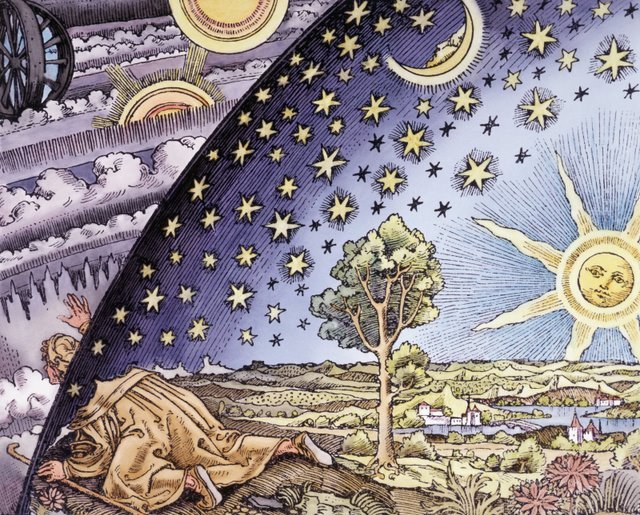

A sixteenth-century style woodcut thought to be made for the French astronomer Camille Flammarion, 1888.

A sixteenth-century style woodcut thought to be made for the French astronomer Camille Flammarion, 1888.

What does a writer do when the limits of the historical record have been reached: turn back or look around?

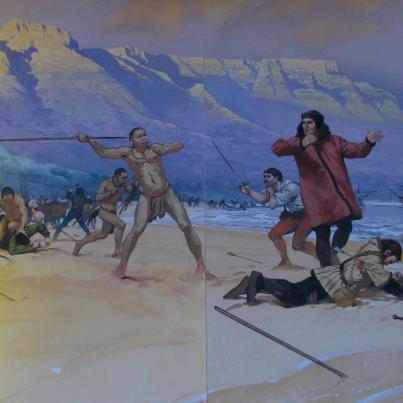

As Professor Malyn Newitt once said: “The history of Portuguese expansion is at once very well known and hardly known at all.” Today I wish to say with him that the history of South Africa’s first battle is at once very well known and yet hardly known at all.

In fact the official account of Almeida’s murder is full of gaps and inconsistencies, repeated by successive generations, many of whom did so a century or two after his death—that is, long after witnesses could question the records. Moreover, no one ever stopped to challenge it either, at least not officially. Nor did anyone ask if there had been foul play; such as a mutiny or an assassination?

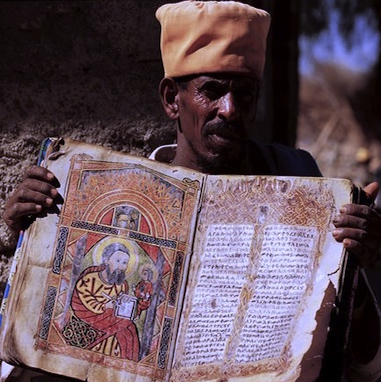

Once I started writing Knot of Stone, several new or alternative sources came my way; such as legends, dreams, visions and oral histories. This may sound strange to a the Western ear, but having come from museums steeped in various African traditions, this was not at all odd for me. I am comfortable working with those for whom legends, rituals and sangomas play a significant role. For me, ancestral memory should be spoken and heard. It is often the only source we still have left. As the African proverb says: “When an old man dies, a library is lost.”

Once I started writing Knot of Stone, several new or alternative sources came my way; such as legends, dreams, visions and oral histories. This may sound strange to a the Western ear, but having come from museums steeped in various African traditions, this was not at all odd for me. I am comfortable working with those for whom legends, rituals and sangomas play a significant role. For me, ancestral memory should be spoken and heard. It is often the only source we still have left. As the African proverb says: “When an old man dies, a library is lost.”

I know oral/oracular sources are difficult to accept, especially in western societies where these have waned in favour of empirical knowledge, making inclusion of the “Ancestral Voice” both challenging and thought provoking. It is for this reason that I chose the novel form over that of the travel journal, biography or monograph.

With its unique or peculiar mix of sources, Knot of Stone proposes that Almeida’s death was not the result of a local skirmish alone—but also caused by political intrigues back home in Europe, thus binding developments in Southern Africa to Western Europe. Furthermore, the assassination attempt on Almeida and the political leadership since Nelson Mandela are, ultimately, two ends of the same knot in South African history. Now is not the time for this, but see Chapter 94 (pp.418-427).

With its unique or peculiar mix of sources, Knot of Stone proposes that Almeida’s death was not the result of a local skirmish alone—but also caused by political intrigues back home in Europe, thus binding developments in Southern Africa to Western Europe. Furthermore, the assassination attempt on Almeida and the political leadership since Nelson Mandela are, ultimately, two ends of the same knot in South African history. Now is not the time for this, but see Chapter 94 (pp.418-427).

Writing this book called upon me to challenge myself and, moreover, to test my ideas and beliefs with rigour. I have no doubt that it will, in turn, challenge others to be receptive to reading and inscribing events in both new and alternative ways.

![]() This introduction was presented at a luncheon held to launch Knot of Stone in London on 5 September 2011.

This introduction was presented at a luncheon held to launch Knot of Stone in London on 5 September 2011.

Nicolaas Vergunst

24 September, Heritage Day, a national day set aside to commemorate former heroes of the liberation struggle in South Africa and a highpoint in the ANC’s 2012 centenary celebrations. However, this is not a day shared with equal enthusiasm since it fails to address the collective history of all South Africans. If we are to celebrate our heroes, from both before and after apartheid, then I suggest we regard them as the successors of an age-old tradition: According to Bantu belief the ancestors return to live again through their descendants and, moreover, are only reborn if the living remember them. We are thus dynamically linked to our ancestors through birth, death and the life to which we all return. Karmically speaking, we are the inheritors of this ancestral quest for justice—one in which Steve Biko and Nelson Mandela also played their part—and today’s political leaders have to do so too!

Forget about Heritage Day this year, it’s time for the new smartphone app.