Cape Town, 1 March 2013—the Quarterly Bulletin of the National Library (QBNL) lists Knot of Stone as one of South Africa’s “exciting new publications”. Editor, author and professor of African studies and Cape slavery Robert Shell appraises the book’s appearance against the 500th+ anniversary of the Almeida-Khoena massacre.

Cape Town, 1 March 2013—the Quarterly Bulletin of the National Library (QBNL) lists Knot of Stone as one of South Africa’s “exciting new publications”. Editor, author and professor of African studies and Cape slavery Robert Shell appraises the book’s appearance against the 500th+ anniversary of the Almeida-Khoena massacre.

Nicolaas Vergunst’s Knot of Stone deals not only with the country’s first recorded battle—and its knock-on effect across two oceans—but is itself a timeous publication for anyone interested in South Africa’s place in the world today. Its appearance marks the fifth centenary of the event.

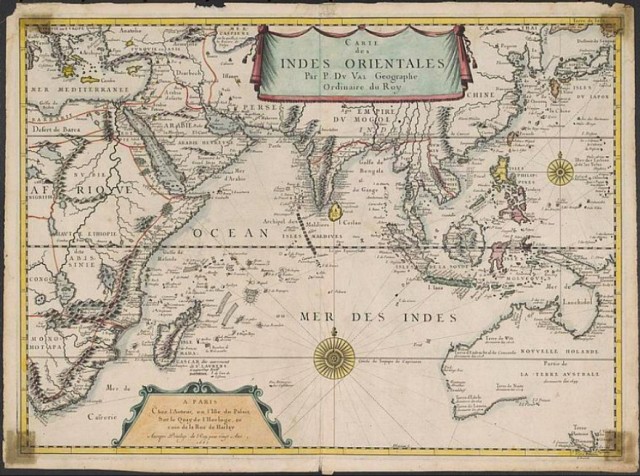

As the first Viceroy of Portuguese India, Francisco d’Almeida (c.1450–1510) led Europe’s entry into the Asian environment, re-establishing a direct link between the East and West after the fall of Constantinople. As Admiral he secured the carreira da Índia (India Passage) which severed Muslim control of traditional trade routes to and from the Mediterranean. As Viceroy, he governed the Estado da Índia (State of India) that embraced the world’s oldest blend of Christianity in East Africa and South Asia, a blend that assimilated elements of Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism and Judaism. Almeida not only wished to expand Portugal’s overseas empire in the Indian Ocean but also strove, Vergunst believes, to prepare cosmopolitan societies for the advent of universal values.1

On leaving India the sorcerers (seers) warned Almeida that he would not pass beyond the Cape of Good Hope—it being the western limit of his realm. The women passed him in a skiff as he boarded his ship, the Garça, which lay ready for immediate departure. Their prediction prompted him to rewrite his last will and testament over the next few weeks. Later, when rounding the Cape of Good Hope in fair weather, he said to his men: “Now, may God be praised, the witches of Cochin are liars.” A few leagues farther, after coming ashore, he was slain at the watering place previously used by António de Saldanha, one of his captains, and for whom it was named “Aguada de Saldanha.” Locals called the place “Camissa”. Here he and his men spent the next ten days replenishing their supplies, repairing the boats, and befriending the herders from whom they also hoped to obtain fresh meat.

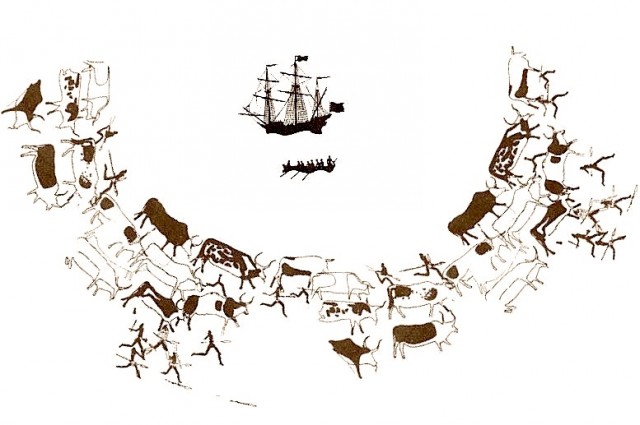

The massacre of Francisco d’Almeida at the Cape of Good Hope, 1510. From Pieter van der Aa’s Nauwkeurige versameling der gedenkwaardigste zee- en landreysen naar Oost- en West-Indië…, Leiden, 1707.

The massacre of Francisco d’Almeida at the Cape of Good Hope, 1510. From Pieter van der Aa’s Nauwkeurige versameling der gedenkwaardigste zee- en landreysen naar Oost- en West-Indië…, Leiden, 1707.

