together, thus changing the course of South Africa’s history forever. This joint award acknowledged their shared roles in the country’s historic path to reconciliation. Sadly, the road is far less travelled today.

Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk, Nobel Peace Laureates, in 1993. Both men took an extraordinary leap of faith, together, thus changing the course of South Africa’s history forever. This joint award acknowledged their shared roles in the country’s historic path to reconciliation. Sadly, the road is far less travelled today.

As for Zuma, finally, we should say that he reappeared in Kublai’s court as Ahmad Uzma who, judging by his name, appears to have come from what is now Uzbekistan. He rose to the position of finance minister, taking advantage of his master’s misplaced trust and the distractions of civil war. He was reputedly a corrupt court official and, too, renowned for his many wives. Though accused of murder, the Grand Khan sidelined all attempts to impeach Uzma (Zuma) and kept him at court. Despite this Uzma’s abuses of power did not stop and, like Zuma again, he had to face charges for capitalizing on arms-deals.

Cyril Ramaphosa and Jacob Zuma at the African National Congress conference in Mangaung on 18 December 2012. Following a dramatic election battle, Zuma swept to victory as president of the ANC and secured a second term as party leader, while outsider Ramaphosa was elected as his deputy. Their bond goes back to ancient Egypt when both served as Armenite priests at Thebes. Photograph courtesy of Ouest France.

Cyril Ramaphosa and Jacob Zuma at the African National Congress conference in Mangaung on 18 December 2012. Following a dramatic election battle, Zuma swept to victory as president of the ANC and secured a second term as party leader, while outsider Ramaphosa was elected as his deputy. Their bond goes back to ancient Egypt when both served as Armenite priests at Thebes. Photograph courtesy of Ouest France.

With this, Kublai Khan too concludes:

“From my spirit realm, I advocate the renaissance in South Africa. I know all too well the difficulties of trying to serve spiritual ideals in a world of political contention and religious strife. I also know that it can be done, and done well. To my three brothers in this life, and to my spiritual brothers and sisters of the eternal past, I say: help one another. Help each other to live up to your highest ideals as human beings. True humanity lies not in enmity and conflict, but in tolerance and goodwill. I am Kublai Khan, the Dalai Lama of your time.” (KoS p.425)

South Africa is heir to the karma of ancient Egypt and medieval China—and its racial-political dilemmas stem from that past. Laurence Oliver, KoS p.432

Nelson Mandela

The world will soon lose a great man, a man of noble actions and kind deeds. But the world will also have gained from his lessons of equality, justice and gentleness. It is a world in which Mandela has demonstrated that racism makes no sense when we incarnate into different bloodlines all the time. Moreover, it is a world in which love triumphs over hate: “No one is born hating another person because of the colour of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.” (Autobiography, 1995)

As Mandela’s given name suggests, let’s remember Rolihlahla as a true Tree Shaker.

Nicolaas Vergunst