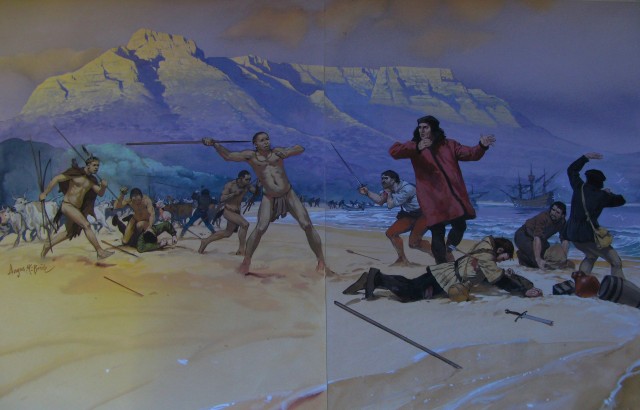

According to the historical records, the Khoe (Khoena or Quena) came down to the beach when the Portuguese dropped anchor in Table Bay—probably near the V&A Waterfront today. During the next few days, while the sailors filled their water caskets and collected firewood, the bravest herders befriended the interlopers, becoming familiar with the ways of the “Strange Ones” from across the Great Water. After a week, Almeida yielded to requests that a few of his men visit a nearby village, most likely that of a Goringhaiqua clan near present day Mowbray/Rondebosch, to see if they could fetch some cattle or sheep. It was there that the alleged quarrel began, leading to Almeida’s demise on 1 March 1510. The Cape Khoe kept large herds of trained war-oxen which, when driven together, formed a formidable battering ram and self-protecting shield. Early European travel writers observed how the Khoe darted in and out whistling instructions as they drove their herd into a stampede. Unable to withstand the onslaught, Almeida’s party fell back to the beach where, once hemmed in between the dunes and rising tide, they found themselves overwhelmed by the Khoe. Here Almeida and those loyal to him met their end under a hail of fire-hardened spears and slingshot-stones.2

The Cape Khoe kept large herds of trained war-oxen which, when driven together, formed a formidable battering ram and self-protecting shield. Early European travel writers observed how the Khoe darted in and out whistling instructions as they drove their herd into a stampede. Unable to withstand the onslaught, Almeida’s party fell back to the beach where, once hemmed in between the dunes and rising tide, they found themselves overwhelmed by the Khoe. Here Almeida and those loyal to him met their end under a hail of fire-hardened spears and slingshot-stones.2

The massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, 1510’ by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy of the Castle Military Museum, Cape Town.

The massacre of Viceroy Francisco d’Almeida, 1510’ by Angus McBride, 1984. Courtesy of the Castle Military Museum, Cape Town.

Vergunst points out that the Quarterly Bulletin is itself “a seminal reference since the circumstances and location of the Almeida-Khoena conflict were first published herein during 19883 and 19904.” He suggests that the articles may have been included to counter the 1988 landmark celebrations of white/apartheid/colonial history in South Africa and, furthermore, that the debate twenty-five years ago turned around whether Hout Bay or Table Bay were the appropriate sites for a Portuguese landing? Vergunst adds that “the Quarterly Bulletin provided a crucial account of the skirmish and its probable siting on the shores of Table Bay (as opposed to Saldanha or Hout Bay, then also in contention). Over the last two decades, c.1990-2010, the debate has shifted to interpretations of the event by professors of literary studies, local historians and First Peoples’ spokesmen. The interventions made by David Johnson, Patric Tariq Mellet and Ron Martin need no elaboration here, except to say that their analysis, politicisation and radicalisation gave the event the sharp edge it has today.”

Like a double-edged sword, says Vergunst, the blades of the academics and activists mentioned above cut both ways: “The discourse now serves ulterior motives; such as promoting indigenous memory, cultural identities and land restitution claims. The event itself has become a symbol for the first armed struggle (and first victory) against a racist oppressor.” He cites Ron Martin as saying that the killing of Almeida was “our finest hour and gives us pride of place in modern history.”5 While Vergunst does not contest the issue of land and language recognition in South Africa, he does argue that “political empowerment should not jeopardise genuine historical research, nor should we rewrite the past to suit local prerogatives. It is of minor interest to me who drew the first weapon or wielded the final blow, or who were the true victors and who the fated losers, as I have no need to apportion blame.” As shown in Knot of Stone, Almeida’s executioners wanted to prevent him from reopening philosophical/esoteric intercourse between the Orient and Occident: “Any interpretation that ignores or denies this,” he concludes, “fails to see the transoceanic significance behind Almeida’s death at this southern portal between East and West.”

Robert Shell

Carte des Indes Orientales by Pierre Du Val, Géographe Ordinaire du Roy, Paris, 1677.

Carte des Indes Orientales by Pierre Du Val, Géographe Ordinaire du Roy, Paris, 1677.